A Victorian Hair Bracelet for Bessie

Hair is a remarkable material for remembrance and love. While not considered the token of friendship today which it was during the 19th century, hair is uniquely individual and a stark reminder of the person you miss. From the colour, curl or density of the hair, it is a trigger to the memory of a loved one.

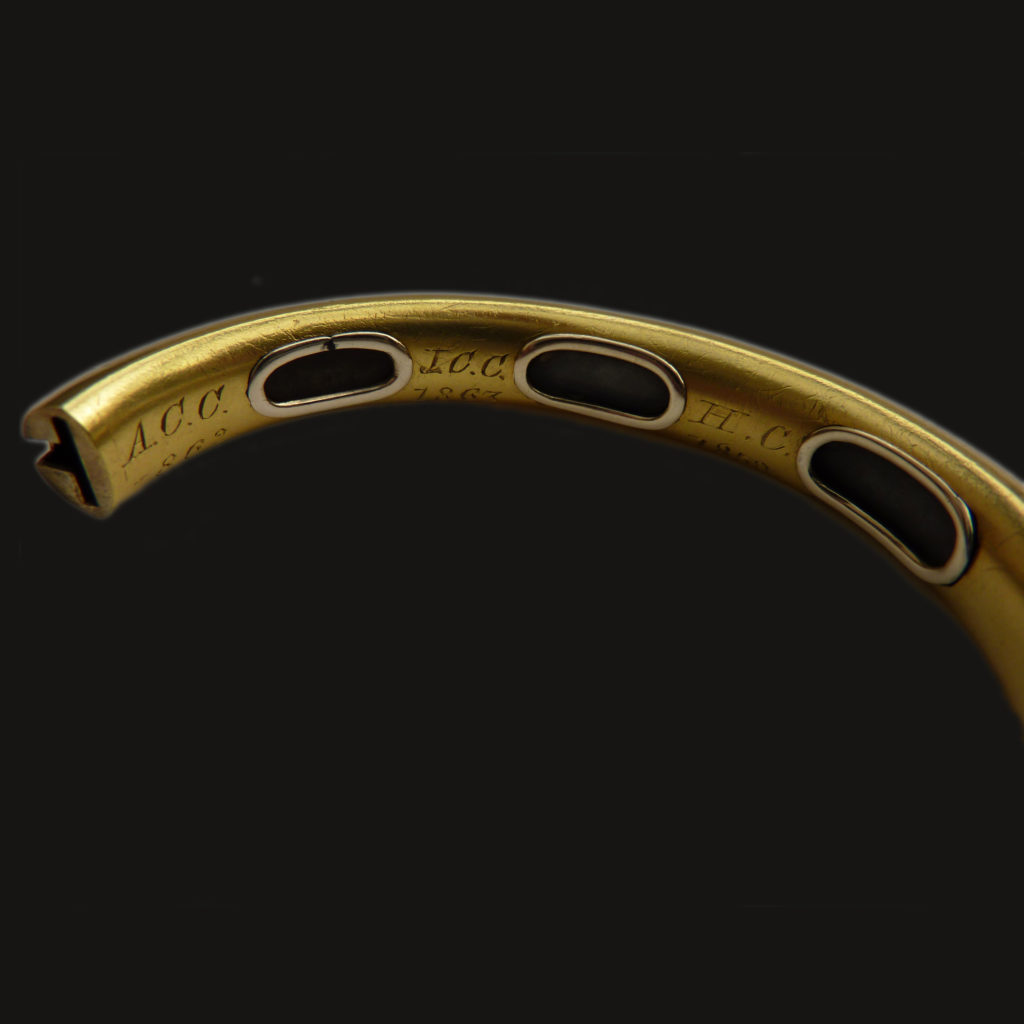

In this bracelet, Bessie is remembered by a loved one, presumably a lady, in a very opulent bracelet that is a superb example of mid 19th century sentimentality. Bracelet clasps of the latter 19th century tend to fluctuate between highly embellished, where they can be identified from the 1854-1870 era, and more simple designs from the 1870s-1890s.

Of note are the hinged shoulders of the clasp and the embellished designs of the shoulders where the hair is tied into, as these lead into the main design focus, which is actually a locket with a twist of hair inside. Often with sentimental bracelets of this style, there are several kinds of hair donated by loved ones and interwoven, so that the bracelet itself becomes a union of several different people.

