Butterfly Symbols and 19th Century Jewellery

As with all symbols, there aren’t simple explanations for them when they transcend one culture or time. Organic symbols have lasted as long as cultures have written history, making them adapt. With the various classical revivals, symbols have become resurrected in Western culture time and time again to take on a homogenous understanding of what their symbol means.

The 19th century had a great deal to do with our standardisation of ritual and identity. Political change and tension in the 1840s had cemented things such as our Christmas rituals, the white wedding, the Christian family and the symbols of love and grief. A mortality rate of twenty-nine (23 per 1,000) put the focus of the Industrial Revolution and higher density populations in the light of what it was to be within a family which could grow in a rapidly moving society. There was more freedom for wealth to be gained and that to grow a family, yet there was more danger in terms of what it took to achieve this status.

The Enlightenment had much to do with empowering individuals and the family unit to grow under the light of personal wealth and value. Growing from the Neoclassical period, a new focus upon the ‘self’ in society had changed what it was to be in love or grief for another person in fashion. Historical discovery in Herculaneum and Pompeii in 1711 led to even further cultural connection to the classical world, with further excavations resuming in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians and spurring forward a new perspective of the individual and identity within the Western religious paradigm. From the Neoclassical period of art and fashion, jewels evolved to depict the individual and move away from the literal identity of death and decay, seen in the memento mori jewellery with skulls and symbols of final judgement by god. This occurred during c.1760, where there is a fundamental shift in costume and jewellery, which was worn for the identity, to be connected to history rather than just for utilitarian purposes across society. The 19th century tried to pull this back to its traditional roots, but this created a schism between personal and fundamental thought in the Gothic Revival period.

As such, the butterfly is a symbol that works throughout cultures and was represented at the time of this brooch (1839) as a direct result of the Neoclassical period and its installation of symbols that could be adhered to from the perspective of cultural identity. The butterfly represents the soul in a classical and an organic way. From the organic perspective, its meaning is derived from the three stages of the life of the butterfly; the caterpillar, the chrysalis, and the butterfly. Naturally, this is the development of the soul through the age of human growth and death, flying off to the heavens.

As with all symbols that represented in art from the middle ages onwards, connotations towards Christ were necessary. Christ’s three stages are symbols of life, death and resurrection, once again related to the butterfly’s three periods of life. this gives artistic licence to use the symbol in classically represented art and not be scrutinised for its personal/humanist sentimentality.

From its classical point of view, its relation to Psyche cannot be overlooked. The daughter of a king and queen, Psyche was considered to be as beautiful as Aphrodite. She became Eros’ (Cupid) lover when his mother, Aphrodite, asked him to make her fall in love with the ugliest man on earth. An accident caused Eros to prick himself with his golden arrows and he fell in love with Psyche. They were married and had a child, Hedone (lust) and Aphrodite would allow the marriage if Psyche passed a test.

Psyche was tricked by her sisters, resulting in a lack of trust between them, forcing Eros leave. Aphrodite put Psyche to four tasks, which resulted in her immortality and acceptance as a wife for Eros and not a competitor towards Aphrodite’s beauty. Due to this, she was symbolised as the Soul seeking union with Eros (desire) and is depicted with butterfly wings.

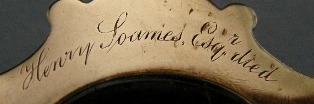

But how could a onyx cameo butterfly in a very classically designed brooch exist with such prominence in the 1839 era? Victoria gained succession in 1837, two years before this brooch was created and she was married to Albert in 1840, leaving this brooch in a time that didn’t have the influence of a monarch that was defining a particular style of design. Classical influences, combining with the Gothic Revival style and the Rococo elements that it resurrected are seen in this brooch. Even from its simple design, the nature of being large and bold worked well with the growing size of necklines, puffed sleeves, wide shoulders and pleated skirts held out with starched petticoats.

This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth.

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period.

Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

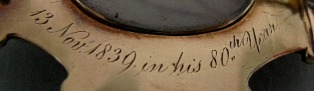

Butterflies were not just a fancy in design of the 1840s, they were a popular motif. As can be seen in this very sentimental brooch, the hair of an entire family is woven throughout the jewel, from the 1839-1842 period showing the deaths of two people. It is the perfect representation of the soul and its development and departure, utilising hair in a way that makes it more precious than any gem which could adorn it. This is the representation of a family and quite unique.

