Colonial Australian Sentimental Jewels

Opportunity is a natural aspect to human advancement. Circumstances that are created by governments and politics may be harmful to a culture or a regional territory. Colonisation was one of the most aggressive aspects in Western growth that the world had seen. Rapid transit, mapping and a desire to contest other countries for domination led to the annexing of cultures and the infestation of imposed culture globally. While this happened on a global scale from the early modern period, this is an element of human behaviour that has defined and created cultures since prehistory.

But it is opportunity which the people who have existed in these times of growth that is looked towards. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the allowance for a new life in a new territory became an option. Gone were the constraints of the village or city, now one could find a place to escape to and build a family in an area where the only chance for survival was the ability to grow and to build. To move from a culture that had its systems established through centuries of development to a new land of disparate cultures and form an identity within the space of decades is a remarkable achievement.

Australia’s native history bears an abundance of culture, art and identity. Indigenous Australians created jewellery from the the environment, such as shells, seed, feather, bone and strung with hair or fibre. In 1770, James Cook navigated the east coast, naming it New South Wales under Great Britain. In 1783, the ‘First Fleet’ was sent under the command of Arthur Phillip, to establish a penal colony after the loss of the American colonies. Sydney Cove, Port Jackson was founded on the 26th of January, 1788. Australia’s connection to European fashion and sentimental ritual begins at this point. Convicts that arrived had only the most basic means of survival and attachment to their homeland. They had disparate skills, which were used to replicate the lifestyle and identity of their heritage.

In 1786, the Commissioners of His Majesty’s Navy advertised vessels to carry 700 to 800 male and female felons to Botany Bay, New South Wales for colonisation. The clothes they travelled in were their own, as there was no allowance for clothing from the British Government. On arrival, the standard issue was:

Jackets / 2 each

Waistcoats / 1 each

Pars breeches / 1 each

Shirts / 2 each

Hats / 1 each

Woolen caps / 1 each

P’rs of shoes / 2 each

P’rs of stockings / 2 each

Female clothes were just as basic, with no allowance for the landscape of their destination:

Jackets / 1 each

Petticoats / 2 each

Shifts / 2 each

P’rs of stockings / 2 each

Shoes / 2 each

Caps / 2 each

Neck h’dk’chiefs / 1 each

Hats / 1 each

Clothing in the subsequent years was not equipped to deal with the Australian environment, as the cooler climate was not considered. Clothing was made from osnaburgh, a cloth woven from flax, used to make trousers and frocks. It did not supply the protection needed for the variable elements of the region. As there were no stores, legal and illegal auctions and trading were common, treating clothing as a form of currency. 1790s New South Wales was a difficult and harsh place to live. Many were at the mercy of trade and poor governance, but the general assumption was that the colony was a place for convicts, with ladies fashion being seen as hopelessly behind those of England. This made it profitable for commercial shipping to sell clothes at marked-up cost to colonial women.

In 1803, Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) was settled as a British penal colony and part of the colony of New South Wales. Communications are the way that a set style can be interpreted through a growing community and the colonies relied on publications such as La Belle Assemblée, the Australian (1824), the Hobart Town Gazette (1816), the Morning Herald (1831) or the Sydney Gazette (founded in 1803). By the 1810s, there was a desire for weavers, dyers, dressmakers, hatters, milliners, shoemakers ands spinners. By 1804, a government ‘factory for disorderly females’ manufactured wooden cloth and by the later years, local wool production would lead to high quality and exportable merino wool.

Jewellery during this period came from the skills of convict jewellers sent to the colonies. Much of their skills were used for repair work (watches, spectacles), as well as moulding of teeth, weddings rings and miniature mounts. Commonly, these jewellers were transported for the crimes of forgery or receiving stolen goods. In the publications mentioned earlier, jewellers would advertise their skills, and through this, competitive production in Australia had begun. Much of the jewellery was imported or purchased at an auction room, rather than have the materials and resources to construct jewels this early in the colony. An 1828 census of New South Wales shows a population of 11,000, with 32 jewellers as members of trades.