In this bracelet, there is a singular coloured hair, and as hair was colour-matched from the European Continent, discerning anything more about the hair is not possible. Here, the brown colour is ubiquitous across the bracelet and the name on the front of the locket opening is a signifier for whom the bracelet was dedicated to.

This bracelet opens many doors about its history; from the design of the Rococo elements, to the size of the piece and the development of sentimental fashion in the 19th century. Let’s take a look at several of these elements and discover why its development came from a tighter regulation of social presentation and higher global production.

Hallmarking Act & Fashion

The Hallmarking Act of 1854 saw the allowance of alloys used for jewellery production. From a perspective of fashion, this was exponential, as dresses were becoming more voluminous with large crinolines and wider sleeves. Jewellery which was constructed from heavier metals was not practical for daily wear, as larger styles could not support the fashion in which they would be displayed. Compare this bracelet with one from the early 19th century:

This bracelet shows all the signs of the Neoclassical era, which had higher waistlines and no rigid bodice or hooped skirt to contort the image of the body. Shape became more important, with smaller styles in oval and rectangular shapes, holding hair under glass and commonly being surrounded by pearls or other gems.Bracelets were commonly strung with pearls or hair; the subject of pearls in the 18th century can be read about here.

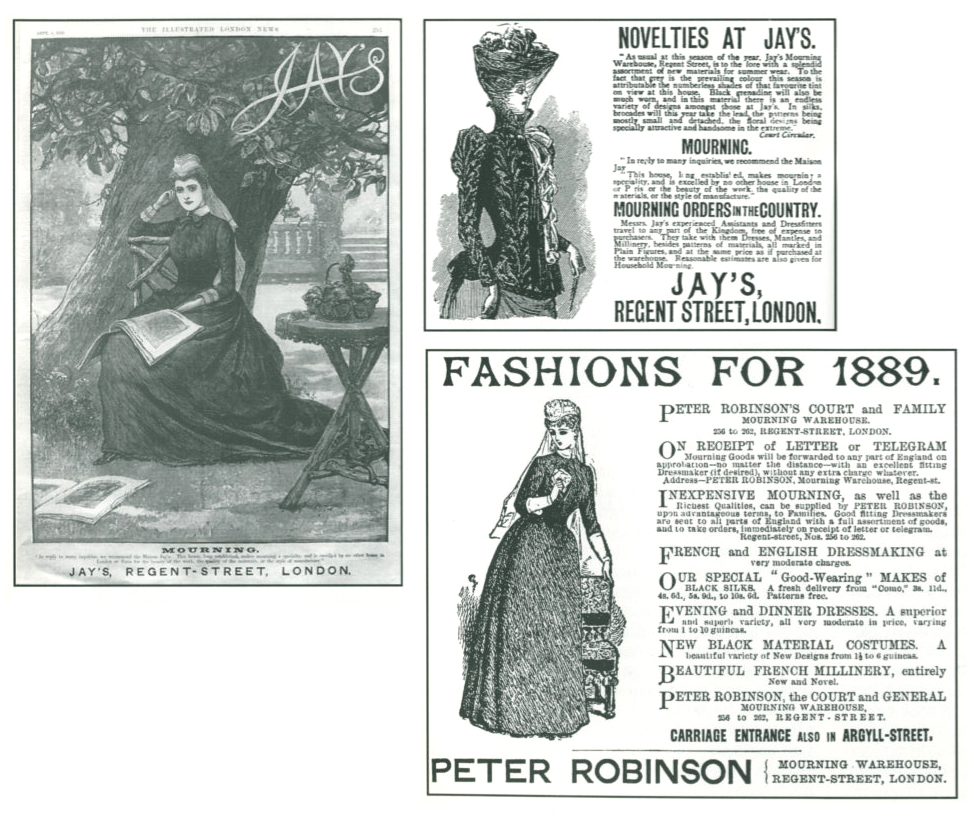

Mourning fashion and sentimental fashion are linked. The act of the memory for a loved one is engrained in the industry that developed mourning culture and mandated from the monarchy down. In the same vein as mourning jewels, sentimental jewels were not always an item that would be worn more than a handful of occasions, as they were kept for their value as a token of love. Many of these pieces have remained in perfect condition, as produced pieces would be stored away and not worn, but kept as a keepsake for the loved one. Several may have been produced for one deceased person, with the bequeathment having funds in the will to produce enough mourning jewels for female family members. This comes from the requirement of mourning being a necessity within the family to present themselves in mourning. A person would work their lives and give a portion of their wages to a Burial Society for the benefit of a proper funeral and the trappings of mourning to be provided for the family.