Left wing: ‘C.P.V.’ and ‘L.A.V.’ (top)’; ‘A.M.D.’ (below)

Body: ‘L.M.’ (top), ‘D.R.C.’ (middle), ‘C.C.E.C.’ (below)

Right wing: ‘H.S.C. obt 1842’ and T.C.C. obt 1839 (top); ‘CC-LC’ (below)

Organic themes in jewellery became popular in the first quarter of the 19th century, much due to the materials that were available to the goldsmith. In 1804, the Napoleon’s Empire was announced and luxury trades were renewed with vigour. Bijoutiers, who worked in ordinary materials and joailliers, who worked in precious stones benefitted from this rise in luxury, with Napoleon requesting the jewels from the former kings of France to be set in the Neoclassical style, essentially connecting him to the Greco-Roman empires. His coronation crown was decorated with cameos and his passions for the antique world led him to establish a school of gem engraving in 1805. If ever there was a height for the Neoclassical period, it was this connection to it. How other societies would reflect this moment is seen in their contention or support of Napoleon. Here is a person who is appropriating the classical world in a time where it had been in mainstream thought and fashion for around forty years. International tension would only lead to the decline of this style, as cultures needed to obtain their own identities in jewellery fashion. A great push to the Gothic Revival style in England has its roots in this.

Simple designs and smaller jewels following in this early 19th century period. The geometric shapes, ovals, circles and rectangles became popular, with the Greek key pattern utilised often in jewels. It was about balance, with many patterns being taken directly from Greco-Roman architecture and detail. During this time, until his remarriage, Josephine was the bastion of style, maintaining the fashion which people would covet.

Through the necessity to utilise finer designs with lesser gold, the jewels of the early 19th century required a change in the large, dominant gold housings of the Neoclassical era, such as the navette style of ring or brooch. Making delicate and pretty jewels with elegant design allowed for an organic focus in jewellery to accommodate decorations of fashion that could be worn with pride and identity in high society.

Contemporary jewels for the purpose of fashion don’t relegate the motif to simply mourning. With the above chased two-colour gold brooch in the form of a butterfly set with rubies, emeralds and pearls with an empty compartment in the reverse, the element of sentimentality is there for the compartment to be filled with hair, however the use of materials doesn’t denote a mourning purpose. It’s simply a love token given for the sake of loving memory and desire. It is a perfect representation of the 1830s and how the language of jewels and gems had changed from their very literal Neoclassical depictions of love and death.

In this chased and engraved gold brooch set with cabochon-cut moonstones and a turquoise in the form of a butterfly, the organic flavour of jewels is represented perfectly. Capturing a style that would be popular in the Art Nouveau movement a century later, the butterfly is worn with the same fashionable style upon the bodice or neck.

However, the organic style of jewellery never left the popular lexicon. Butterflies lasted through the 19th century and to today, being a design which is beautiful, easy to adapt in terms of materials and colour, as well as highly decorative.

Once more, a similar style maintains during the 1850s, in a silver brooch set with jasper, agate and bloodstone in the form of a butterfly. Its style may be less detailed than it had been in the precious decade, but it still shows the same basic style and construction. Butterflies allow for a high degree of colour and material in their jewellery representation, so they always retain a popular identity. Going from the earlier examples of mourning and sentimentality, the butterfly transcends this as an identity and lends itself into the fashion of beauty. Be they a keepsake to a loved one, there is no sentiment, but they could be purchased for their simple aesthetic affectation. The mid 19th century saw the installation of many of the affectations in lifestyle which we appreciate today. From the ceremony surrounding events such as Christmas, to the very symbols seen in modern cemeteries, the elements of our daily lives are still under the same values that the 19th century imbued within us. To understand just how radical this was, it is important to look at the changing style and values for this very time.

Innovation led by Albert, Prince Consort cannot be understated for its values and impact upon society. The Great Exhibition of 1851 came about during a time of European and Latin American economic turmoil in 1848, leading to revolutions following the rise of nationalism. Albert’s dedication towards acknowledging the underprivileged and offering financial and educational assistance was an incredibly bold stance for the time, particularly when his family in Europe was being threatened. Since 1843, Albert was President of the Society of Arts, which, from its annual exhibition, became the basis for the Great Exhibition. Based in Hyde Park within The Crystal Palace, the value of science, art and industry became a matter of pride for British society, which is a progressive step and one that shows the great innovation of Albert, himself. As a counter to revolution, The Great Exhibition stood fast and as a catalyst for art and innovation, the impact upon jewellery design that was revealed through new techniques of metallurgy and style resonated back through society.

