Decline of Mourning

The decline and disappearance of the mourning industry does not have one simple answer. It is a mix of cultural changes, mass production, a shift towards new wealth and the new world governing style, combined with female empowerment and what the definition of the family meant. The 1861-1901 period had been one of rapid growth for the British Empire, but the focus was on the connection of cultures in an empire where the sun never set.

Permeation of ideas, style and materials throughout the world enabled artists to be highly individualised outside of firms and production houses. Lower cost and high investment from new wealth let artists contradict the very formal style that was imposed from a monarch who did not exit her mourning after the death of Albert, making Court style mourning-influenced. Static Western culture looks to our communities for inspiration when the interest and access to new affectations doesn’t change. By the mass production of modern culture, the allowance for new fashion comes to the very forefront of our minds and what we see, we covet and can own.

America was driving much of the change in its access to new wealth through the oil mining industry. From this, American investment towards European artists in order to create styles of fashion that were individual, rather than following a global trend or aristocratical change, made great advances in modern fashion. This was helped by fashion magazines which could express the investment of new wealth into fashionable artists upon the many cultures that these magazines reached.

The further a society gets from physical production, the further removed they become from its reality. Many of the ingredients in a regular cuisine and its preparation are lost to the person in the restaurant who consumes it, the fabric in a garment and its construction are continents away from the person who wears it. Appreciation for the essentials of living are taken away from a highly produced society. Mourning is no different. Of course grief remains as a fundamental reality of our beings, but the interment of the body and the rituals built around it are beyond culturally specific. Multiculturalism in a community focus the methods of grieving to the household and the family unit. Western governments rarely mandate any formality around mourning, unless there is a state funeral for a monarch or popular figure, hence there’s no requirement to wear black, create jewellery or be in an imposed state of mourning. It’s a choice that a person needs to make, beyond any structure. There are remnants of 19th century mourning within Western culture that remain, particularly in the burial and symbols surrounding death.

Another factor that led to the decline in the formality of mourning was the high mortality rate of the First World War. Formality around what was the established mourning periods for fashion had been massively impacted with the entire period of 1914-1918 being mass period of human attrition. It impacted both Protestant and Catholic based societies, which have their own values beyond the basic cultural regulations of mourning, to create a mass period of grief for those who were at home and discovered the news of a loved one’s death.

“The streets were full of women dressed in black; the churches were crowded all day long… for the first time in a century, the Parisienne was almost indifferent to what she wore.” – Lady Duff Gordon, Discretions and Indiscretions, 1932

The lines of regulation are blurred when there is a complete period of mourning over the course of the mandated times. Families perished under the Great War and specific times of wearing mandated stages of mourning overlapped to create a generalisation of what it was to be in mourning itself. The matriarch of the family representing the family itself in society was facing a rebellion since the 1880s. While general fashion had adapted since the 1860s, notably losing the crinoline, the imposition of being in mourning entertained a younger generation to rebel against the stoic ways by turning around their veils. By the time of the Great War, a conscious move towards the empowered individual was resonating through the Edwardian period.

WWI caused the harsh reality of mortality, and how to deal with grief in a massively cross-cultural way, something which could not be avoided or simply an affectation. Fashion needed to enter mourning; the artists and fashion houses that gained so much importance via the new wealth that had fed it in the 1890s onwards would be considered a negative display of wealth and design in a society that could not appreciate it.

“This year not one solitary costume was remarkable. Where is there not a person who is suffering family and financial losses that make display and frivolous expense seem folly…” – London Illustrated News

So it is through the lack of a fashion industry that mourning regulation, and the appeal of what it was to be in mourning, decline. Mourning is a burden and a difficult situation that is part of day to day life, when every member of the family unit is under threat of death. Reviving this in a way that goes beyond the personal, and told to do so as such by a government, is far more affecting to the pomp that surrounds it. Death was present, so the individual needed to deal with that. It may be through a closer connection to a god or the harsher aspect of dealing with the fact of interment, but Europe faced this over a long period on a day to day basis.

“Never has the code of mourning been less strictly applied, than in these days of anguish.” – Mode illustrée, 1916

From this move away from formalised mourning becomes a generation which would carry on these practises and adhere to less formal mourning regulation. This is the basis for modern society today As the requirements became less rigid and the counteraction to what generation had done before, even the concept of a regulated mourning period seems antiquated.

