Alas! She’s Gone, Part 2

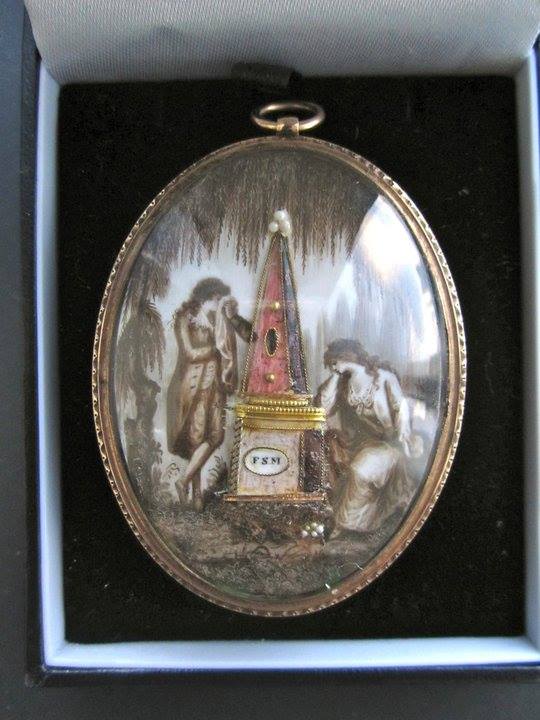

In a connection between a parent and child, the basis of the family is measured by their love and their faith. In this Neoclassical jewel, all this is represented, from the very positioning of the family, to the literal depiction of the heavens above. In this second part of the analysis of the jewel, let’s look at these elements and what they represented in the late 18th century.

For part one of this article, please visit:

Children

Remarkably, this jewel has two children next to the gesturing father, both informally in poses of grief. A smaller child in a black dress is at her knees in front of the tomb, while another in a white dress stands leaning against it. It is almost as if the father is presenting the scenario with his gesture, inferring the impact of the passing has a greater impact upon the children.

A child in mourning is the ultimate symbol of family grief. The child is what carries forward a memory and validates the parent’s existence, so it is with great grief that the loss of a child could be worn as a jewel or in fashion. In the reverse of this, a child in mourning for a parent or relative brings the individual back to the reality of what death was. In modern society, death is desensitised and removed from immediate reality, while in the pre mid-20th century, children were very much involved in death and mourning ritual. The development of fashion around death begins with the child and the realisation that time is fleeting, so let’s discover how children’s costume developed in fashion and how parents produced jewels to deal with the loss of a child.

Children were part of the mourning ritual in the same manner as adults. From the perspective of costume, children were required to follow the stages of mourning and wear the appropriate garments and also attend funerals. For twelve months, children were required to mourn a parent, with the first six months in dull black or crepe to show deepest mourning. For the following three months of this period, the Ordinary mourning phase meant that they could wear black silk without crepe. For the final three months, children were allowed to wear half mourning colours. In General Court mourning periods, children wore mourning according to the mandated requirements, as well as for all relatives.

The black dress of the one girl and the white dress of the other denote grief in both conventional styles of the late 18th century. The proximity of children to mortality previous to the mid 20th century was far closer to the fact. Death was a part of life, rather than being disconnected through funeral practitioners who handle the body after death. Funerals began with the home, often with the body lying in state, forcing children to deal with the reality of death and practice the art of mourning.

Heaven

Depictions of heaven in Neoclassical jewels follow certain idyllic standard that would generally develop throughout the c.1760-1820 period. Its symbolism is an obvious one and it is not an element to discredit, even during the humanist movement. The heavens are important as that’s where the soul will ideally eventuate and this is transcendent of religion, which is why it compliments both Catholic and Protestant values. In the following jewels, note how the use of the angelic presence is rendered in the design and the placement in the heavens. In the jewel of this article, the message of the jewel is ‘GLORY’, a message of positive judgement in the afterlife.

Ecclesiastical symbols are important for mourning jewels, as the faith of the wearer reflects back to where they feel that their loved one has gone. Of course, this final destination is required to be peaceful and idyllic, free from the negativity of our physical reality and whatever judgement that comes from this will be a positive one. This is why in these jewels, the soft clouds, winged cherubs, with their childlike curled hair, remain standard. What is interesting are the messages that are carried by the cherubs. In this French piece, the message is ‘L’AMITIE’, bringing the concept of the relationship of the deceased and the lady in mourning being one of friendship. It is a message from the piece, which clearly states to the viewer that its sentiment isn’t family, but loved enough to be guaranteed a place in the heavens.

