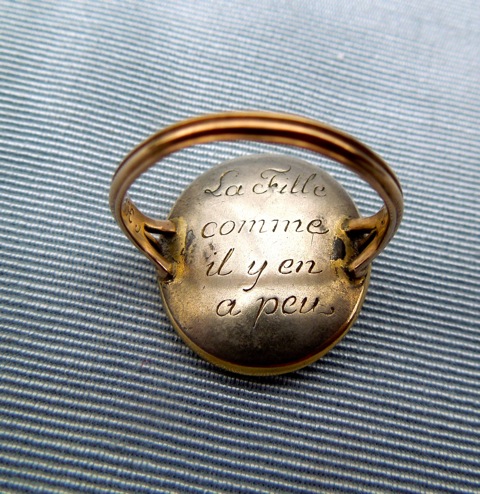

A Mourning Tour: “A souvenir (memory) of a daughter like no other” Coronet Crystal Ring

There is a delicate sentimentality in Stuart period jewels which reflect a burgeoning sense of love between two people. Attainable jewels of fashion could be manufactured with loving dedications through a sharing of jewellery manufacturing techniques and greater government stabilisation, leading to investment in industrial manufacture.

In the use of cyphers and monograms, gold wire was commonly used to display these proud sentiments. Often placed underneath faceted crystal and placed on top of woven hair, material or vellum, this period of the late 17th and early 18th centuries is easy to identify. Most common of all were rings and ribbon slides, worn at the hair or wrist for slides and prominent fingers for the rings. There was nowhere with which jewels like this could not be seen; they were not relegating the personal nature of the person to the underside of the ring or slide, they were displaying it on top. In contrast, 19th century jewels would display the sentiment on the outside and the individual on the inside. If this ring was worn in public, it would have been a pronounced statement, indeed.

Underneath the ring is where the the connection between the two are. Connecting the sentiment above to the initials, and this is where the ring takes on its own personality. Roughly written as:

Le Souvenir en elt précieux

La Fille comme il y en a peu

Connects the piece to a little girl, or daughter, making the ring completely sentimental throughout the band and the reverse of the bezel. Having both the sentiment written into the reverse of the piece and having it carry around through to the band shows that this piece was completely bespoke and never altered. Quite commonly, particularly with pieces which have a monogram that is the same as a someone who is looking to re-appropriate a jewel, pieces can be used by subsequent generations, while polishing out any sentiment to the reverse of the bezel. Here, the piece is pristine, with little wear from when it was created.

It speaks to many various influences of its time, showing the importance of ecclesiastical change within 17th and 18th century European society, social mobility and the display of fashion to represent the self and the family in public . All of these elements relate to identity. Gathering wealth to improve the status of family within society is connected to education and the adaption of new skills. These new skills could not be adapted if it wasn’t for a great influx of intellectual challenge during the early modern era and the Enlightenment. Development of technologies and industry allowed for rings such as these to be produced and worn in society, which had not been an accessible commodity to the greater society.

Let’s look to similar jewels and fashion in order to understand what the culture and values were like during the time that this ring was created, in order to discover why it was designed and worn as a token of love and affection.

Influences

Since 1066, the use of Anglo-Norman French was infused within English society, though never an official language. Latin had been the official language for legal documentation, with some Norman French used until the beginning of the 18th century. French influence in jewellery is an important factor to the growth of the mourning jewellery industry, with skills and talents being introduced through the sharing of knowledge via a social mobility that had not been seen in the early modern age.

Cost and the essential nature of wearing a mourning jewel requires that the wearer invest some intrinsic personal affectation into the jewel and that the jewel must reflect something of its time. The 18th century essentially established the industry of mourning, due in part to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of faster methods of production and a society which was becoming more and more mobile, with greater access to education and techniques.

In 1686, the revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to Huguenot goldsmiths and jewellers emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

After this influx of Huguenot talent, the mourning industry grew along with jewellery development. Mourning rings were flourishing under a stabilised government that had not been seen under the Interregnum (Cromwell) period, as well as the new wealth that was developing from the burgeoning Industrialisation movement. Comparing this ring from the late 17th century to the daughter piece, there is a large degree of standardisation in the design elements. The daughter piece is a ring produced after the various elements of mourning in jewellery had become common enough to interpret without being seen as a jewel for aesthetic purposes. It was clearly a ring made for the purpose of grief in the style of its time. Gone are the memento mori elements (though these were still fashionable, however they had become smaller in size; see the above ring) and introduced is the name and dedication of the ring written around the band.

Language becomes the primary focus of this ring, an element that would carry through the 18th and 19th centuries. Utilisation of language to define the loving sentiment within the band of a jewel has its popular roots within posie (poesy, posy) rings.