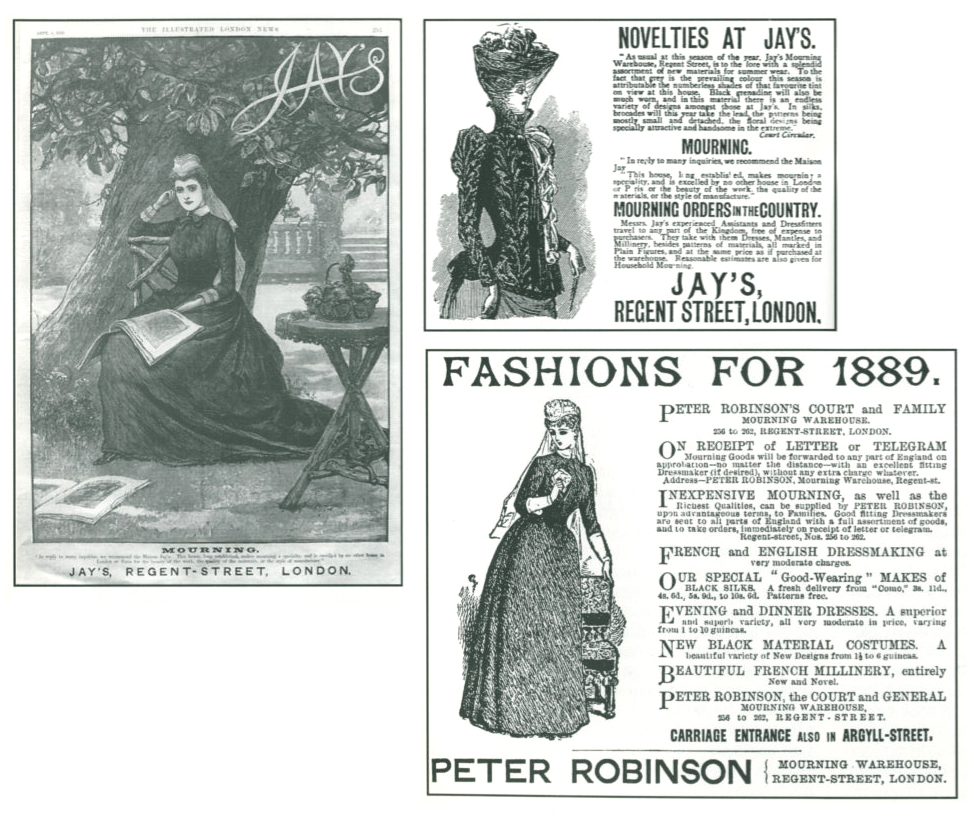

Crape was the primary material used in mourning fashion from the 19th century, being non-reflective and symbolic of the first stage of mourning under court mandate. Widows had to wait one year and six weeks, with the first six months in black wool. Lord Chamberlain and Earl Marshall both ordered shorter periods of mourning in France and England respectively. By the 1880s in Britain, twelve weeks of mourning were ordered by the death of a king or queen, six weeks after the death of a son or daughter of the sovereign, three weeks for the monarch’s brother or sister, two weeks for royal nephews, uncles, nieces or aunts and ten days for the first cousins of the royal family. Foreign sovereigns were mourned for three weeks and their relatives for a shorter time. Mourning was divided up into First, Second and Court mourning.

It was on the 7th of November, 1817 upon the death of Princess Charlotte that Lord Chamberlain ordered official Court mourning: ‘the Ladies to wear black bombazines, plain muslins or long lawn crape hoods, shammy shoes and gloves and crape fans. The Gentlemen to wear black cloth without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers [white cuffs] shammy shoes and gloves, crape hatbands and black swords and buckles.’ For undress wear, dark grey frock coats were permissible. The Second stage was decreed two months later, with the allowance of black silk fabric, fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black shoes, fans and tippets, white necklaces and earrings, grey or white lusterings, damasks or tabbies and lightweight silks for undress wear. Men’s dress was unchanged. The third stage allowed women to wear black silk and velvet, coloured buttons, fans and tippets and plain white, silver or gold combination coloured stuff with black ribbons. Men could wear white, gold or silver brocaded waistcoats with black suits. The rules set by Lord Chamberlain crossed Europe, the United States (from the 1860s / 70s) and colonial territories, but Court mourning was longer than General mourning. General mourning was growing in popularity due to the accessibility of mourning costume and the cost.

Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this Industrial Revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels.

Machine power was the proponent of having mourning fashion be affordable and attainable. George Courtauld, in conjunction with Joseph Wilson, converted a flour mill in Braintree, Essex, to manufacture silk yarns and crape gauzes. This was established in 1809-1815, with silk-throwing, steam-driven machines being tested in 1827 leading to 2,000 local workers being employed and notorious for a fine coloured silk known as ‘aerophane’. Between 1835 to 1885, profit grew from £40,000 to £450,000. Courtaulds employed a great number of women in the Finishing Department of the process and was notorious for its labour force, which also employed children against the 1833 Factory Act.

Their decline came in 1886, with the 1880-82 period of fabric being ordered at 46,000 packets of fabric to 30,000 in 1892-94. This is a steep decline that relates to the end of the mourning industry and its fashion. The entire mourning industry was in a decline from the mid 1880s – an entire generation of a culture with once fluid fashion changes had been living under the shadow of mainstream mourning culture from 1861, due mostly to a queen perpetually in mourning. By 1887, for Victoria’s golden jubilee, she had started to lessen the mourning restrictions and re-emerge in public, but there was even a cultural shift that had begun with women who lived as the centre of household mourning starting to rebel against the older ways.

On the continent, however, much of the exports of Courtaulds’ sales were to France, as in 1899, more packets of crape, known as ‘Crepe Anglais’, were sold than had been previously seen. Courtaulds offered a softer crape, which was popular, rather than the stiffer fabrics, and was advertised as such. By 1921, ‘Latin Countries’ were the major exporter of crape, which speaks to the change in dominating mourning styles from the ecclesiastical to the fashionable. Being in popular fashion, mourning was challenged; not something that was mandated as it had been, particularly through the period of the First World War and its high mortality. The pomp surrounding mourning reduced to be personal. Mourning and its stages weren’t enforced and not an indictment on the family, so what a person felt was more allowable to be presented within society for mourning ritual. As to the crape and its exports, this was more popular in Catholic cultures, which still retain formality around public mourning.

Black crape remained at a cost of around £200,000 between 1913-1918 and saw a slight increase in 1919, but dissolved very quickly after this. Fashion magazines were the new focus of what was acceptable in mourning, not the Court, signalling the end of aristocratically led fashion. A widow was suggested to spend one year and six months mourning a husband. Gazette du bon ton outlined the new suggested mourning fashions in 1920. ‘Grand Deuil’ was the deepest mourning period, utilising wool and crape, ‘Petit Deuil’ was the second stage with black silk and taffeta with dull stones, while ordinary mourning was white crape with pearls and diamonds.

Style had remained largely consistent with little movement since the 1860s, though women’s clothing had lost the heavier crinolines, bold mourning jewels remained bold and prominent. This female paradigm shift had started to become an outward rebellion, with some women even wearing their veils backwards as an act of defiance. The Art Nouveau movement emerged as a breath of fresh air, with its opulent, organic, styles, using nature as its dominant motif, rather than retroactively mining the past for revival styles. Jet was not conducive to this new art movement and did not adapt. Black stones used as a material following this period in Art Deco were often onyx or glass, which became, and remains, popular to this day.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, those from the older generation still maintained many of the mourning rituals which they had grown up with. Even after the death of King George V in 1936, the Vogue suggested that people outside of Court “…in the interests of thousands who depend on catering, entertainment be leading a normal social life.” This is a major repealment of the Court mandates of the 19th century that standardised mourning to the highest degree.

From 1900, there was a significant split in jewellery styles. Court-worn jewels were still based around the Rococo Revival style and using highly privileged, material-based gems, such as diamonds. This was normal around European Courts and remained consistent from the 19th century. In Europe, the organic influence of Art Nouveau and its use of coloured gems and enamel became popular. The Arts and Crafts movement flourished in Britain as a response to mechanisation; bringing back a return to traditional crafts. This remained consistent up to the beginning of the First World War.

