A Collection & The Late 19th Century

Mourning jewellery holds a certain fascination in jewellery collecting, far more than any other modern style of jewel. They are relics, not only of their time and culture, but of the people who wore them and the people who they are dedicated for. Collecting mourning jewellery is to one as collecting a life. Their mystery, based in the smallest of dedications, be it written, hair or photograph, are all trinkets of a time that sparks the imagination as to who they were created for. As collectors, we are constantly trying to reclaim and relive some part of time that is lost to us. This makes us more invested in discovering new elements of a certain period that enlighten us and make us feel better connected to the past.

Mourning jewellery collecting isn’t about the transactional aspect of collection, the money invested in the weight of gold or the perfection of a diamond isn’t worth the same amount as the twist of hair placed in the back of a pinchbeck brooch. Having something so intimate from someone is quite an honour for the mourning and sentimental collector; it’s a perfect connection to the individual. This is not a uniquely modern sentiment, but one that is innate and prehistoric. Much of the negative perception of collecting an element, such as hair, is from the 20th century. How could anything so personal that is given be considered negative? Indeed, even locks of hair from the famous garner a great deal of excitement, as even cuts of Napoleon’s hair sell for great deals of money. One such lock sold for £8,731 in 2010 in New Zealand. Collecting isn’t simply for the wealthy sociality or the aristocracy, but for everyone. Mourning and sentimental jewels are humble in their cost and those who appreciate the allure of a photograph over the cut of a gem are certain to amass a collection quickly.

Recently, a number of jewels were bequeathed to me by a collector that have a distinct focus on the second half of the 19th century. In the same way that I would approach a mourning jewel of a specific time, let’s look through the collection and discover insights into the 19th century, hairwork, accessories and photography.

The Changing Landscape of 19th Century Jewellery

Three of the jewels in this collection contain photographs, each from the last years of the 19th century.

As quickly as the technology spread, jewellery and fashion were fast to adopt photography. The wearing of a photograph became linked to mainstream fashion; its use as a signifier of social status as well as a personal device of memorialising a loved was a revolution in the concept of memorial / sentimental jewellery. Worn on the outside or in, closed or open, photography and jewellery began a relationship that still continues to this day.

Replacing the miniature as a cost effective means of holding on to the memory of a loved one, lockets and pendants adapted to accommodate photography quickly. Following on from the 1830s, jewellery was becoming smaller and more adaptable for modern fashion, lockets and pendants weren’t as obvious in costume as they had previously been. By the 1840s to 60s, small lockets were accommodating photography and adapting styles as fashion permitted. Wearing the picture of a loved one over the heart was one of the most powerful symbols of affection between people; it was a secretive function and transcended any particular fashionable style.

In brooches, photographs began replace hair mementos, or often have hair on one side with a swivel to a photograph on the reverse (1850s and 60s). Even rings were not exempt from photographs, with signet rings opening to an image underneath, and eventually mourning pieces of the 1930s and 40s would be of Bakelite with photographs placed on the top.

The dry plate photographic process, invented by Dr Richard L. Maddox in 1871, revolutionised smaller, cheaper photographs, allowing them to be used in jewels. Amateur photographs grew in popularity when Eastman Kodak released the handheld camera, with the marketing slogan of “you press the button, we do the rest”. Now, it was not necessary for a formal sitting and a photograph that could be placed inside the jewel. By the 1880s, the ubiquitous nature of the photograph was starting to replace traditional items of sentimentality, notably hairwork was declining in use as well as miniature portraits had almost become obsolete for common use by the 1860s.

Notice in these jewels the simplicity of the photograph itself. In the brooch, the gentleman is captured in a formal sitting, with turned down collar, no tie, waistcoat and jacket. The photograph is cut and placed inside a pre-designed, Pinchbeck brooch. These alloy brooches could be bought in the same manner that a regular locket for a photograph would be today. The photograph was of a typical size and simply cut to fit. On top of the photograph is a very simple cut of hair, twisted with strong. What is striking about the brooch is the immediacy of the subject. Presumably given as a love token, this brooch is very humble, yet free from any doctoring by the person who gave it. Love tokens don’t require the highest of materials to convey their love, but simply the hands of the person who is giving it to their loved one.

In the fob chain, the excellent weave of the blonde hair is joined by the fitting of pinchbeck that has the initial ‘I’, embedded with garnets and a pearl, which is typical for the 1870-1900 period. The photograph here looks to be even more casual, taken, then cut with the offset of the subject. It also looks to be a 20th century addition, as seen in the collar, tie and hat, yet with the hairwork, it would appear to be a family’s choice. Re-appropriating hairwork outside of the family unit is much more unusual than a locket without any other form of dedication; one must have a physical connection to the person in order to wear it.