Without the standardisation of the English language and the written reliance on Latin previous to the dictionary in 1755, rings with inscriptions of other cultures that feature similar aspects are remarkable time capsules for the late 17th/early 18th centuries. From a status perspective, this utilisation of language is accessible to a strata of society that didn’t have the luxury of formalised education, opening up sentimental jewels to new levels of society. Basic sentiments of love etched into silver and gold bands could now be given as a secret love token for a growing middle class, seen most predominantly in posie rings. In rings previous to the 16th century, more common would be the inscriptions written in French, Latin and Norman French.

Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written inside the posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content. Here, the relation of the ring to the popular literature is the key factor in understanding just how the posie’s relation to society. They were jewels that could be for the commoner, but also transient as a style of love token through society because of their simple statements.

Look towards the nature of hair and its status as a gift in jewellery from the 17th century. Prior to the rise of the hairworking industry and its prominence in mainstream jewellery, gifts of hair were considered tokens of affection and love between two people. Bury refers to The Relique (or The Relic) by poet John Donne (1572-1631) and its very early reference to a hair bracelet:

“When my grave is broke up againe

Some second ghest to entertaine,

(For graves have learn’d that woman-head

To be to more than one a Bed)

And he that digs it, spies

A bracelet of bright haire about the bone,

Will he not let us alone,

And thinke that there a loving couple lies”

Donne speaks in metaphysical terms about the unifying nature of spiritual love, as when he and his lover are dug up, they remain the symbol for holy and eternal love. From this, the poem is an excellent perspective on the sentimentality of hairwork at the turn of the 17th century. Wearing hair was an encompassing symbol of union and love between two people.

Donne wasn’t unique in his wearing of a hair bracelet, however, as Count de Grammont viewed several people wearing hairwork bracelets in the Court of the restored Charles II, circa 1660. This ties in with the rising prominence of other sentimental jewellery at that time. From love tokens, such as posy rings, to hair woven under crystal in slides, brooches, rings and other forms of jewellery, sentimental jewellery was rapidly evolving over the 17th century. Within these forms of sentimental jewellery, the use of hair became ever more prominent. Another example from 1647/8 of the popularity of hairwork within mainstream culture can be seen in Mary Varney’s letter to Sir Raplh Varney, asking to send locks of their daughter’s hair “to make bracelets? I know you could not send a more acceptable thing than every one of your sisters a bracelet”. At the time, Ralph was living in exile in France during the Protectorate. Hair tokens within families was the more common practice, but as jewels grew as a social device, so did their nature as a personal statement.

Coronet and Monogram

Use of the monogram within late 17th and 18th century jewels is more common within different classes of society which could utilise the calligraphy of a jeweller to present the details of the loved one in a jewel. When placed upon hair, the sentiment is even more important, as the message of the person is amplified through having a personal memento.

Even the simplest of designs could be attained to show the loved one’s jewel in society. As seen in the above brooch, there are many elements which connect it to the

daughter ring. Note the embellishment around the edge of the gold wire and how its’ a variation of the tighter twist of the that ring. There is an apparent difficultly in the weave of the gold wire to the daughter ring, but notice how the crown is connected to the border twist and also through the heart symbol at the bottom. It is clear that there is a focused effort to twist the design out of a single wire, rather than have separate pieces throughout the ring. For a further look into the monogram and cypher, the book Monograms & Ciphers by Albert Angus Turbayne can be viewed here.

In the use of the coronet, there is the focus upon the five strawberry leaves that are represented in the two-dimensional perspective. If accurate, this would lead to the conclusion of a duchess, yet it is of note that the coronet of a duke has eight leaves altogether. Status of the wearer in the coronet can be seen above the rim of the cornet, as this jewel below denotes with the strawberry leaves and the silver balls (eight for an earl) being on raised points from the rim:

A ducal crown would look like this in contrast:

These elements are important to note in jewellery, as the inscription of a crown relates the jewel to aristocratical echelon, while the crown in other depictions throughout the Neoclassical period, show the crown in the perspective of being a sign of honour:

Here, the crown (immortality, triumph), burning hearts (one of the strongest symbols of love / marital love), the cypress (hope), unbroken column (eternity) are traditional symbols, working together perfectly in the post c.1765 Neoclassical period to create a different interpretation. It is now an allegorical piece, allowable by those who are not of the aristocracy. This blends in well with the Neoclassical sensibilities, merging the concept of the crown with the laurel wreath.

An element that was popular for its time was the use of the laurel wreath to crown a loved individual. In the 1770s, with the imagery of the Greeks and Romans beginning to permeate society, images of classical figures with the laurel wreath as a sign of reverence, philosophy and recognition were attainable. Using this in much the same way as blue enamel (to consider a loved one royalty) was, the crowning of love was a sign of respect and honour.