Mourning regulation went through different permeations in the 19th century and became longer and more rigid. It was on the 7th of November, 1817 upon the death of Princess Charlotte that Lord Chamberlain ordered official Court mourning: ‘the Ladies to wear black bombazines, plain muslins or long lawn crape hoods, shammy shoes and gloves and crape fans. The Gentlemen to wear black cloth without buttons on the sleeves or pockets, plain muslin or long lawn cravats and weepers [white cuffs] shammy shoes and gloves, crape hatbands and black swords and buckles.’ For undress wear, dark grey frock coats were permissible. The Second stage was decreed two months later, with the allowance of black silk fabric, fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black shoes, fans and tippets, white necklaces and earrings, grey or white lusterings, damasks or tabbies and lightweight silks for undress wear.

Men’s dress was unchanged. The third stage allowed women to wear black silk and velvet, coloured buttons, fans and tippets and plain white, silver or gold combination coloured stuff with black ribbons. Men could wear white, gold or silver brocaded waistcoats with black suits. The rules set by Lord Chamberlain crossed Europe, the United States (from the 1860s / 70s) and colonial territories, but Court mourning was longer than General mourning. General mourning was growing in popularity due to the accessibility of mourning costume and the cost.

For the stages of mourning, one of the most important factors is colour. For example, turquoise was often used as a during the half half morning stage, post Third Stage (or Ordinary stage) as a mourning material, with its influx of colour. This stage was introduced after twenty-one months, involving the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted. Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months.

The English Woman’s Domestic Magazine stated that ‘many widows never put on their colours again’ and this was quite a statement for the identity of the woman, which was held under the veil of mourning and family symbolism for the rest of her life. While mourning fashion relates closely to sentimental affectations, the sentimental value of a jewel did not mean that a person was required to wear a dress of love dedication. While a white wedding is considered the formal way to be married, with white itself having its virtues in purity and virginity, a hair bracelet for sentimental reasons could be worn in daily fashion and was not locked into any personal statement otherwise.

Tokens of Affection in the 19th Century

Hairworking, as a practice, was something that could be done in the home or in a proper profession. Indeed, it was one of the earliest, early-modern, female professions within an industry, as women would be employed to weave hair. Mark Campbell’s excellent ‘The Art of Hair Work’ (1875) is a testament to how hair weaving could be accomplished as a household art and one that could also replicate the professional hair weaver. Designs and styles for woven hair could be chosen from a catalogue and the hair given to the jeweller for weaving. By the 19th century, the custom of hairwork had become ingrained in popular culture of the time, spanning Europe to America, and the hairworking industry hit its peak. The popularity of hairwork and its move from country to country was not a singular event, but reflects more upon society of the time. Hairworking industries along the Continent have their roots in hairwork as a folk art and female amateurs practicing the art in their home. Because of this, the popularity spread through Europe, especially prominent in France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and even across to Bohemia.

The American hairwork industry evolved in its own right, growing in prominence over the 19th century (particularly during the Civil War) and still exists in a small capacity even today. Hairwork lends itself easily to other forms of household practices, such as stitching and weaving, which makes it transcend many cultural barriers, and the sentimentality of it only adds to its necessity.

As a mourning device, hairwork is a vital memorial statement within the family. Coupled with household art in the 18th to early 20th centuries, hairwork was another way to display the loved one’s hair. Samplers and hairwork memorials are prime examples of hairwork as a folk art. Samplers vary from country to country, as do hairwork memorials, which can take the shape of flowers within wreaths, crosses and a variety of other memorial symbols. Especially in America, hair wreaths were a “popular parlor pastime like many other crafts” for women. German and Swiss hairwork memorials were often quite different from the American, as there was a greater use of depth and colour. French were more palette-worked (cut-work and sepia) and more darker, while German and Swiss hair is fairer with greater use of watercolour. German hair memorials often used two panes of glass with one being a painted background and the foreground applied hairwork. Again, regional variation within the hairwork paradigm is the prerogative of the creator or evolution within the household.

