Ampersand Locket

Love is the intrinsic connection between two people and it is the purpose of a jewel to show this connection in a way that identifies the wearer as being in love. In the 1920s, society had been conditioned by the values of the 19th century and also the Great War, which had changed the socio-political landscape and had a direct impact on fashion and jewellery design. With a change in social values, the representations of sentimentality change. Not that it negates or changes the aspects of love between two people, but the decorations of love change in a way that still are acceptable for wearing.

One of the most fundamentally simple elements of this locket is the absolute simplicity of its design. Using the ampersand in a very Art Nouveau style with gems, this locket simply states that the wearer become part of the jewel itself. As this was worn on the heart, it shows the viewer that the person inside it is part of the person, as the ‘and’ is the connection of need that forms the loving relationship. ‘You and I’ are connected through the simple style, with the photograph being that constant keepsake.

How did this relate to 19th century design and formality? From the late 19th century, there was a popular movement that went against the generational static nature of how fashion was indoctrinated. Queen Victoria, being in perpetual mourning from 1861, was looked to as creating many of the family values of the 19th century, indeed, the monarchy was the key factor in introducing new art and fashion into society. In comparison, George IV had been a patron of the arts and the influence of Continental European culture at the time of the early 19th century cannot be understated. Various styles were competing for dominance in a culture that was adapting to the new techniques of manufacturing in the Industrial Revolution and challenge to political thought through faster methods of communication, such as the steam press. For the first time, the world had been opened to levels of society that did not previously have this advantage. Which is why the art movements, such as the Arts and Crafts style, in the late 19th century were new styles based on nature and not the Court ordained formality of the Rococo Revival style that was so popular in the Victorian era. Jewels were becoming simpler, with the high production and low cost (introduced post 1854 with the Hallmarking Act allowing for alloy production in jewellery) being accessible to all levels of society. With standardisation and simplicity, the messages within jewellery had a great gap between the bespoke and the typical. Anything with tailored symbolism, beyond a written dedication or placement of hairwork/photograph, was a piece that would be from higher society, while catalogue-ordered lockets and ring could be tailored by the individual just by placing a simple sentiment inside. This still remains today; lockets and rings for unions are often seen in catalogues and simply tailored by the jeweller. From this, the artisan jeweller becomes ever more prominent in society.

And…

‘&’ is the most fundamental factor about this locket; its statement is resonant of the 20th century and the messaging of jewellery becoming simple or decorative.

An invention from the 1st century C.E, the ampersand is a corruption of the phrase “and per se and” (the Latin ‘per se’ meaning ‘by/through itself’) and has been placed at the end of the alphabet at the 27th letter. Grown from its Roman cursive derivative and used consecutively since, it was c.1011 that it appeared at the end of the Latin alphabet and 1837 was used in common English.

Its adaption in this locket shows that its use in early 20th century vernacular was popular, as the locket itself is not a bespoke one, but a created and used for its very purpose. Look to the interior photograph as to its personal nature; the lady is not formalised in any way and the picture is taken in a very natural way. From the reverse of the locket, we can see the setting of the jewels in the ampersand and the revealing of the base metal at the hinge. It is a jewel that does utilise the styles popular since the 1890s, in the gypsy setting style of the gems which was quite popular at the time, to resonating the ‘DEAR’ (Diamond, Emerald, Amethyst, Ruby, Sapphire) in the gem configuration. However, the ampersand in this locket is also very stylish for the early 1920s, with the Art Nouveau influence and how its design is morphed into the floral style. It is organic and utilises its simple design in the most fashionable way.

Fidelity

‘And’ relates to fidelity; the union between two people as a consistent connection. But, how does this relate to earlier jewels? There is quite a strong connection between this piece and those of the 18th century for various reasons. From a symbolic perspective, the ‘&’ has the symbolism which is related to the knot, and this symbol was quite prominent in the 17th and 18th centuries.

There are quite a few variations on the knot, one of the more popular being the Celtic knot, which is dated to around 450 CE, which is often referred to as the ‘mystic knot’ or the ‘endless knot’. In this, there is the allusion to birth and rebirth. The expression ‘tying the knot’ is thought to be where the couple had their hands bound in an endless knot as part of the wedding ritual, however, there are several other explanations for this related to the wedding ceremony itself. One of the more enticing explanations from E., M. A. Radford’s The Encyclopedia of Superstitions is that:

“In the seventeenth century, one or two of the bride-favours were always blue. These were knots of coloured ribbons loosely stitched on to the wedding gown, which were plucked off by the guests at the wedding feast, and worn as luck-bringers in the young men’s hats.”

