British Demand for Mourning Jewels

Commercialising identity in the 19th century was as important to the British Empire as success in any war. Building a culture of commerce creates a cycle that venerates special occasions between family and friends, which in turn grows a healthy economy.

Growing an economy through fashion and identity feeds an Empire that is constantly becoming global. Materials brought back to Britain are coveted and used, influencing an elitist society to create an aspiration that was paraded in magazines and pamphlets. Men and women both fed the fashion industry, ranging from a growing middle class to the affluent aristocrats who lived on their family income and flaunted the latest fashion from at home and abroad.

Late 18th century lifestyle promoted this society, with fashions from France setting the levels of style that would be aspirational for a fashionable British lifestyle, with lesser deviance from presenting personal identity as aligning with Catholicism. Attitudes that utilised the mythology of medieval chivalry and promoted romance gave sentimental expectation in society a set of values of how courtship and behaviours around death rituals should be.

Visual identity in the 19th century was important to create stability in an increasingly global, industrial world. European colonisation of the planet was rapid and viable in a way that a far, remote, outpost of an Empire could be controlled through rapid seafaring transit and international cabling. By the time of the first transatlantic telegraph cable on August 16, 1858, the British Empire stretched from Europe through Asia and Africa to the Pacific, spanning the globe and exploiting the bounty of the lands that it had appropriated. 1/5th of the globe was populated with those within the British Empire, so a strict method of dressing and behaviour was essential for cultural stability.

From the 18th century, formal rules around sentimental behaviour were being controlled more by the aristocracy and the monarchy, with clear social parameters creating social values. This could be the act of giving a gift of a locket with a portrait inside to mark a betrothal or a jewel depicting a scenario of mourning to be acceptable for a family’s grief.

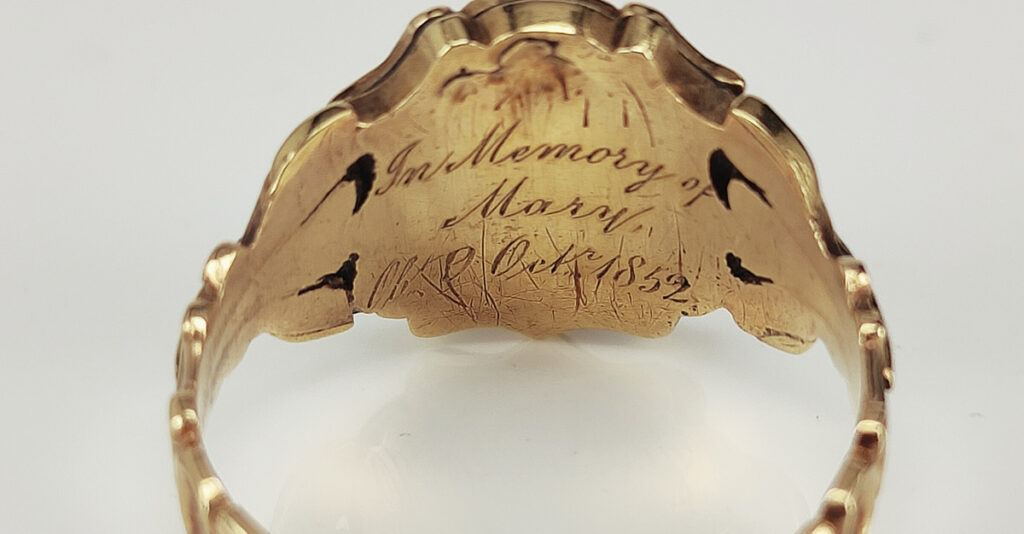

Mourning rings designed in this style were important reminders of how a family’s wealth could prosper during the 1850s. An upwardly mobile middle class benefited from business ownership, made possible from the urbanisation and profit generated through the Industrial Revolution. Retail was a concept that grew from households opening up to sell products in the 17th century, but now the 19th century became the template for capitalism and lifestyle. Jewellers, goldsmiths, textile manufactures, retails and hair artists all contributed to the mourning industry of product manufacturing and they thrived in this commercial environment. Demand for rings and the fashion of death benefitted society and businesses internationally.

Jewellers of the 19th century reacted to the demand for jewels such as this, which was growing from the late 18th century. These jewellers thrived on this business, but it did not always guarantee the success of their business.

The Jeweller

Gold and silversmiths of the 18th and 19th centuries increased in number with urbanisation, industry and population growth. As there was a high demand for mourning jewellery in the late 18th and 19th centuries, jewellers needed to cater to this growing market. If profit could be made from death, a jeweller could substantiate a business and maintain a family.