‘Lane, Watchmaker, has received by a late

Arrival an Assortment of the following Arti-

cles, which. will be Sold on reasonable Terms, with

an allowance to Watchmakers, Wholesale Deealers,

and for Exportation ;–viz.

Clocks and Time-keepers, gold, silver, and metal

watches, best polished steel and gilt chains from

2s to 12s, keys and trinkets.-Jewellery, compri-

sing a variety of gold watch chains, seals, and keys,

au elegant assortment of plain gold, pearl, topaz,

chrystal, spangled, mourning, and fancy neck

chains, gold, topaz, coral, and enamelled crosses’

– The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Sunday 26th November, 1809

In 1813, Governor Macquarie enlisted the convicted forger William Henshall to cut the centres out of £10,000 in Spanish dollars sent by the British government to produce coinage and re-stamp them. Macquarie put penalties down in order for people not to melt down the coins for their silver value with the following:

And it is hereby further ordered and declared by the

Authority aforesaid, that if any Person or Persons shall,

by any Art, Ways, or Means whatsoever, melt down, im-

pair, diminish, scale, or lighten any of the Silver Money

hereby allowed to be current in this Territory, such Of-

fenders, their Counsellors, Procurers, Aiders, and Abet-

tors, being lawfully convicted thereof, shall be sent to

Newcastle aforesaid, and there kept to hard Labour for

the Space of Seven Years.

– The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Saturday 10 July 1813

The ‘holey dollars’ remained being melted, with some selling the silver back to England. Such was the need for survival in the colonies, as the opportunity to survive and grow was against the harsh reality of what could be gained through limited resources. Jeweller, watchmaker and metalsmith, Alexander Dick, arrived in 1824 and established his business in 1826. His wife was born in the colonies, Charlotte Hutchinson, and they shared interest in the business. On December 25th, 1826, Dick was convicted of receiving twelve dessertspoons, stolen from Colonial Secretary Alexander Macleay and e was sentenced to seven years at Norfolk Island. Hutchinson continued the business and continued it successfully after his death in 1843.

Gold Rushes

Victoria had its first settlement in 1803 at Sullivan Bay, but in 1836 was another division of New South Wales under the Port Phillip District. It separated in 1851 and was renamed Victoria, in honour of Queen Victoria, under the hope of being a ’Land of Promise’. This rang true in 1851, as gold was discovered outside Ballarat (Buninyong) and near Bendigo, creating a groundswell of interest in Victoria, with a population increase of 77,345 to 540,000 in a 10 year period. By 1881, this number had grown to 861,566. During this time, it produced one third of the world’s gold. People from India, California, China and Britain entered the goldfields, all looking for fortune and influencing production of jewellery to new heights. Where there is discovery, there is opportunity.

Gold was also discovered on the 12th of February, 1851 at Summer Hill Creek near Bathurst in New South Wales and in 1852, an alluvial goldfield was found at Fingal in Tasmania.

With the abundance and ease of access to the gold being mined, the production of Australian jewels grew an indapendent level of production and design. Goldfield jewels tend to be heavier in weight and highly embellished in their designs, featuring unique Australian-centric motifs.

These motifs are totems to the symbols that made the jewel possible. Symbols such as the mining pan, pick, shovel, sluice box, revolver or the nugget of gold itself, are very typical elements to find in these jewels. Miners rings are tokens of success, but the most typical style is the large brooch, with symbols typically flanked by a golden grape-leaf border, signifying prosperity. Diggers and travellers would purchase these brooches as souvenirs of their time at the goldfields, most commonly as a token from a differ to his sweetheart. Immigrant jewellers set up jewellery stores in towns near the goldfields, often due to their failure as miners, but the finer, larger and more embellished jewels were purchased from city-based jewellers.

This brooch from 1855 shows the perfect scenario of the miner at work. In jewellery, it only took innovation and industry to deliver a higher output of jewels. This can be seen in the Hallmarking Act of 1854 that allowed the use of lower grade alloys in jewellery. Pinchbeck and other alloys are common in jewels which identified with the look of what mourning was trying to achieve. Cheaper jewellery that looked large, with the elaborate black enamel, could be worn in costumes that were becoming larger and more voluminous. Australian jewels with the access to gold, which was often discovered on the goldfields and given to the jeweller to create, kept the large, popular styles of the 1850s and 1860s and utilised the gold to present these large scenarios. One must focus on the jewellers who created these jewels to see the level of skill that came to Australia.