Use of the knot in jewellery was used in the 17th and 18th centuries, with hairwork being woven together and symbolising the union between two people.

For Neoclassical pieces, you can’t go much further than the depiction above that explicitly uses the knot as a primary symbol and sentiment. Look for the knot to appear in many Neoclassical mourning and sentimental depictions, either as an overt statement or relegated to a symbol being held by a central figure or as a flourish depicted in the art. Often, this can be as subtle as a knot painted onto a plinth or tomb.

In hairwork, the knot is quite often displayed with the hairwork of a couple being interwoven and the symbol itself is implied without appearing as the primary focus of the symbolism itself. This is quite common from around the 1780s to the late 19th century in bracelet clasps, brooches, rings and other forms of peripheral jewellery that would house a hair memento.

Then there is the knot as a primary focus, which is very typical in rings and necklaces. The knot is most often seen with the Celtic influences, but many second-half 19th century rings retained a knot motif, often seen as a twist, in various styles and materials. Knots in necklaces were also popular from the 1860s onwards, with the necklace itself twisting into a knot around the chest. Chains were also tied into the concept of the knot, used in bracelets, necklaces, links in fob chains and other items as well.

In the 19th century, mourning and sentimentality were part of the family structure, with mourning periods being imposed by Court. The affectations of mourning and sentimentality were a cultural necessary; they needed to be adhered to for presentation of the family within society. From this, Burial Societies saw a massive rise in revenue, as people of all levels of society would give their money for a decent burial that would not shame their family. Jewellery was a necessity, as it was part of the Court mandated mourning period and also just a matter of social proprietary for showing relationship status.

Mass produced jewels came from this, but with higher production, lower detail and ubiquitous sentiment was normal. Hairwork, once prominent in 17th and 18th century societies, was pushed inside lockets and underneath rings, rather than being the centrepiece to the jewel. Note the following swivel/locket rings and follow that back to their predecessors:

Connecting two people together in jewellery symbolism was often the function of allegorical symbolism (when seen beyond the ‘knot’). Love birds were often the most popular in the 18th century Neoclassical depictions and show the unity between lovers. As this locket has the ampersand and the interior dedication to the loved one, then we can see the same narrative in jewellery. The connection is more immediate, as the loved one has a direct interpretation in the photograph, which was obviously not possible in the 18th century. Much design is resonant to its culture and construction, hence the meaning of fidelity through the broader spectrum of the locket/photograph combination, while earlier pieces and prominent styles were due to their cultural influences.

To investigate more, one needs to look upon the styles of the time which could change sentimental perceptions. Was it money, social change that bought this style about? the catalyst is within several factors leading to the 1920s…

Leading to The 1920s

From 1900, there was a significant split in jewellery styles. Court-worn jewels were still based around the Rococo Revival style and using highly privileged, material-based gems, such as diamonds. This was normal around European Courts and remained consistent from the 19th century. In Europe, the organic influence of Art Nouveau and its use of coloured gems and enamel became popular. The Arts and Crafts movement flourished in Britain as a response to mechanisation; bringing back a return to traditional crafts. This remained consistent up to the beginning of the First World War.

South African diamonds produced 90% of the world’s diamonds in 1890, with a slight interruption by the Boer War in 1899-1902. White gold and platinum were used to enhance the look of the diamond, leading this to become one of the most popular styles in fashion for the time. Its influence can be seen today, with ‘white’ jewellery being more popular than the silver influence of the 1880s simply because diamonds were enhanced by the white colouring of the metal and diamonds themselves were cheaper and more accessible.

‘Garland’ style jewellery was made popular by Cartier, which referenced Louis XVI style, featuring garlands of laurel leaves, lace patterns, ribbon bows and tassels. This style resonated throughout Europe and America, but only in high wealth. Art Deco had its origins in this style, with Boucheron, Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels all experimenting this style, but adding gems and exploring its development.