Hallmarks in jewellery identify the maker of the jewel, but not the seller of the jewel. Tracing a mourning ring to its inception is a relatively simple process of identifying its hallmarks, which should have the sponsor/maker mark followed by the metal/purity mark, the Assay Office mark to show where the jewel was tested and marked, then the date mark. These small stamps, which are generally found inside the band of a ring or at the reverse/inside of a locket, were required to maintain the quality of silver and gold articles to a Crown standard. For the purposes of mourning jewellery identification, they tell an even more important tale than the name and date of death of the deceased.

Matthew Govett was a late 18th century maker, who began studying under James Richards, a goldsmith and watch case maker of Bridgewater Square, in 1781. Govett established himself in Ironmonger Row and took an apprentice, Joseph Potter, in 1818. Govett passed away in 1823, leaving behind many examples of his mourning jewellery, particularly from the turn of the 19th century.

James Chafey Esquire passed on at the age of 71 in 1802, leaving behind a mourning ring of black and white enamel inlay with the stamp of Matthew Govett and a contemporary date of manufacture inside the band. In the styling of the ring, the simple shape of the even enamel lines makes it quite a fashionable style, contrasting with the also fashionable Neoclassical designs that were popular during this time. Stylistically, this ring does not conform to contemporary design, with the large ‘navette’, north to south, shape of the ring accommodating an allegorical scenario of death painted on ivory. Rings such as these were often painted in sepia tones, with a weeping willow flanking the top of the design, an urn or tomb in the centre and a Greco-Roman female figure weeping next to the urn/tomb. Chafey’s ring made by Govett is simple, stark and becomes the vision of a tombstone worn on the finger. Gold content in this ring tests at 22 carat, making this a ring designed for someone at the higher level of society.

Benjamin Denman passed away on the 31st of January 1803 at the age of 33, with another ring attributed to the hallmark London 1802. Govett’s hallmark is displayed on the ring, which has survived in better condition than the now lost enamel. Its design is identical to the Chafey ring, with the difference being the name and date of death. For these bands to have been made at volume in a new geometric design, Govett would have been required to embrace a quickly changing design aesthetic and clearly this allowed high turnover.

Popularity with a maker promotes business and increases demand; they have a promotable brand. Govett’s clientele reflects the adaptability of his product. Sir Stephen Lushington, 1st Baronet, Member of Parliament and three term chairman of the East Indian Company passed away on the 12th of January 1807 and it was also Govett who created his mourning ring. From 1782 Lushington was a director of the East India Company, deputy chairman from 1789-1790 and chairman for three terms: 1790-1791, 1795-1796 and 1799-1800. He was a Member of Parliament from 1783-1784, returning to parliament in 1790 where he remained for the rest of his life. He was created a Baronet on 26 April 1791. The Lushington Baronetcy of South Hill Park, Berkshire still exists today, with the 8th Baronet born in 1938. Sir Stephen Lushington died in 1807. His mourning ring reads ‘SIR STEPHEN LUSHINGTON – BART OB 12 JAN 1807 AE 63’.

Given the status of Lushington and the quality of the contemporary rings, it would be easy to make assumptions about Govett as a goldsmith. His quality is clear, his style is unique to its time and it could be considered that the way he approached being a goldsmith with a focus on mercantilism allowed him to find the right market for his product and expand upon it. Death is a certainty, so why not exploit a new style for the benefit of business?

Having his origins as an apprentice under Joseph Potter in 1781, Govett’s experience in teaching and mentoring other goldsmiths his own craft also opens an understanding of the challenges faced by the human behind the business.

On the 28th October 1812, Govett testified at the Old Bailey:

CHARLES WILLIAMS.

Theft: theft from a specified place.

28th October 1812

Reference Number t18121028-47

Verdict Not Guilty

Related Material

Associated Records

888. CHARLES WILLIAMS was indicted for burglariously breaking and entering the dwelling-house of Matthew Govett , about the hour of eleven at night, on the 6th of October , and stealing therein, two watches, value 2 l. twenty-four watch-cases, value 12 l. and eighty ounces of silver, value 20 l. his property .

MATTHEW GOVETT . I am a watch-case maker . I live in Ironmonger-row, St. Luke’s . The prisoner was my apprentice . He left me in Whit-Monday. He had not resided with me since I rent the whole house. I and my family sleep in it. The shop is attached to the house. We can go to it without going into the street.