“In May 1851, a few months after Edward Hammond Hargraves had published his discovery of gold, Bathurst shopkeeper Edward Austin arrived in Sydney with a nugget weighing about 225 grams. According to The Sydney Morning Herald (15 May 1851) it created ‘a great sensation’. Austin’s find fanned the excitement that was to shake the colony and create a rush to the Bathurst region. Choosing to remain in Bathurst, Austin made his fortune by providing diggers with credit to buy mining tools and then afterwards purchasing their gold. He commemorated his success with this brooch, which he gave to his wife, Mary Ann. For Austin, the brooch underscored a life of ups and downs. Born Elias Arnstein, a Bavarian Jew, he was apprenticed as a tailor when he went to England in 1831. After only two days in London, he was arrested and sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing a ring and two brooches.

The Austin brooch belongs to a group of ‘goldfields’ brooches of a type made exclusively in Australia from local gold between the mid 1850s and the mid 1860s. Massive and ostentatious, most were melted down when smaller brooches began to be favoured in the following decades or when they were sold for much-needed cash during the depression of the 1890s. Only a few have survived and most are not marked. Their provenance has been long forgotten. “ – Powerhouse Museum

Naturalism and its usage post 1860 was a reaction to the Gothic Revival period, where many of the values of the middle ages were bought back to become the dominant style since the 1820s. The wealth that was invested in jewellers came from the new wealth that now could be attained by classes other than the aristocracy. Money from oil in the United States, gold that was dug from the ground and wealth through trade and production allowed for more practice of design that was practiced by approved artisans to the crown. As the gold from the goldfields was so closely related to the jeweller who was designing it, more unique designs could exist. Australia offered flora and fauna which is unique to the rest of the world. When these symbols are interpreted in jewellery, their image is arresting and clearly identifiable as being uniquely Australian. But the artists who designed these jewels were predominantly not born in the colonies, they were emigrants. This level of talent and detail is captured with the eye of the European, in this case, Joachim Mattias Wendt.

“Established by Jochim Mattias Wendt (1830-1917) in 1854, J. M. Wendt was a prominent firm of Adelaide silversmiths, jewellers and retailers throughout the late nineteenth century. Born in Schleswig-Holstein, J.M. Wendt came to Adelaide in 1854 and established an enduring and productive business first at Pirie Street and then in Rundle Street. (The duchies of Schleswig and Holstein were much fought over by Denmark and Prussia particularly until in 1866 they became one as part of Prussia through the Peace of Prague.) He collaborated with Julius Schomburgk, who later worked in his own right. It is believed that between 1863 and 1870, much of the work produced under the Wendt name was Schomburgk’s. (J.B. Hawkins, 19th Century Australian Silver (Woodbridge: Antique Collector’s Club, 1990), vol. 2, p.61). Wendts sold imported jewellery and silverware and produced its own jewellery. The latter, in gold, were entered in the Sydney International Exhibition 1879 and Wendt was ‘awarded a First Degree of Merit for Jewellery and Silverware’.

Unlike some of its competitors, Wendts managed to weather the financial crises of the 1890s. An advertisement from 1895, shows that they advertised themselves as ‘The Cheapest House in Australia’. Wendts produced a wide range of objects in silver and jewellery, some of the best known being the candelabra, inkstands and silver mounted emu egg pieces which used Australian flora and fauna and figures of Australian Aborigines. Many were commissions. The Powerhouse holds a significant collection of pieces by Wendts. (2002/78/6; A7283; 91/142; 85/412 and 2002/81/2) A number of other pieces by Wendt and or Schomburgk were lent to the Powerhouse Museum for the exhibition ‘Australian gold and silver, 1851-1900’ held between March 1995 and March 1996 at the Mint Museum, Sydney.” – Powerhouse Museum