As written about in this article, Charms, Chains and Bracelets, charms on a fob chain are personal and not something that one would pre-design. Much like a charm bracelet, they are tokens of day to day life, a collection of places and elements that one might assist in getting through the day. This fob chain’s photograph fits into that paradigm of personal, it doesn’t have any element of being staged and fits the honestly of the chain.

Of the more unusual amongst this collection is the fob chain with the two hair colours, blonde and brown. Featuring two different weaves for each, the hair would be colour matched to approximate the hair colour of the people who it was dedicated towards.

Accessories, Mourning, Sentimentality and Daily Life

Brooches gained in popularity during the 19th century, becoming the fashionable token of affection and gift giving for jewellery. This balanced with the changing fashion, rebounding from the voluminous crinoline of the 1850s to the more slender bustle and hooped skirts with high collars and then boned bodices. Style had changed enough that the smaller brooch, worn at the neck, became a hallmark of Victorian style. A house in mourning or a woman’s fashion could clearly be stated by the token of affection worn to prominently.

By the 1880s, mourning was in decline. Victoria had been in perpetual mourning since 1861, leaving an extended period for popular fashion to remain static. Consider modern fashion being dictated by popular figures and how often changing styles influence lifestyle. Previous reigns had always been the epitome of style and fashion. The ability to travel, spend money on a lavish lifestyle and art was typical of a monarch or members of the aristocracy. If royalty visited, popular fashion would adapt the strange fashions that they would introduce and it was popularised in fashion plates and books. Victoria’s engagement with mourning, along with all the other sentimental rituals introduced in the 1840s, helped to affirm a British cultural identity, one that could be replicated across the colonies. This, however, was not conducive to a younger and growing middle class, one that could access cheaper and more elaborate jewels.

In 1885, the Princess of Wales was approached to see if there could be a relaxation of the mourning code. A response was only given two years later, during Queen Victoria’s State Jubilee, that the Queen agreed to wear silver jewellery on state occasions. This led to a surge in silver sentimental jewllery, a surge that would effectively end mourning as a popular fashionable form of jewellery and relegate it back to its functional roots. It would take another twenty years to end the industry of mourning fashion, which was not revived following the mass attrition of World War I.

Hair, as a material for mourning and sentimentality, was becoming unfashionable in the public eye, also. Even the interest in jet was on the decline, with less than four hundred workers left in the industry.

As the jewllery industry needed to thrive in a market of change, the focus of fashion fell upon silver. Queen Victoria’s relaxation of mourning code allowed for women in fashion to wear silver, even during periods of mourning. Considering that the mortality rate was high and mourning code enforced women to wear mourning, even for deaths outside of the immediate family, the imposition was difficult. Being the centre of the family and the household, the mother and wife in a family unit was to represent the family at all times. When a new fashion could break this, then existing industries needed to adapt to change.

In 1887, the Birmingham Jewellers’ and Silversmiths’ Association was founded by local companies, based around the poor state of business, problems in the jewellery trade, design training and crime. By 1893, they had 186 members, showing the rapid growth of the silver industry. In 1890, the Comstock Lode discovery of silver in Nevada, USA increased the world’s supply and the price fell rapidly. This coincided with duty that had applied to 18 carat and 22 carat gold and to all silver were abolished, paving the way for lower classes to purchase sentimental jewels, known as the ‘trinket trade’. Silver sheet was cut and stamped with the appropriate sentimental design, if there were more than one piece, then they were soldered together. Mass production of silver jewellery in brooches, charms and trinkets escalated exponentially.

With such a high rate of production, ubiquitous designs only strengthened the symbolism previously used in mourning and sentimental jewels. The Victorians are known for the proliferation of symbolism in flora and fauna, which their presence in jewellery only helped to popularise. The adaptation of the floral style was one that resonated with the language of flora and fauna. The Illustrated Language of Flowers by Anna Christian Burke categorised over seven hundred elements of flora and fauna, which gave the Victorians a resonance of design elements to represent their emotions in jewellery and ephemera designs for gifts towards others. Even more symbols were built upon this, increased only by the discovery of challenging thought in a time where science and religion were becoming equals, to make the smallest element of design important to represent a relationship in society.