However, the coronet used in context to a jewel, as the primary focus, puts its sentimental concept back on the nature of heraldic usage. Being used interwoven within the monogram in the daughter piece, it’s too specific a design to be used as a flourish or idea of considering that the loved one was royalty. Typically, this can be seen in memorial jewels and souvenirs for the monarch.

As in the design of the above slide, the crown and the monogram are used with the orbs, sceptre, skull and crossbones. Made for Mary II, December 1694, there are many similar aspects between this and the daughter ring. From the shapes, both are oval and the facets are similar. The daughter ring looses the excess of the memento mori symbolism and enhances the monogram to be the primary focus, which is simpler in intent and more immediate to construct. Without the capital or anticipation of a royal mourning jewel, regular jewels needed to adapt to popular styles of pre-designed jewels, then adapt these designs to the sentimentality. In the daughter ring, the oval shape and faceted crystal aren’t unique. Even the way the hair is roughly splayed and not finely woven into the base shows an element of haste made in its construction.

In order to show the development of the crown in memorial jewels, the selection of rings made for Admiral Lord Nelson have a remarkable display of the crown in-situ. As can be seen in the above image, this has a rectangular head in black enamel with white border, bearing a Viscount’s coronet above the initial “N” and a Ducal crown above the initial “B” over the word “Trafalgar”. The gold tapered hoop shank engraved on the outside “Palmem Qui Meruit Ferat” (Let him bear the palm of victory who has won it) and on the inside “Lost to his Country 21 Oct 1805 Aged 47″. Jewels for the monarchy have a consistency in the symbols of the monarchy, even today.

Throughout the 18th century to today, the monogram has remained popular. Its inception dates to the ancient, so it was never an early modern invention, but as a statement of personal authority and fashion, a monogram in a ring still resonates. A monogram with heraldic symbolism only enhances its message of importance for the person, a message which changed during the Neoclassical period, as the nature of the person was considered to be royalty.

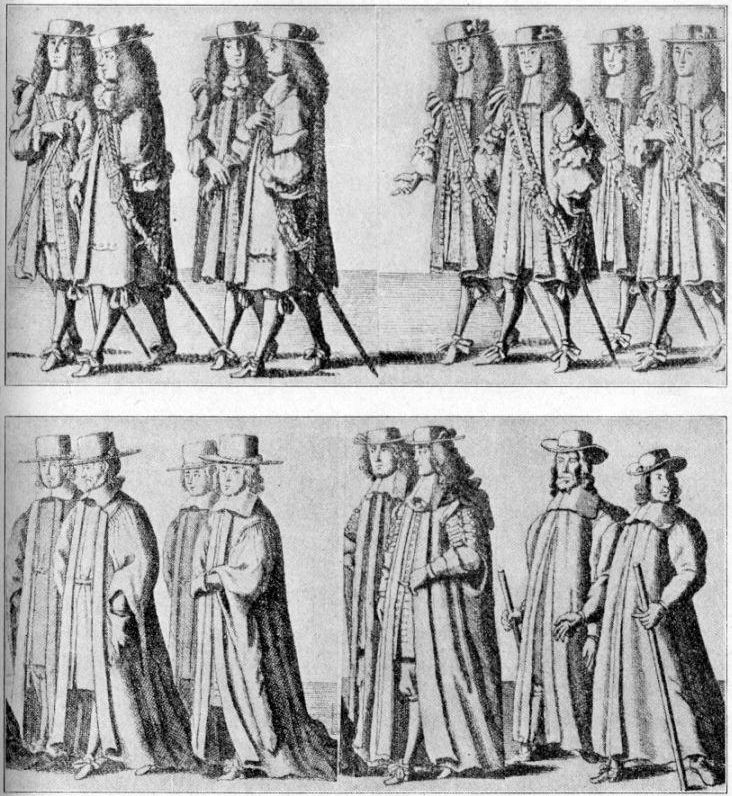

Fashion of the Late 17th & Early 18th Centuries

During the Cromwell period, the Puritan 1640s and 1650s, there was a turn against mourning dress being elaborate and decorative. George Fox, a founder of the Quakers, or Religious Society of Friends, was the son of a Leicestershire Shire weaver, was a religious radical with deep Christian beliefs. In 1682, he wrote:

‘And all your have that say, that we Bury like Dogs, because we have not Superfluous and needless things upon our Coffin and a white and black Cloth with Scutcheons (heraldic shield/coat of arms) and do not go in Black, and hang Scarfs upon our Hats and white Scarfs upon our Shoulders and give gold Rings… How dare you say that we Bury our People like Dogs, because we cannot Bury them after the vain and Pomp and Glory of the World?’ – Fox, George, Gospel – truth Demonstrated, in a collection of doctrinal books, London, 1706