Even the more functional, daily accessories maintained a higher quality. In the case of this watch chain, the level of detail to the bar and linkages are exceptional in their intricacy. Life as a jeweller was not easy in the goldfields, nor was it for any of the diggers. In this chain, the craft of Sylla Denis is on display and Sylla tried his hand at mining, but moved back to his craft:

“The firm of Denis Bros was founded by Sylla Denis who arrived in Melbourne from France in 1853. He first tried his luck – apparently unsuccessfully – on the Ballarat goldfields and then moved to Melbourne to set up a jewellery business about 1857. By 1861 he had been joined by his brother Victor and subsequently by Gustave Lechal, their nephew (until 1889). This substantial fob watch chain would have been made at the time when Denis Bros enjoyed the highest esteem from their customers having received a First Order of Merit for their gold and silver jewellery at Melbourne’s ‘International Exhibition of Arts, Manufacturers and Agricultural and Industrial Products of All Nations’, 1880-1881.” Powerhouse Museum / A. Schofield, K. Fahy, ‘Australian Jewellery, 19th and early 20th century’

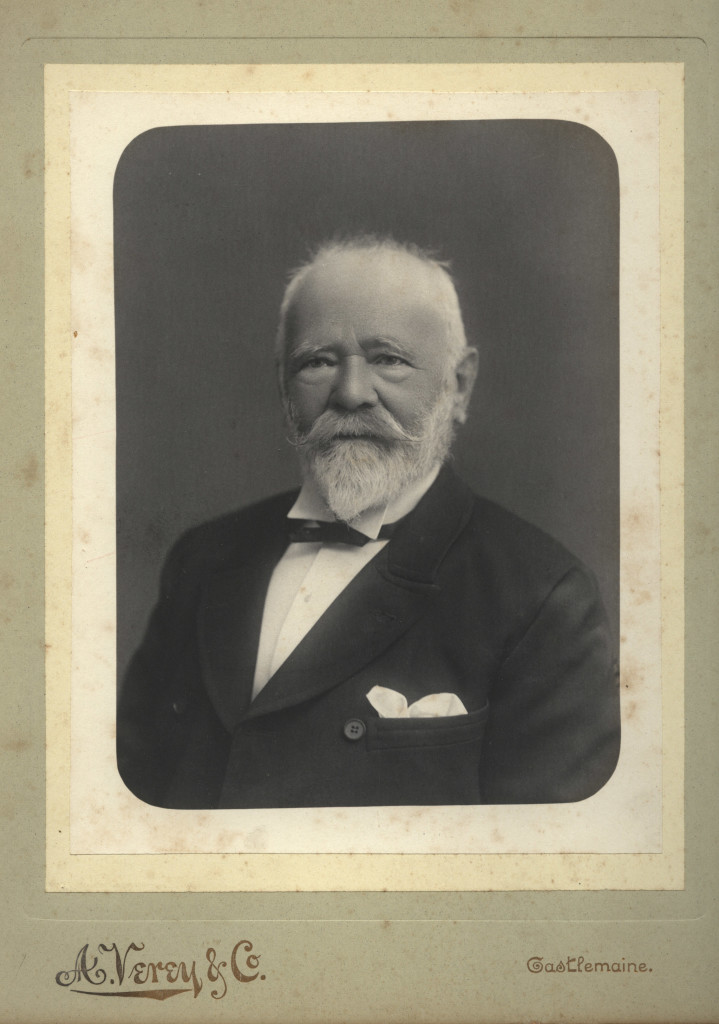

Ernest Leviny was another such silversmith and jewellery. Originating from Budapest, Hungary, he learned his craft in Paris and moved to London, where he began a business with a Russian jeweller. He arrived at the Castlemaine goldfields in 1853, but his equipment was not compatible for the alluvial gold mining and his his labourers left him. In 1854, he established a jewellery and watchmaking business in Market Square, Castlemaine and invested in mining and property. While predominantly utilising his skills for metal smithing silver, as this was the more popular request, his designs still remain in Castlemaine today.

Australian jewellery was featured in the International Exhibitions from the time of the gold rush. Notably, the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855 featured the two finger rings set with three native ‘diamonds’ (‘Killiecrankie’ – white and yellow topaz from Flinders Island in Bass Strait), polished Tasmanian gemstones and a large brooch with Tasmanian beryl aquamarines and another with topaz.