In the silver black enamel dove brooch, where the bird in inlayed with seed pearls and carrying the olive branch, its sombre sentiment is one that followed the classical motifs that remained popular in the 19th century. It has undertones of religion and peace, which made it very safe for the late 19th century environment, in terms of classical imagery. The reverse reveals another photograph, this one crudely cut to size, indicating that it was a personal addition to a pre-designed brooch.

During the mid 19th century, Pinchbeck was the popular way to emulate gold, stimulated by the Hallmarking Act of 1854 that allowed the use of lower grade alloys in jewellery. Pinchbeck and other alloys are common in jewels which identified with the look of what mourning was trying to achieve. Cheaper jewellery that looked large, with the elaborate black enamel, could be worn in costumes that were becoming larger and more voluminous. With the changing fashion, silver took over from this and relinquished the need to emulate gold, while offering more tailoring of designs. Brooches with names, ‘mizpah’, birds, roses, the horseshoe, the hand, buckle/garter, harps, hearts, crescent and a nearly endless variety of silver trinkets could be stamped and worn.

Even Her Watch Was In Mourning

A watch which more testimony to the depth of her grief dangled on the bosom of a conspicuously widowed woman in a Broadway store yesterday morning. It was one of the round crystal nuggets popular nowadays, but the face was of black enamel, the tiny hands and the Roman figures in silver, and it was fastened by a black enamel and silver pin shaped like a pansy, doubtless because pansies are “for thoughts.” – Even Her Watch Was In Mourning. (1894, February 15). Southern Argus (Port Elliot, SA : 1866 – 1954), p. 4. Retrieved November 9, 2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article96937958

Just as the perception may be that mourning jewellery and fashion was eradicated from general lifestyle, this article from 1894 articulates just how the identification of mourning was still embedded within the popular mindset. People who had been locked into mourning for grief aren’t immediately going to put aside the widow’s weeds due to a changing fashion. The younger generation embraced the new change more than the older generation, who carried forward the social propriety of death in fashion.

From 1900, there was a significant split in jewellery styles. Court-worn jewels were still based around the Rococo Revival style and using highly privileged, material-based gems, such as diamonds. This was normal around European Courts and remained consistent from the 19th century. In Europe, the organic influence of Art Nouveau and its use of coloured gems and enamel became popular. The Arts and Crafts movement flourished in Britain as a response to mechanisation; bringing back a return to traditional crafts. This remained consistent up to the beginning of the First World War.

South African diamonds produced 90% of the world’s diamonds in 1890, with a slight interruption by the Boer War in 1899-1902. White gold and platinum were used to enhance the look of the diamond, leading this to become one of the most popular styles in fashion for the time. Its influence can be seen today, with ‘white’ jewellery being more popular than the silver influence of the 1880s simply because diamonds were enhanced by the white colouring of the metal and diamonds themselves were cheaper and more accessible.

‘Garland’ style jewellery was made popular by Cartier, which referenced Louis XVI style, featuring garlands of laurel leaves, lace patterns, ribbon bows and tassels. This style resonated throughout Europe and America, but only in high wealth. Art Deco had its origins in this style, with Boucheron, Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels all experimenting this style, but adding gems and exploring its development.

It was the financiers who made this development possible. At a time when new wealth could define new styles, going beyond the previously established family-based old money, Americans began to spend their money in Paris, leading to the rise in jewellery production houses and their proliferation. Tiffany & Co. developed by this money and presented their quality work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. Notably, their contribution to jewellery development was the Tiffany Setting in 1886; a diamond setting above a ring which lets in as much light as possible to the stone. René Lalique, whose influence to Art Nouveau is exponential, was awarded a Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition, leading to the popularity of delicate, organic styles in jewellery design and development. Methods, such as the Plique-à-jour enamel work (meaning ‘letting in the light’), were fundamental in how jewellery design was reacting to the previously consistent styles that had represented the late 19th century.

Pins and Accessories

“It is curious to trace how little by little our most ordinary conveniences, such as needles and pins, thimbles and crochet-hooks, came into use and were adapted to the daily needs of feminine work and fripperies. The first needles were probably made of fishbones, carefully sharpened and pierced, and even before they were invented women pierced holes in the skins and fabrics they manipulated with little bone skewers, and passed fine threads of sinew through the hole thus made… There were a great many needle makers in Paris in the thirteenth century, but when Louis Quatorze was King they had all disappeared. Needles were then made entirely hand, and were consequently expensive, but by some means the needle manufacturers got translated to England, and to this day there is no present more valued by notable Frenchwomen than a sock of the best English needles, not simply bought as such, but selected here by some one who knows what needles ought to be. The small case or casket in which ladies kept their precious needles was frequently made of gold, and even set with jewels and very often attached to the chatelaine which even dames of high degree wore at their waists.