Q. Is Hardcastle an apprentice of yours – A. Yes, and Miles. They sleep in the shop, in the same bed.

Q. On the night of the 6th of October, did you see any of your property that were put under the bed – A. I did; there were two ingots of silver, about eighty ounces, in a drawer, with watch-cases finished and unfinished, and two watches also.

Q. Were they entire watches – A. No, only parts of watches. There was a drawer with silver watch-cases, and a box of silver cuttings, and different descriptions of silver. This was all safe on the 6th of October. The value of all was nearly eighty pounds.

Q Did you see Hardcastle and Miles in bed that night – A I did. I looked through the window and saw them in bed. They went to bed before I did. They usually go to bed about half after ten, seldom later.

Q. I believe you never found any of your property again – A. No, except some little silver pendants in the morning. I went to bed a little after eleven, and my house was perfectly secured.

Q. Were you the last person in the shop – A. No. A lad of the name of Baldwin locked up the shop. I locked the street door myself. Before I went to bed the house was fast in all respects, as to the front of the street.

Q. How could any person get into the shop without getting in the front way – A. By the back way it opens into a place where there are new buildings.

Q. Could any person get into your shop without getting into some part of your premises – A. They must get into my yard. The yard is fenced from a public passage, by a wall. In the morning, a little after six o’clock, I was called up by Hardcastle. I went into the shop. I perceived the drawers were all gone excepting two. They had taken the contents, and the drawers. There was no appearance of violence to the shop. I found a window open in the shop. I went to the window to see if I could see any footsteps outside. I found none. There was missing four or five boxes, which were emptied. The drawers, with two ingots of silver, and the watch cases, were all taken away. Hardcastle then went out of the shop, over a wall, and brought back an empty box, belonging to the shop. That is all I have recovered except four pendants. In consequence of that Hardcastle and Miles were taken up on the Wednesday morning.

Govett speaks of his family and of living in the shop, closing the shop himself and of having his apprentices living in the space as well. The empathy of Govett shows in the record; he clearly is affected by the burglary, which is a high sum of £80. Here is a person who had opened their house to an apprentice and been victimised by it. The modesty of living in the same building with his family and apprentices does not speak to an affluent gentleman, but to a worker.

We can see that the merchant warehouses from the time accrued great capital; however, the smaller-scale producers and workers within the industry, such as Govett, were not as fortunate. As a reminder, Samuel Courtauld owner of Courtauld’s was himself worth £700,000.00 and from Jay’s Mourning Warehouse, William Chickhall Jay accrued £100,000.00, not the producers and workers within the industry.

It was the stores, the profit power-houses that could advertise and exploit grief in powerful ways. Controlling the advertising, the competition between businesses could be fierce, as seen in newspaper advertisements. Larger jewellery manufacturers relied on their own brands to sell products and employed workers to execute on their established styles. Smaller gold and silversmiths had their base cost to honour, as well as living overheads. The front-of-house stores offered a variety of products, with each advertised under their own merits.

JOSEPH’S REPOSITORY

92, BOLD-STREET

The attention of the Nobility, Gentry, and Public is respectfully invited to this

MART OF COMBINED SPLENDOUR AND UTILITY.

THE STOCK

More varied than any other establishment in Liverpool and surpassed by none in the Kingdom, will be found to consist of every article of British and Foreign Manufacture.

LONDON SOLID GOLD JEWELLERY

Of the newest fashion and most elegant designs…

MOURNING AND WEDDING RINGS

HAIR-WORK MADE AND MOUNTED

Joseph’s also featured a large range of cutlery, musical instruments, spectacles, hunting rifles, ironmongery and jewellery repairs. Even in 1839, the competition was fierce, as can be seen in the manner in which Joseph’s markets their store’s wares as the best ‘in the Kingdom’, stocking items from around the world and locally. A gold or silversmith would do well to be part of this business, as their work would be featured and sold.

Jewellers of the 19th century faced high demand for their products, but were largely removed from the purchase process. Stores merchandised with their products, presenting them under their own banner, and took orders from a variety of manufacturers. Jewellers of distinction, however, were able to become their own brand, such as Tiffany & Co. who produced a mourning brooch in 1868.

Smaller gold and silversmiths have only their hallmarks as the artefacts of a business that was. Jewellers maintained competition through the quality of their work and materials, and often also created peripheral metal products, such as watch cases, not singularly mourning jewels. On another front, hair artists experienced different challenges to jewellers; when a material used for mourning art was precious for sentimental reasons, and close to the person who is mourning the personality of the artist using it became far more important.

The ring featured in this article appears courtesy of Kalmar Antiques, who you can find on Instagram, Twitter and on their website.