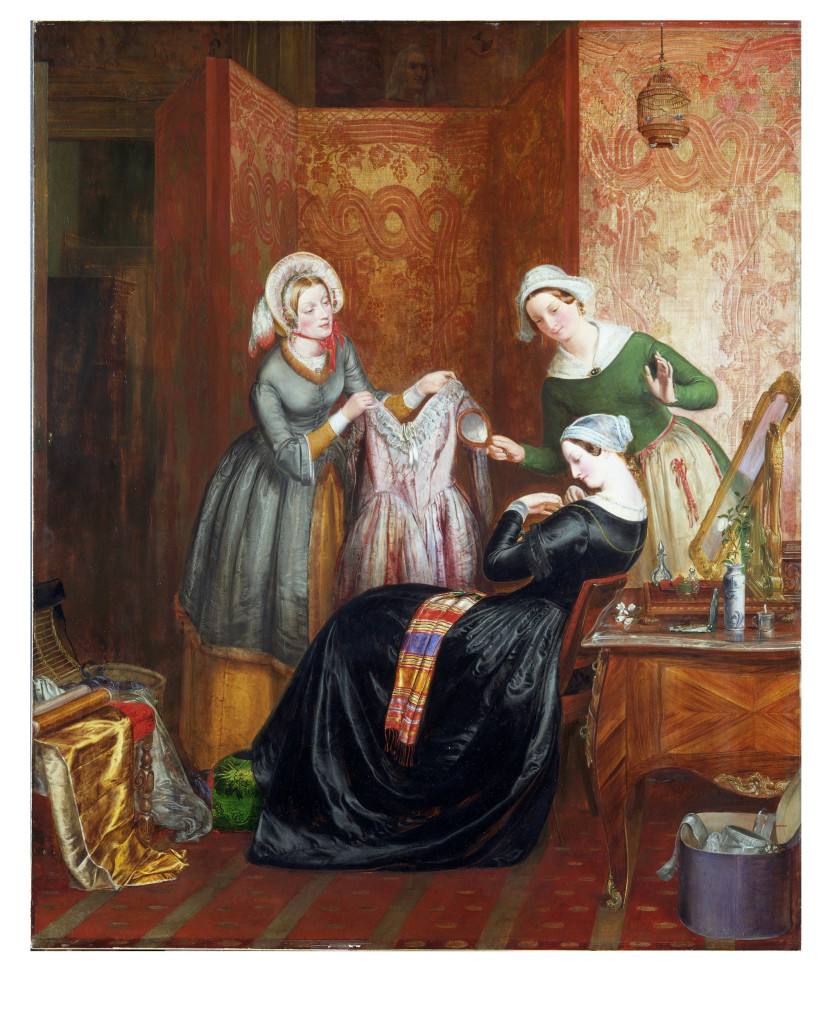

The 1850s led much of this standardisation, with the family elements that were instilled by Victoria and Albert becoming popular in terms of literature and fashion. New challenges, such as Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, threatened the Christian family that had been established by Victoria and Albert, but fashion was still permeable. Romanticism flourished in literature and art, notably by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late 1840s. Looking towards medieval culture for inspiration and harshly turning against realism, many of the mourning and sentimental symbols that are common today in jewellery and funerary art were carried through by their use in art. Within literature, one must not look past Charles Dickens for the usage of Victorian sensibilities and values within his writing.

Albert died in 1861, effectively locking Victoria in a period of perpetual mourning. The effect of this was felt within jewellery design, leading to a very static period for jewellery design in the remaining century.

Bolder style was in its element during the 1860s. This can be attributed to the mourning of Queen Victoria from 1861, but also tells of the evolution in costume and everyday dress.

Fashion had changed during the 1850s and 1860s, installing larger styles of the mid-Victorian era to become popular, with female fashion becoming larger and the jewels needed to adapt.

Represented in the 1870s, thirty years after the brooch in this article, this French brooch shows how the butterfly could be represented in popular jewellery for its time. A chased gold brooch in the form of a butterfly with folded wings has a French warranty mark and illegible maker’s mark, but clearly represents that the motif was not lost of taken over by another popular movement. Symbols adapt over time, but they don’t simply disappear.