It cannot be understated the importance of the influence that Puritan rule had upon a large period of English history, as well as how that was reflected throughout Europe. Much of the pomp which had surrounded the culture of mourning became important as a reflection of the family and the person in mourning. This was a representation in public, from the time of death to the funeral and beyond, which hadn’t be stabilised and turned into an industry by the mid 17th century. What the Puritan rule had done was disconnect the populace from the thought of working towards the final reward under the doctrinarian of the Church. Conflicting opinions about what happened in life after death raised the questions of what life’s meaning was about, creating the appearance of jewels and fashion to be contextual for the mourner. Until the reestablishment of the monarchy, a stronger push by the Court to formalise mourning costume and the standards surrounding it led to much of the standardisation in presentable mourning symbolism that is still recognisable today.

For this ring, its important to factor these changes in. The use of the monogram to relate to the identity of the girl who had died strips away any thinking of mortality, to just isolate the individual and the aristocratical status within the coronet.

One common element throughout the mourning fashion of Europe was that there were to be no reflective surfaces for all genders. As standardisation throughout the second half of the 17th century affected Europe, fashion began to be costly and also necessary for families to represent themselves in mourning.

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), whose diaries show a great insight into culture at the time, have a great insight into several funerals throughout his lifetime and the impact fashion and cost had in his life. Pepy’s Aunt Fenner died on August 1661 and Pepy’s father carried out funeral arrangements. As his father was a tailor, the family could not afford to purchase mourning for relatives, but instead tailored it themselves. The sentiment he wrote was ‘all in mourning, doing him the greatest honour, the world believing that he did give us it.’ Another aunt died one month later, with Pepys and his wife wearing the same garments, making him write: ’To church, my wife with me, whose mooring is now grown so old that I am ashamed to go to church with her.’

Much of the cost surrounding mourning was in the cost of new mourning costume throughout the three stages of mourning. For the poorer classes trying to emulate these styles, the burden of household and General Court mourning was a necessity, with anything less being considered without dignity. Furthermore, the influence of styles and the industries of silk, which many of these garments were created with, promoted high cost. To investigate this and look to how the French influence on this ring was important, a view of the turn of the 18th century France is important, along with is impact towards Britain.

France, at the turn of the 18th century was ruled by Louis XIV, also known as the “Sun King”, who had ruled for 67 years. His full reign of 72 years and 110 days is the longest of any European monarch in history.

Louis had a tremendous influence over art during his reign, introducing a militaristic influence over his depiction and presenting dominance in his rule throughout France. From the installation of triumphal arches, to the indoctrination of medals, Louis was influential in popularising his right to rule amongst the population of France.

Industry was growing at a rate where the demand for fashion was defined by the fabric, rather than the cut. Silk collections in France were introduced biannually in Lyon and copied by silk designers across Europe; causing women in high-wealth to only be able to afford seasonal changes in their dress. The high cost of silk led to a silk dress ranging from £10 to £60, which is remarkable when considering an entire house could be purchased for £500. In mourning wear, the silk industries had proprietary of what mourning fashion would be. While many women re-trimmed their dresses, French and English silk industries lobbied their Parliaments declaring that many months of Court mourning were leading to declining sales. By 1716, France had cut mourning by half, with another declaration in 1730 by even more.

What the rise in industry shows is that the accumulation of wealth amongst a growing society was demanding the need of new fashion. A society driven by the wealthy invest money into an industry and create new wealth amongst those who control those industries. Look to the following image of Lousie, Duchess of Bourbon, eldest daughter of Madame de Montespan and Louis XIV in mourning for Louis III de Condé:

Louise’s dress is trimmed with fur ‘robings’ and matching cuffs – the ‘robings’ here would likely by miniver. The train is lined with fur and her black belt is overlaying her skirt, in her hand she holds a handkerchief. In all, the opulence of the dress and its relation to many different materials and elements are reflective of the industries that were driving production at the time.

A society dominated by art and industry, which leads to a France of artistic influence in its jewels of love and sentimentality.

Value

Life in the 17th and 18th centuries was important. The great shift of thought which challenged religious beliefs and the very nature of what life was for promoted the values of love and relationships. This is reflected within the fashion, the design and the very sentiment of the jewellery and art that was produced when this ring was made. For the precious memory of a little girl, this ring transcends aristocracy and becomes a simple and striking token of how a lady would have been grieved. Its grandeur comes from not being over-designed and heavily opulent, but in the simplistic manner that the hair is placed under the faceted crystal, the loosely designed cypher and the excessive sentiment underneath the bezel and under the band. When a ring has so many things to say in such a small item, it speak to the grief of the family and the love that resonated within.