Royalty was still the focus of the hairworking fashion for the 19th century, spanning through the Georgian and finding renewed popularity in the Victorian age. Fashion was often dictated by royalty, and it was royalty which largely perpetuated the popularity of memorial jewellery. When hairwork was worn by anyone of note, fashion often followed, as seen in the previous account of Queen Henrietta Maria and the use of memorial jewellery for Charles I during the Restoration period. In the 19th century, the executor of George IV’s estate, the Duke of Wellington, told Charles Greville that amongst George IV’s possessions he found “a prodigious quantity of hair – women’s hair – all colours and lengths, some locks with powder and pomatum still sticking to them”. From around 1830, this quote from Wellington displays the extent to which hairwork was embraced by mainstream culture at the time. An extraordinary quantity of hair kept by George IV implies its importance as a keepsake even at the upper levels of society.

Queen Victoria is one of the most popular figures regarding the rise of the mourning industry and the increasing strength of the hairworking industry. Victoria’s fastidious sentimental nature and her clinging to keepsakes can be seen in her putting Albert’s hair in brooches, bracelets and other forms of jewellery after his death. Keeping hair was as important as giving, due to the nature of the sentiment. Empress Eugenie of France was “was touched to tears when I gave her a bracelet with my hair”, wrote Queen Victoria upon presenting the bracelet. Though these instances of hairwork in royalty show how popular hairwork was, they are from an English perspective. Other countries and cultures developed their own hairworking industry that permeated through mainstream society of the 19th century.

In the Paris Exhibition of 1855, a life-size portrait of Queen Victoria was created, a worthwhile homage to a queen who appreciated the sentiment of hairwork so much. Indeed, with such a cultural importance on the value of hair as a material, the French were the epitome of style and to use such a material in a gesture shows just how widespread hair was used in mainstream fashion. In 1858, fashion magazine La Belle Assemblè referred to the French hairwork artist Limmonièr in a revolutionary light. La Belle Assemblè expands on the association with hairwork as a sentimental device and identifies it as a jewellery construction material in its own right, not simply “in which some beloved tress or precious curl is entwined”.

“(Old styles) gave the appearance of having been designed from a ‘mortuary tablet’. Have we not all met ladies wearing as a brooch, by way of loving remembrance, a tomb between two willow trees formed of the hair of the individual from whom their crêpe was worn, and which from its very nature must be laid aside with it? But the new hair jewelry made by Limmonièr is an ornament for all times and places. He expands it into a broad ribbon as a bracelet and fastens it with a forget-me-not in turquoise and brilliants; weaves it into chains for the neck, the flacon, or the fan; makes it into a medallion, or leaves and flowers; and of these last the most beautiful specimens I have seen have been formed of the saintly white hair of age. This he converts into orange flowers, white roses, chrysanthemum and most charming of all, clusters of lily-of-the-valley.”

The Mid 19th Century and Jewellery

Innovation led by Albert, Prince Consort cannot be understated for its values and impact upon society. The Great Exhibition of 1851 came about during a time of European and Latin American economic turmoil in 1848, leading to revolutions following the rise of nationalism. Albert’s dedication towards acknowledging the underprivileged and offering financial and educational assistance was an incredibly bold stance for the time, particularly when his family in Europe was being threatened.

Since 1843, Albert was President of the Society of Arts, which, from its annual exhibition, became the basis for the Great Exhibition. Based in Hyde Park within The Crystal Palace, the value of science, art and industry became a matter of pride for British society, which is a progressive step and one that shows the great innovation of Albert, himself. As a counter to revolution, The Great Exhibition stood fast and as a catalyst for art and innovation, the impact upon jewellery design that was revealed through new techniques of metallurgy and style resonated back through society.

The 1850s led much of this standardisation, with the family elements that were instilled by Victoria and Albert becoming popular in terms of literature and fashion. New challenges, such as Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, threatened the Christian family that had been established by Victoria and Albert, but fashion was still permeable. Romanticism flourished in literature and art, notably by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late 1840s. Looking towards medieval culture for inspiration and harshly turning against realism, many of the mourning and sentimental symbols that are common today in jewellery and funerary art were carried through by their use in art.

Within literature, one must not look past Charles Dickens for the usage of Victorian sensibilities and values within his writing. Albert died in 1861, effectively locking Victoria in a period of perpetual mourning. The effect of this was felt within jewellery design, leading to a very static period for jewellery design in the remaining century. Bolder style was in its element during the 1860s. This can be attributed to the mourning of Queen Victoria from 1861, but also tells of the evolution in costume and everyday dress. The larger styles of the mid-Victorian era had taken hold, with female fashion becoming larger and the jewels needed to adapt.