Of course, as symbols develop and have periphery meanings, they still retain the identity of what had come before. The butterfly still retained its spirit connotation a century after it was reintroduced into society through the Neoclassical era and these earrings show just how the mass production of jewellery was globally profitable through their need:

“These butterfly earrings are typical of the cut steel goods exported from France to much of Europe and America in the second half of the nineteenth century. The flourishing trade was bolstered by the need for jewellery to wear during periods of secondary mourning (an interim period between full and semi-mourning in the Victorian era) as well as by fashionable status. In London in 1882 it was reported that steel butterflies had begun to perch on bonnets.” – V&A Museum

Mourning costume had, by the latter century, connected costume and function for women. Dresses of separate bodice and skirt were worn in bombazine covered in crape. Underwear was often white chemises, drawers and under petticoats slotted with black ribbon. Black caps, crape trimmed bonnets, and long veils. In these steel cut butterflies, the element of fashion and mourning were intrinsically linked.

First mourning lasted one year and a day, outdoor garments for this would be shown by the plainness and amount of crape, jet jewellery was permitted. After one year and a day, Second stage was introduced. This involved less crape and its application to bonnets and dresses became more elaborate. It was frowned upon if this period was entered into too quickly and it lasted nine months in all. The Third stage (or Ordinary stage), introduced after twenty-one months, involves the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted.

Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months. The English Woman’s Domestic Magazine stated that ‘many widows never put on their colours again’ and this was quite a statement for the identity of the woman, which was held under the veil of mourning and family symbolism for the rest of her life. Hats, shawls, mantles, gloves, shoes, fans all changed during mid century, and pagoda sleeves from 1850-70 were fashionable, designed to be stitched to the outer sleeve to cover modesty from the lower arm and wrist. Wide skirts from the 1850s-70s, tie back fashions of the late 1870s and the ‘S-bend’ look of the early 1900s all were adapted to mourning fashion, without a clear definition of difference between them. Throughout the post 1880s decline, in the 1890s, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure.

Platinum, first found in South America, though strong and resistant to tarnish was seldom used in jewellery because of its rarity and the high temperature required to melt it. Its modern role for setting diamonds dates back to about 1870 although it did not become widespread until around 1900.

Diamonds were no longer reserved for grand occasions. By about 1900 it was even fashionable to wear them in the morning, a change in taste encouraged by the flow of stones from South Africa which began in the late 1860s.

The decline of the mourning and sentimental industries was not exclusively ‘mourning’ related, but an actual change in fashion and social taste. How to present sentimentality and love in a public forum through a jewel was very different in the post 1901 environment than it had been since 1861. Two generations had passed under a very static monarchy, which originally had been the cultural impetus for fashion and art. Society would look to the monarchy for various elements to adapt, the most noteworthy being George IV, but Queen Victoria had established the ‘ideal’ family unit under a Christian value system and then fallen into perpetual mourning. Despite the underpinning realities which may contradict this, it was then, and still remains, a value system that Western cultures still use today. Everything from the establishment of wedding ritual to Christmas rituals and their surrounding affectations are built from the 1840s, yet there was a rebellion in society that needed to create its own style and movement to break apart from what was considered a rigid perception of mainstream fashion. This change came about in the 1890s.

Throughout the post 1880s decline, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure. While this perception is very affecting to mourning, the sentimental industry and its production of jewels as tokens of love were changing rapidly. There were art movements, such as the Arts and Crafts movement, which built upon the ‘natural’ elements of beauty and design to be interpreted in architecture and industrial design. This was a counter-reaction to the industry that had dominated 19th century life, by moving back to organic styles. This is much the same as the Rococo movement in the early 18th century, which reacted against the dominant Baroque styles with organic flourishes. This, in conjunction with the Enlightenment, led to new perceptions of the self in the Neoclassical movement and in the late 19th century, we see the same revolution in cultural style.

Through the evolution of 19th century butterflies in jewellery, there’s a clear continuity of growth and social change. From costume and how things were worn in mourning regulation, these ornate and natural jewels would continue on through the Art Nouveau period and still remain in production through various accessories today.

A mix of classical culture and social change made this brooch fashionable and also quite poignant for its time, which resonates today in its beauty and sadness. The soul may be off to heaven, but the fact of this brooch remains.