The exhibitions held in Sydney (1879) and Melbourne (1880) allowed for Australia to be seen on the world stage, presenting the jewels of the labour that had developed from global emigration. The confluence of such skill and access to materials had put Australia on a global level and the quality of metalwork that was produced was of its own class.

From the opportunity seen in the abundance of what Australia could provide for and the difficulties that it actually contained, the culture of Australia was still dominated by the British and that is where the primary cultural influencers came from. In the case of jewellery styles or the periods of mourning, honouring the customs established in court were standardised. Jewellery is the presentation of identity in a culture, so the jewels worn related quite closely to those back in Europe, however the Australian embellishments of sentimental jewellery led to a better display of independent design. Brooches that have the embellished flora and fauna designs in the gold surrounding locks of hair or photographs are a good way of seeing how a popular universal style still can be interpreted through Australian identity. The artists who created these jewels are not of one singular heritage, but came together at a time to understand a foreign land and reinterpret it through the lens of metalwork.

Decline of Mourning and Leading Change

The customs of the 19th century were challenged throughout its latter half. As has been discussed in other articles, new wealth and a generation of mourning created a youth which did not want to be imposed in a static culture. There was much greater access to design and art from new sources and the circulation of this art could easily be global through transit. The following article featured in The Australasian on Saturday, 6 October, 1900 shows just how Australia’s reaction to legacy and embracing of change through mourning alters fashion for a society:

MOURNING.

By QUEEN BEE.

Reform, or rather rebellion against theold order of wearing mourning, is increasing day by day. The great mass of women now absolutely decline to invest themselves with quantities of crape and other fabrics that make outside shows of grief. Small wonder there is this change. The old order of things has always been desperately inconvenient, unbecoming, and costly. In no instance has this been so marked as in the case of the Widow. Even in the house she had to wear a cap that nearly hid all her hair, and finished with long “cumbersome streamers to below the waist. Then it became eligibly diminished in size, if not in significance, and when it took the Marie

Stuart form had an only recommendation – its becomingness. Bonnets, too, were heavily draped mounds of crape, finished with a full cap and wide white strings.Fortunately it is in the widow’s mourning that the greatest and most noteworthy reform has set in. The higher the position of the widow, the greater the change, for it is in this station of life that good taste and commonsense generally prevail.

The first thing to disappear has been the widow’s bonnet, replaced by hat or toque. With regard to the dress the now old-fashioned bombazine is replaced by any light black texture, not even excepting glossy materials, such as grenadine, voile, crepe-de-chine, &c. Chiffon and silk muslin take the place of crape, but as crape is now so lightly and becomingly made up without the additions of heavy textures, save a light silk lining, it is not altogether excluded. That black should be worn is light and fitting, especially in the early months following bereavement, and as it is now made it is above all things merciful.

Left in the hands of someone who will deal with the matter carefully, there is really nothing more refined than black. But it is quite a different matter when there is a hurried search, and anything, so long as it is black laden with crape, is the result. In a short time the wearer begins to wish that the money had been spent more

wisely, and that a-lighter gown and toque or hat had been chosen in place of the heavily-laden bonnet.In the case of very old ladies some of the old order of things remains. They cling to old traditions; besides, a bonnet is generally more suitable to them, as, perhaps, even before their mourning it was their every-day style of headgear. But it does not follow that it should be of crape. Fine, dull mousseline is more correct, and answers

its purpose just as well. In addition, its lasting and cleanly properties make it more desirable than crape. As to trimming, there are endless varieties of dull embroidered lisses that mingle well with the mousseline if wished, but reallv pretty bonnets are made solely of the former. This latitude is permissible with regard to the dress. It may be of any soft black material, with or without the addition of crape. The latter is added with such an amount of taste that all its old heavy appearance belongs to the past. Strappings of it are daintily stitched on the bodice and the skirt, no matter whether it be in the simulated under-skirt style, or in long, plain, flowing lines, the variety this form of ornamentation may take being endless.In the many other instances of wearing mourning the latitude is now even greater, so much so that it is hardly apparent to the outside onlooker. Smart in construction to a degree, and of the lightest textures, there is nothing uncomfortable about it, even on the hottest day. Fine tucking,and hice or guipure insertions form the collar, bib, yoke, or chemisette. Where something a little warmer is required stitched silk takes the place of the lace or guipure. Such mourning is only worn for the first few weeks or months, according to the relationship in which commonsense asserts itself.