South African diamonds produced 90% of the world’s diamonds in 1890, with a slight interruption by the Boer War in 1899-1902. White gold and platinum were used to enhance the look of the diamond, leading this to become one of the most popular styles in fashion for the time. Its influence can be seen today, with ‘white’ jewellery being more popular than the silver influence of the 1880s simply because diamonds were enhanced by the white colouring of the metal and diamonds themselves were cheaper and more accessible.

‘Garland’ style jewellery was made popular by Cartier, which referenced Louis XVI style, featuring garlands of laurel leaves, lace patterns, ribbon bows and tassels. This style resonated throughout Europe and America, but only in high wealth. Art Deco had its origins in this style, with Boucheron, Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels all experimenting this style, but adding gems and exploring its development.

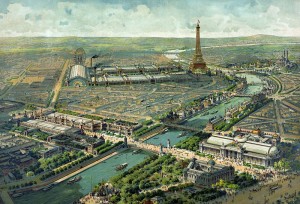

It was the financiers who made this development possible. At a time when new wealth could define new styles, going beyond the previously established family-based old money, Americans began to spend their money in Paris, leading to the rise in jewellery production houses and their proliferation. Tiffany & Co. developed by this money and presented their quality work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. Notably, their contribution to jewellery development was the Tiffany Setting in 1886; a diamond setting above a ring which lets in as much light as possible to the stone. René Lalique, whose influence to Art Nouveau is exponential, was awarded a Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition, leading to the popularity of delicate, organic styles in jewellery design and development. Methods, such as the Plique-à-jour enamel work (meaning ‘letting in the light’), were fundamental in how jewellery design was reacting to the previously consistent styles that had represented the late 19th century.

This is why the Paris Exhibition was so fundamental in disseminating new styles throughout mainstream culture. Wealth from America and driven by industry was empowering artists to go beyond the Court/aristocratic styles that hadn’t had the early 19th century monetary drive and lockets such as this ampersand piece could thrive. Look to the design of this piece; the Nouveau elements, from the organic curve to the floral outcrops.

With the high level of accessible and affordable travel in the early 20th century, there was a rise in sentimental tokens being produced in high quantities to be given to loved ones while travelling, or bringing home as a remembrance of the voyage. Combined with the new Romantic movement that looked towards the 18th and early 19th centuries, many jewels were reproduced to represent those that had come before.

Various levels of quality reflect these jewels, with new methods of production and transit leading to higher mobility between cultures for their global population. Establishing these production methods created standardised love token representations that are still relevant today. The Neoclassical representations of love and affection, in this case cupid with the bow and the cherubs, with the temples and different displays of the female, underpin modern jewellery based around sentimentality. Indeed, even cameos can be identified to their era by the contemporary hair and fashion styles. Here, we have a lady displaying her ankles and raising her skirt, with low-cut bustling and tied hair. The poorly defined floral elements flank her, but attention has been given to her costume’s lace.

Marcasite was a popular element of jewellery in the early 20th century, moving its interpretation from being a diamond substitute to becoming a popular element in its own right. You can see this used as the border of the piece. Surrounding this are faux pearls, with the damage to the north of the piece.

Identification can be an issue for many of the jewels produced during the early 20th century. With the Romantic period using many of the early 19th century elements of love and affection, so many pieces that would not seem in fashion were created during a time when emerging art forms, such as the Arts and Crafts / Art Nouveau development, dominate the perception of the time. Love and sentimentality didn’t change overnight since Queen Victoria’s death, but evolved with fashions that certainly did look more organically to the world around. This piece shows an adaption of the old and the new, but still tells a tale of love.

Mourning and sentimentality are cultural as much as they are personal. The ways in which death and love are represented have more to do with how a person wishes to represent their value system in public. Through the 20th century and its high cultural mobility, singular mourning and sentimental beliefs are cross-pollinated. With one of the few catalysts for a public display of love or grief being a message which is conveyed by the highest level of media. This influence for change by the media and its display of a tragic event or fashion can influence the lives of those who have access to that media. This can throw cultures into a dominate style or concurrent mindset on a broader scale than a traditional culture that has carried on its core system of beliefs since early-modern times.

Because of this, the symbols that were revived and those that remained through the late 19th century are the ones we identify with today as being the symbols for mourning and sentimentality. Those that had fallen behind, such as the use of hairwork, are approached with modern mindsets that may consider wearing hair to be morbid, whereas it was a fashionable material for its time.