Agadez: The Tuareg and Memorial Jewellery

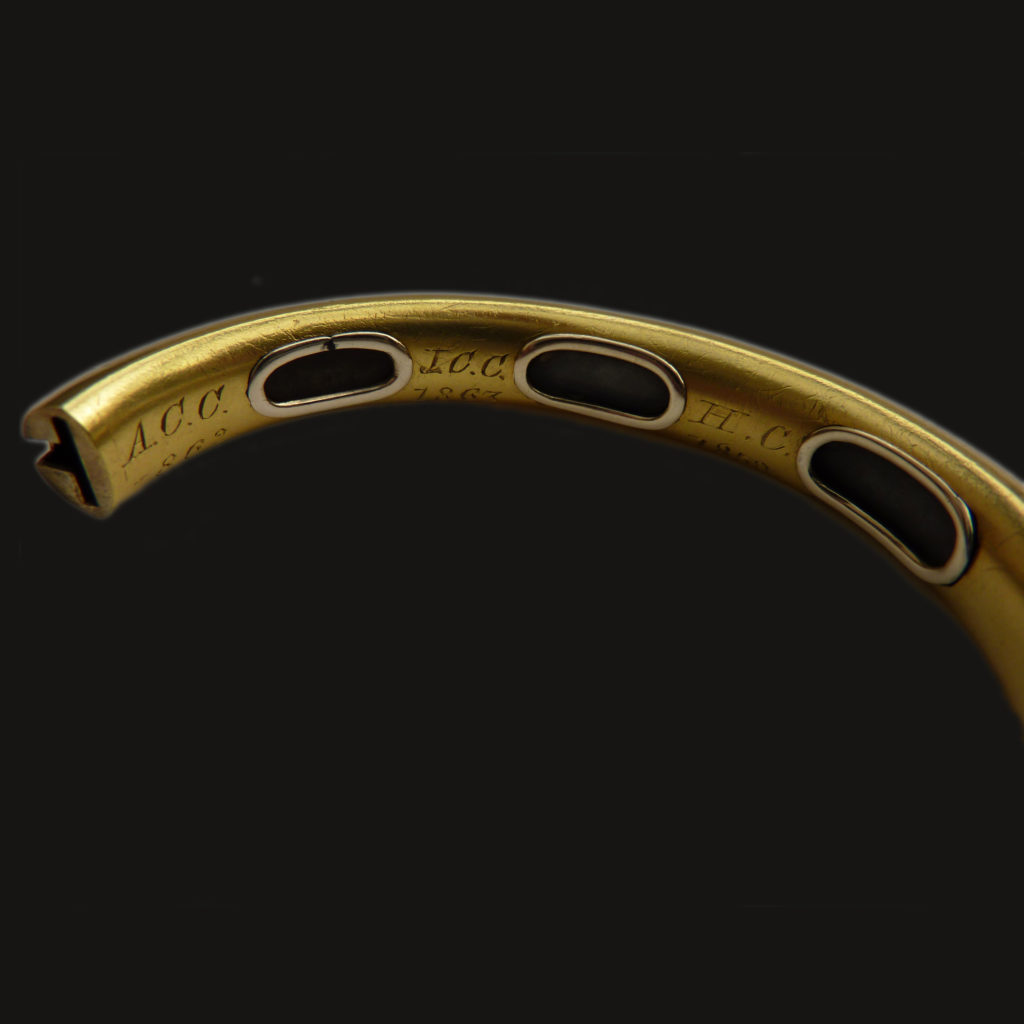

These bracelets, replicated by Will Francis, open up a different element to memorial jewellery, one that developed in a different culture than those of the industry we know today. These jewels are based upon the Saharan based Tuareg people and their memorial and sentimental culture.

Of note in these bracelets is the cross symbolism and how the other design elements relate to the jewel. Much of the Tuareg jewellery is relative to personal experience, so focusing on the smaller elements are important.