The styles of to-day seem to be particularly well adapted to the periods of half mourning: indeed, they might have been designed for the purpose. In black and white this is particularly so. Never was it more fashionable, even with those who are not called on to wear it for necessity. The most charming of light textures have been brought into vogue for mingling with lace, and when shown up by the silk lining are elegant to a degree. Mauve is now quite as popular as grey always has been for half-mourning wear. So is all white with only a suggestion of black here and there, narrow ribbon velvet or black silk bands supplying this suggestion of black, with small jet and steel Duttons. These ornamentations also hold good for mingling with grey and mauve, to which they add much smartness, especially if a black hat be worn with either colour.

Those who remember the time when every article of jewellery had to be laid aside for the period of mourning, and give place to ornaments of sombre dull bog-oak or black enamel set with pearl, will rejoice in the introduction of these more rational customs. Of course, the fewer coloured jewels worn the better taste; diamonds and pearls are, however, exceptions, whether set in gold or silver. They can at all periods of mourning be freely worn, as there is nothing objectionable in their appearance; on the contrary, they do much to enhance the sombre effect of the back.

In these days, when people who are in mourning leave their seclusion so soon, evening dress enters into the mourning outfit pretty quickly. Black chiffon, crepe de chine, mousseline de soie, and the like

make the smartest dresses, and those that are in strict accordance with mourning requirements, and with the soft clinging styles of the present fashions. Such dresses are unrelieved by any ornamentation, save dull sequins, or embroidery, or a touch of white tulle or chiffon on the bodice.Distinct marks are the times are the short periods of wearing mourning, and the brief retirements from social gatherings. It is said that we no longer mourn our dead so far as outside appearances go. The sincerity of sorrow and remembrance make amends for the outside show of nursing grief for the mere semblance of doing it, if we are now erring on the other side it is ‘din the common-sense one, which has much to commend it. It is still understood that those who shroud themselves in crape must remain in seclusion until all that is put aside. This arbitrary law has much to do with late reforms. Society rebelled against it by declining to wear crape any longer and lightened the details of dress and thus lessened the obligations to seclude themselves from social functions for an unreasonable time.

With the extension of of all these new ideas complimentary mourning has no longer any significance. It be worn for connections, but for mere friends, and then only for a week or so at the outside.

Society was ahead; the colonies were not behind as they had been, but were advanced and leading challenging thought. This article clearly articulates the flavour of the time, being highly incredulous towards the old way of mourning and fashion. As is usual with mourning, the fashion may have been popular, but the sentiment is eternal. As long as there is a loved one who has passed on, the feeling of love and loss needs something to retain a memory. The Australian boxer, Les Darcy (1895-1917) was successful and controversial for his time, stowing away during the First World War to fight in the United States. He died young from infection and this locked was created in his memory:

A sentimental token worn by his sweetheart shows all the signs of sentimentality during life and all the elements of mourning after death. The hair, the photograph and the setting are all typical of the previous centuries and retain the same sentiment. Love is the basic catalyst for memory, be it emigration to a new land to create for a family or the giving of a gift to remember someone by – love generates these things.

Thinking that colonial Australia could not adapt, or lead, style is not correct. It offered abundance for those seeking establishment and opportunity. At the right moments at the right time, catalysts appeared to offer this to the world and those who endured, created. There’s not one element that makes something ‘Australian’ beyond the basic interpretation of the landscape in a jewel. Different cultures applied their own beliefs and established their own communities within the colonies and many still flourish today. Under the British flag, mourning and sentimentality was standardised by the giving of gifts or wearing of tokens, but the identity was morphed by the landscape of Australia as seen through foreign eyes.