Paris pins had a great reputation in Molière’s time, about 1656, but the pinmakers disappeared before the end of that century. England had even then become the home of the industry, but a few were still made at Laigle and Rugles, in Normandy, though the only way of making them go down with French ladies was by selling them in English wrappers. There were then as many varieties as we have now, including black pins for mourning. – NEEDLES AND PINS. (1897, August 28). Adelaide Observer (SA : 1843 – 1904), p. 32. Retrieved November 9, 2015, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article162380172

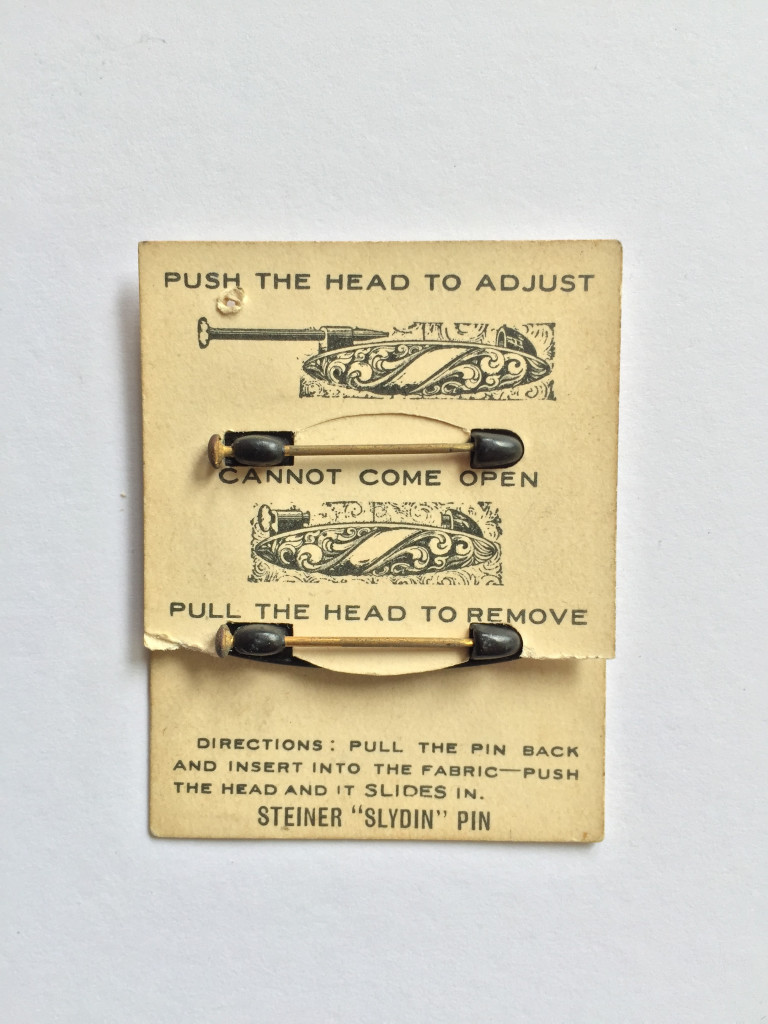

What is charming about this article from 1897 is the national pride invested in the quality of English pins. Pins were a necessary piece of daily costume, being used to fasten a dress, hat or accessory. It is of great credit to the mourning industry that it could appropriate even the smallest element of daily life and turn it into something that was required for daily grief. Such an innocuous accessory wasn’t overlooked, as can be seen in the buttons, charms and smaller elements of this collection.