The Tuareg

A nomadic culture based in the Sahara of Northern Africa, the Tuareg were organised into tribes during the 19th century, with their labelling being an external one; surrounding cultures identifying them based upon their appearance, language or region, such as their title of “The Blue People” due to the indigo colour of their veils and the colour of the dye on the skin. From the mid 20th century, the region was classified into political areas and colonised by the French, spurring forth conflict and Berberism. Berberism is a form of nationalism and the Tuareg identify with this, as their cultural identity is separate from the politically represented ethnicity. A tribe would traditionally consist of thirty to one hundred family members, keeping cattle, chicken, camels and goats.

The jewellery of the Tuareg is close to their representation of the self. Jewels that identify an individual with religion, maturity and memorial objects are part of the personal affectation. Designs in the jewels are subjective to the wearer, with elements of personal stories being etched into the jewel. Silver is the most popular material, with gold being a superstitiously feared material. A jeweller would be born into their role, rather than develop into one, as the family lineage was carried on. This was so specific that the jewellers even developed their own dialect, called Ténet. As jewels are items of wealth and status in Western cultures, the sentimentality of a jewel needs to be factored into how such an item can be so prominent in a culture.

As written in Sarahan Arts, the cost is as follows:

A tchérot amulet pendant = 1 young camel

Two rings = one kid goat

A small padlock = one goat

A large padlock = two goats

A dagine style bracelet = two goats

A veil weight / padlock key = one goat

There is a transaction system that allows for status based on social utility; a productive farmer could purchase a jewel through goods and services. Compared to the Western variation, systems of wealth and social status within a monarchy or political hierarchy would denote what a person could wear and how allowable that was within society.

Southern Cross / “Son, I give you the four directions, as no one knows where your path will end.”

As an element of decoration, the cross has its basis in nature, as well as the identification that Western culture has placed upon it through the Christian definition. The cross roads, being a point where a decision is made based upon direction, is the analogy of a life choice. With this choice comes the jewel that was passed from father to son at puberty, being a talisman of virility. As a nomadic culture, the Tuareg look upon the crossroads as being four directions of the life decision. This is also represented in the pommel of their camel’s saddle, with the four directions leading the rider into their fate.

Relation to Western Memorial Culture

The Maltese Cross (or Amalfi) is an unusual symbol. It has quite a lot of history behind it and its connections to the cross and how we see it in jewellery usage vary from the accurate appraisal to the incorrect usage as a terminology to refer to similarly styled pieces. To understand why this is so, we need to look at the Maltese Cross itself, what it represents, then look at the Gothic Revival period and then take a walk up to Golgotha with the cross itself.

For a symbol that has quite a specific title and, one would think, a specific purpose, the Maltese Cross is seen cross-culturally in everyday life. The symbol itself was first depicted (or at least, recorded) on currency c.1567, being the 2 and and 4 Tarì Copper coins. The Tarì was used in Sicily, Malta and southern parts of Italy c.913-1859 and stems from Muslim origin and manufacture, as a currency it was quite popular. It was the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, Jean de la Vallette-Parisot (c.1494-1568 / Grand Master from 1557-1658) under whose leadership provided the minting of these coins, hence the relation back to the nature of the cross as a Christian symbol and also its identification as Maltese.

Characteristics of the Cross

We must now reflect upon the style of the cross and its characteristics. What is it about this cross that seems to capture the imagination enough so that it is such a popular symbol in so many of our day to day lifestyle? Firstly, note the indentations on the points of the cross and how they form an arrowhead shape with eight points. This is incredibly important to distinctively spot a Maltese Cross in our jewellery collecting, whereas many of the pieces popular in the early 19th century are based upon the Cross Formée (stemming from the subgroup of Cross pattée / St George Cross). Naturally, the cross as a motif is has its Christian basis, however, the Knights Hospitaller evolved the design, which stemmed from Crusader interpretations for other Christian warrior identifiers.