By the latter century, costume and function were tightly connected for women. Dresses of separate bodice and skirt were worn in bombazine covered in crape. Underwear was often white chemises, drawers and under petticoats slotted with black ribbon. Black caps, crape trimmed bonnets, and long veils. First mourning lasted one year and a day, outdoor garments for this would be shown by the plainness and amount of crape, jet jewellery was permitted. After one year and a day, Second stage was introduced. This involved less crape and its application to bonnets and dresses became more elaborate. It was frowned upon if this period was entered into too quickly and it lasted nine months in all. The Third stage (or Ordinary stage), introduced after twenty-one months, involves the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted.

Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months.

The English Woman’s Domestic Magazine stated that ‘many widows never put on their colours again’ and this was quite a statement for the identity of the woman, which was held under the veil of mourning and family symbolism for the rest of her life.

Hats, shawls, mantles, gloves, shoes, fans all changed during mid century, and pagoda sleeves from 1850-70 were fashionable, designed to be stitched to the outer sleeve to cover modesty from the lower arm and wrist. Wide skirts from the 1850s-70s, tie back fashions of the late 1870s and the ‘S-bend’ look of the early 1900s all were adapted to mourning fashion, without a clear definition of difference between them. Throughout the post 1880s decline, in the 1890s, women would wear their veils at the back of the head only, showing hair beneath bonnets at the front for first stage mourning. This defiance was quite bold and marked a large turning point for mourning structure.

In a Name

Bessie is written across the facia of the locket clasp, within ribbon and Rococo motifs. This, in itself, is the key element of the bracelet that brings it above being considered a ‘sentimental’ bracelet of its time. Having a name attached to a memorial token, for love or death, is important. This is the focus that makes the collector identify with an individual.

For its time, this is a statement that goes beyond the standard ‘In Memory Of’ or ‘REGARD’; this is for a person that is proudly worn over the cuff on the wrist. During the 19th century, there was a move towards the standard sentimental messaging, from the previous bespoke messages of the Neoclasscial period. In the previous period, statements such as ‘Not Lost But Gone Before’ or ’Sacred Will I keep Thy Dear Remains’ are quite close to the person who had commissioned the jewel. These could be tailored for a specific person inside a pre-designed setting:

It was the Gothic Revival period that had effectively pushed sentimental messaging into the interior of a jewel, written inside and hidden from external view. As this was the standard made popular by Queen Victoria and ingrained within society and industry by 1861 through Victoria’s move to perpetual mourning after the death of Albert, sentimental jewels are more obvious with their name dedication written outside the jewel, rather than inside.

Of course, the normal bespoke pieces existed and pieces of higher cost were created, but ordering a jewel from a catalogue with standard mourning/sentimental statements made it easier to etch a dedication inside/under a jewel.

Monograms in shields are more typical of the latter 19th century, as the style of etching had a place to be. A token of affection could be worn externally, with a blank canvas for the jeweller to put their required statement on top.

During this time, it is important to understand the peripheral mourning and sentimental items that could be more bespoke than an expensive jewel. Photography and ephemera were far cheaper, with people being able to give a highly decorated card to a loved one with a photograph or loving sentiment. These could be carried inside compacts and taken with someone travelling. Jewels, in this instance, become more of a fundamental statement of affection, as they are not always hidden and denote the status of the wearer.

For Bessie

There are so many elements to this bracelet that a single narrative would not to it justice. From the following links below, I will feature several jewels to discover and learn more about. These will identify this bracelet closer to its construction and contemporary jewels.

Value in jewellery is not about the weight of its gold or the lustre of its gem. It is about why it was worn and why it was made. Anything that requires thought means inspiration. Inspiration born of love and ideals are elements that create families and these are what carries the memory of a person alive forever. A jewel, to be worn by a person, is intimate. Jewellery made of hair even more so, as this is literally a piece of the person that becomes fashion. Bessie’s bracelet will resonate on and still carry that message through time, with its elegance, grace and ability to always show who she was.

Further Reading

> A History of Hairworking

> Art of Hairwork 1: Victorian Hairwork Fob Chain With Serpent Clasp

> Art of Hairwork 2: Directions for New Beginners

> Art of Hairwork 3: Victorian Hairwork Fob Chain With Locket

> Art of Hairwork 4: Victorian Hairwork Fob Chain With Acorn Charms

> Art of Hairwork 5: Victorian Hairwork Fob Chain With Black Enamel Fittings