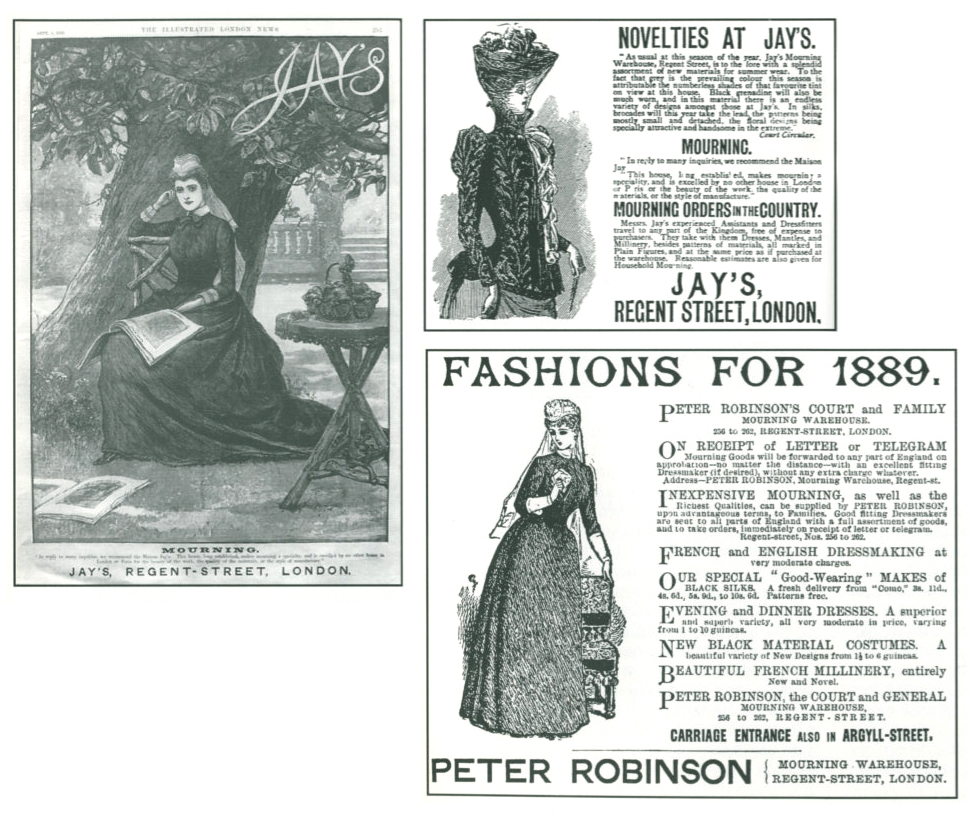

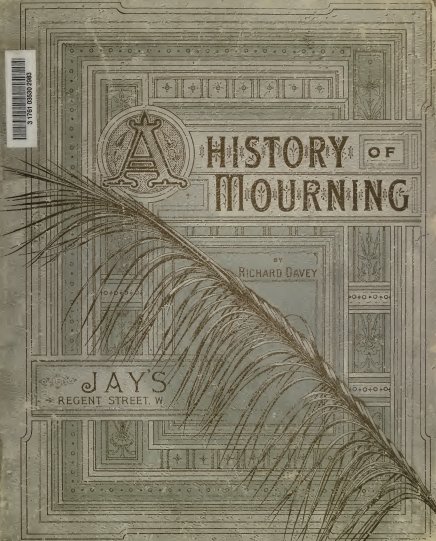

Businesses like Jay’s Mourning Warehouse, of 12 Regent St, thrived on this level of detail, earning enough capital to remain open from 1841. Beginning as a ‘shawl warehouse’, their popularity from Victoria’s mourning in 1861, so much so that Jay’s commissioned a book written by Richard Davey, ‘A History of Mourning’, which also looked favourably on their contribution to mourning. By the 1850s, their scale began to grow, buying up next door businesses and annexing much of the block.

Much in the same way that the silver industry thrived after 1890, the mourning industry thrived on the smaller tokens of affection. Whatever was cheaper to produce could only make the proliferation of the concept easier. Jet and its imitations are the same, being a popular material, but easy to approximate with other materials. When a design could be stamped or moulded, vendors could sell at a high rate. For jewels like the ones in this collection, the smaller elements of design in the pressed alloy of the pinchbeck allows for easier populate in popular fashion.

Even the detail in the vulcanite buttons reflects the care and detail of Victorian design. The daisy and acorns are on display, surrounded by the acanthus, all in a functional item that would be worn on daily basis, which can be seen in the wear to the reverse of the pieces.

In Memory Of

What collections of jewellery tell the viewer is more about the person who collected them. Why did they collect these jewels? Was it for the sentimentality? The story they can tell? The craft and design? In this very specific collection, the slant towards the latter 19th century opens up a larger narrative about jewellery history, the society of the time and the fascination with love and sentimentality in modern fashion. From the smallest Victorian accessory, an entire universe of knowledge about the changing industry and the craft of the design provides an insight into daily life.

This collection will remain together, a group of jewels that work as one, to carry forward the stories of the 19th century for future generations to learn about daily life.

Further Reading

The Art of Hairwork Collection

Culture, Conflict & Mourning in the 17th & 18th Centuries

Mourning Fashion & Jewels During George I & II

Mourning Fashion & Jewels During George III

Mourning Fashion & Jewels During George IV