Symbolism of the Cross

Reasons for the mistaking of the Maltese Cross for its use in jewellery not only stem from its characteristics. The symbolism behind it, relating to piety, loyalty, generosity, bravery, glory/honour, contempt of death, helpfulness towards poor/sick, respect for the Church are all ideal reasons for why a piece of jewellery would be constructed and worn. In terms of symbolism, many of the pieces we have in our collections don’t have this level of detail. These are the reasons why the cross is so widely used in coats of arms around the world (namely Australia), aviation, medical services (particularly ambulance), sporting clubs and various other institutions. Bravery, loyalty, piety; all the things which construct the foundations for a respectable service or unity of like-minded individuals. Hence, this is why we see the Maltese Cross so frequently in society. It is produced and worn as an item of dress in uniforms, so it becomes more than simply a motif on a flag, it becomes physical and much of this has to do with why our jewellery collections have pieces referred to as the Maltese Cross, when this is a symbol that splintered from what much of us understand or collect.

Relation to Jewellery

The first half of the 19th century saw such a radical swing away from the culture that had preceded it since the second half of the 18th century. Christian values were starting to rebel against the seeming decadence of the Neoclassical society and art around, or at least reclaim the religious underpinnings that had dissolved when society started to merge into a more humanist view of the world. Where the symbols of death had been obvious in earlier jewellery of the 17th century and early 18th, figures of personal scenes of people in mourning were typical. The cross as a symbol of final judgement was almost anachronistic in its formal style and when used, relegated to a secondary symbol in many of these pieces. It was the person, front and centre, depicted next to an urn or tomb, weeping or looking away to watch the soul depart.

And then we have the Gothic Revival. The symbols that pushed their way back into mainstream society were not simply stark and bold as a sudden revolution back to Christian values, but they infused with the current mainstream style and blended the classic Christian motifs with the Neoclassical designs to produce pieces like the above. And what do we have there? You might think that it is the Maltese Cross, but it is the Cross Formée (note the lack of indented points), used as a way to reclaim the same ideological identifier as the Crusaders who developed this style of cross themselves. The Gothic Revival was capitalising on literally ‘reviving’ the Gothic period, its art and simplistic style. Here is a cross being re-appropriated for its time. A cross that was developed between c.1144-1271 is now becoming mainstream fashion. And while it isn’t the simple grand statement of a straight cross, it has enough style and flourish to be consistent with an opulent time in art. Notice how this cross is encrusted with foiled flat topped almandine garnets with glazed locket compartments, displaying hairwork and the names ‘Marmaduke Hart Hart’, ‘Agustus Tulte’, ‘Caroline Gordon’ and ‘Ja(me)s Peard Ley’. The humanist nature of the piece is not lost in any way, it’s beautiful, decorative, displays the dedication of the people who were loved and still has all the Christian symbolism that one would expect from a pious household. So, just because the Gothic Revival meant a swing back to Christian ideas, it didn’t dissolve what had come before.

This was a style that persisted into the 1840s, which was followed heavily by the return to the stolid cross itself. As you can see from the piece above, it’s a prime example of an agate Gothic Revival cross in memorial jewellery, with the heavy gold-world reminiscent of the Rococo style and dedication of hairwork and name. But pieces like this are still sold today under the impression of a Maltese Cross, when that has its dedicated eight points.

Here is where we need to consider one again the symbols at play. The Maltese Cross has its aforementioned symbolism, but here we have a stylised cross and it is a symbol that, as it became more and more adapted into the lexicon of an official cross for countries and institutions, there wasn’t the demand for its seemingly established symbolism to represent the self. However, regular crucifixes worked in the same capacity as one would expect from this style, so why not simply use a crucifix in the latter 19th century?

At the Crossroads

A culture that wears a jewel for its meaning, be it the relation to the Qur’an, a rite of passage for a male reaching puberty or for the purposes of remembering a loved one has a jewel which resonates just as strongly as any from another culture. The symbols and meaning of a jewel are the primary reason why they were created and these affectations keep us attached to our surroundings and loved ones. An established society with imposed meanings around symbols and a monarchy to dictate what they represent are simply a formalisation of what the inner nature needs to trigger a memory, while bracelets like these are quite individual.

Courtesy: Will Francis