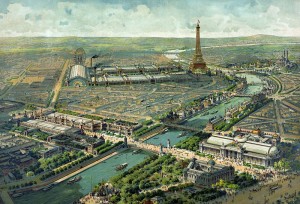

It was the financiers who made this development possible. At a time when new wealth could define new styles, going beyond the previously established family-based old money, Americans began to spend their money in Paris, leading to the rise in jewellery production houses and their proliferation. Tiffany & Co. developed by this money and presented their quality work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. Notably, their contribution to jewellery development was the Tiffany Setting in 1886; a diamond setting above a ring which lets in as much light as possible to the stone. René Lalique, whose influence to Art Nouveau is exponential, was awarded a Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition, leading to the popularity of delicate, organic styles in jewellery design and development. Methods, such as the Plique-à-jour enamel work (meaning ‘letting in the light’), were fundamental in how jewellery design was reacting to the previously consistent styles that had represented the late 19th century.

This is why the Paris Exhibition was so fundamental in disseminating new styles throughout mainstream culture. Wealth from America and driven by industry was empowering artists to go beyond the Court/aristocratic styles that hadn’t had the early 19th century monetary drive and lockets such as this ampersand piece could thrive. Look to the design of this piece; the Nouveau elements, from the organic curve to the floral outcrops.

Post War Mourning & Sentimentality and Photography

The decline of the mourning and sentimental industries was not exclusively ‘mourning’ related, but an actual change in fashion and social taste. How to present sentimentality and love in a public forum through a jewel was very different in the post 1901 environment than it had been since 1861. Two generations had passed under a very static monarchy, which originally had been the cultural impetus for fashion and art. Society would look to the monarchy for various elements to adapt, the most noteworthy being George IV, but Queen Victoria had established the ‘ideal’ family unit under a Christian value system and then fallen into perpetual mourning. Despite the underpinning realities which may contradict this, it was then, and still remains, a value system that Western cultures still use today. Everything from the establishment of wedding ritual to Christmas rituals and their surrounding affectations are built from the 1840s, yet there was a rebellion in society that needed to create its own style and movement to break apart from what was considered a rigid perception of mainstream fashion. This change came about in the 1890s.

Throughout the post 1880s decline, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure. While this perception is very affecting to mourning, the sentimental industry and its production of jewels as tokens of love were changing rapidly. There were art movements, such as the Arts and Crafts movement, which built upon the ‘natural’ elements of beauty and design to be interpreted in architecture and industrial design. This was a counter-reaction to the industry that had dominated 19th century life, by moving back to organic styles. This is much the same as the Rococo movement in the early 18th century, which reacted against the dominant Baroque styles with organic flourishes. This, in conjunction with the Enlightenment, led to new perceptions of the self in the Neoclassical movement and in the late 19th century, we see the same revolution in cultural style.

Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 created the catalyst which led to the new generations establishing their own styles as the new social revolution. From an inward-out perspective, the English looked to France and America as being the leaders of influence in style and these adaptations had a massive impact on jewels of the time.

But that is not to say that jewels of the 19th century ceased to have their impact. The gypsy-set jewels of the late 19th century were still popular, as well as many of the existing styles which could be purchased in catalogues. Hairwork and mourning jewels suffered, while a new Romantic movement led to miniature portraits, love tokens (heart shapes, particularly) and narrow brooches with simple and direct symbols set with gems. The difference here is that the Edwardian jewels were built around the artist and designer. Jewels that were a step beyond the catalogue-bought styles focused upon new artists, such as René Lalique, and the rise of competing art movements to represent these styles in jewels.

Even for World War I, with an estimated thirty-seven million casualties, a mourning industry to rekindle the previous generation, did not happen. Different sentimental elements, such as the giving of a watch chain to wear as a necklace, became sentimental keepsakes, rather than a proper dedication in a ring.

Photography is the final key factor in the depiction of the self. Its impact on jewellery design cannot be understated, as the capturing of an image of a loved one overcame the capturing of a piece of that loved one in hairwork. Much of this change is why the perception of having the hair of a loved one in a jewel is considered morbid today. Why have hair when a photograph was nearly instantaneous and within the budget of a working class individual? Better technologies led to photographs having smaller sizes and that led to smaller jewels being constructed around this form factor. In this jewel, we see the elements of the heart and the photography combined with a cameo of the female denoting a loving piece for its time.

And That is All

Here, we see the honest truth of sentimentality in the 20th century. As a piece, which is assumed to be dated December 25th, 1922, as seen by the reverse of the photograph, we have a clear identity to prescribe to the piece. Was it given as a sentimental token at Christmas time? Was it a piece that was randomly assembled? Was it created at an earlier time and appropriated with the photograph? All these questions are assumptions, but what can be sure is that it was worn for the very aspect of love; the wear to the piece justifies this. As resonant today as the day it was created, this locket is a beautiful testament to time and one made during an era which has defined our perceptions of love today.