‘TO BLISS’ is one of the more common statements in a mourning jewels , as can be seen in this jewel and the one below. The sentiment is a passive one, benign and beautiful to offer the passing soul into a better place. It is largely non-denominational, being pre-designed into the jewel by the miniaturist and requiring little tailoring when the piece would have been commissioned.

In this jewel, there is the combined statement of ‘TO BLISS’ and ’SACRED TO THE BEST OF FRIENDS’, linking together the above two sentiments of jewels. One being about friendship, while this promotes the peace of the soul in the heavens. The exceptional detail of this miniature brings into detail the cherub and the muted, sepia shades of the clouds, bringing an exceptional level of detail into the Neoclassical heaven.

Quite interesting is how the angel is more fully formed in this mourning miniature, but it shows a clear difference between the soul of the child that is breaking free from the tomb and being welcomed into the arms of the heavens. The level of quality here is truly the height of the Neoclassical movement and brings together all the primary symbols in a mature and highly detailed way.

Representation of heaven in Neoclassical mourning jewels aren’t as common as the urn or willow combination. It is a special statement of faith for a loved one

Fathers in Mourning

Parents in mourning for their children often display many of the elements that provoke the sadness that press deeply upon the viewer. When a male was seen in the mourning scenario, there’s a higher degree of personal identity applied to it, as the male wasn’t the allegorical representation of perfection or the self. This belonged to the female, who was generally a conceptual figure of the ideal. In these following jewels, the family and the father are important artefacts of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

In this jewel, the father is also surrounded by his children, making it a personal insight into how the family unit was constructed and considered to be displayed in society. There is special attention paid to the father in this jewel, as he sits, cross-legged, with his head buried into a handkerchief, prostrate at the urn of his departed loved one. He is dressed in contemporary fashion, wearing a white cravat and pantaloons, with a dark coat, waistcoat and breeches, which correlate to mourning fashion in men during the late 18th century. This matches the cut of daily clothes, as gentleman did not need to go to the extremes of women outside of court. In all, this is a very personal sentiment and the gentleman was clearly in a good level of society for the mid 1790s to be able to depict himself in such a fashion on a piece. This speaks to the wealth of the miniature and how it would have been painted after the death of the person they are grieving for. It is as much as a piece designed in a sitting, as to one that was made spontaneously.

More naive than the others, this ring still holds a personal element of the male in mourning. No other figures surround the young gentleman, but his placement is almost identical to how a lady would have been portrayed in the same instance. The urn is much larger than he is, forcing him to become secondary to the remains of his loved one, but this doesn’t take away from how close this would have been to the gentleman.

In this French mourning miniature, what can be assumed to be the parents of a lost child are both in the same poses as one would expect from a lady, or ladies, in this scenario. The gentleman covers his face with a handkerchief, while the lady leans against the tomb. It is interesting to see how sepia miniatures were re-designed from a specific model and made more personal to the wearer. From contemporary fashion to the body language, this is a moment of its own time. Items of higher quality in their painting tend to be those that can capture more detail in their design, while those of a simpler quality would have had elements that a miniaturist would redesign much more primitive, such as messaging and dedications.

This gentleman stands next to the coffin, placed on a bier and defies many of the symbols that were typical of Neoclassical symbolism. It is an incredibly personal depiction, one that leans more towards a direct portrait, but captured with the style of contemporary sepia paintings. The casual nature of the gentleman is as he would have been in life. Held in a stickpin, it is also a fashionable male jewel for daily wearing.

Alas! She’s Gone

All of the elements that construct a jewel aren’t so simple as they may seem. From the moment that a person decides to commemorate and honour another with a certain object, the emotional value is instilled within it. With this jewel, those elements come to the surface and offer a window into the lives of people who felt personal grief, their beliefs and how society represented this for the time.

The afterlife and its mystery maintains an element of fear, as it cannot be defined. The turmoil that society had gone through during the early modern period had defined the society that exists today, questioning what we do not understand. In art, these representations never lost a sense of piety to the soul of the loved one and where their afterlife may be. In this case, the heavens offer the sanctity of a peaceful eternity and the grieving family will join that soul there in the future.