Alas! She’s Gone, Part 1

Personal elements of mourning are individual and unique. There’s no prescribed way of behaving when one is in grief, but the way it manifests in fashion and art are the unique ways that a person can display their grief. In the post c.1760 period, the Neoclassical movement allowed for a unique outlook on how death could be represented. Prior to this period, death was ecclesiastical in its design, with the elements of mortality representing final judgement under God. Christian faith had been challenged since the 15th century in mainstream thought, with the Great Schism and the subsequent Protestant Reformation breaking the Church and personal beliefs in faith apart. When this is enabled or supported by a monarch, in the case of England, Henry VIII, a look back at the personal values of faith and the afterlife are questioned.

In this exquisite Neoclassical jewel, we can see how these values are represented. There are elements of faith and personal identity on display, which all conform to how mortality was viewed in the latter 18th century.

Jewels of the late 18th century were standardised, but arguably explored the most diverse designs in jewellery design of the modern period. This Greco-Roman revival period began when excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum provided classical discoveries in 1711, then resumed with major excavations in 1738, igniting the passion and interest in artists, thinkers and antiquarians. What stemmed from this was a change in how relationships were represented in jewellery. A major humanist movement in the Enlightenment was represented in Neoclassical jewels, which represented allegorical scenarios in concepts of life and society. As such, jewellery depictions of classical figures represented the modern self for the c.1760-c.1820 period.

What this jewel does is challenge the classical symbolism with the elements of the personal. Classical allegories were important to represent the ‘self’ in these jewels, but here, we have the full family on display. It can be assumed that the mother is the one who has departed and the two children mourn next to her tomb, with the father gesturing towards it. In the heavens, the angelic figure beckons the soul to the heavens in order to find glory. Flanking the left of the piece is the willow and a row of cypress trees grow into the horizon. Remarkably, this is captured in perfect detail, having a depth of perspective and gentle shading to mark out the light, as well as the rise and fall of the hill. The cypress trees point to the heavens, as is their symbolism and the willow denotes sadness through ‘weeping’.

Jewels of this age are contextually difficult to view, outside of the obvious symbolism. It is easy to say what the jewel is, but there are so many other elements that make a Neoclassical mourning jewel. Just as today, the symbols of mourning are popular among certain circles. Mourning became ‘fashionable’ through mainstream media. There was a high level of growing affluence in middle classes and mourning fashion was adapted in jewels and art. It relates back to classical symbolism as well as literature, as shall be revealed later in the article. The romanticism associated with being in mourning is relatable and poetic, hence why many jewels are often misallocated with being actual jewels for mourning and not just fashionable wearable items. What we need to identify with this jewel is that it is clearly and profoundly a jewel created for the death of a lady and the family is in profound grief. This is closer to a miniature portrait of a family in mourning, rather than the classical jewel that it could easily be attributed to. Certainly, it is romantic and classical in its depiction, but every element from the fashion to the sentiment is there. Let’s look at some of these elements that construct the jewel.

Cypress

In the use of the cypress, this jewel associates itself with many of the Neoclassical style of jewels that were contemporary for mourning. Viewing a cypress tree isn’t as primary as that of a willow, but it has a connotation that contemplates the afterlife.

Known as the ‘mournful tree’ by the Greeks and the Romans, the tree was sacred to the Fates and Furies as well as the rulers of the underworld. The tree would be planted by a grave, in front of the house or vestibule as a warning against outsiders entering a place corrupted by a dead body. Romans would carry branches of cypress as a sign of respect and bodies of the respected were placed upon cypress branches previous to interment. It is such for reasons as this that the tree still survives in the Muslim world and in Western culture, the cypress designates hope, as the tree points to the heavens. Here, there is a great continuity of usage for the tree, as despite its cultural interchange, it still remains understood for the same purposes in death.

It is the usage for its heavenly motif that we focus on for jewellery in the Neoclassical era, as the period of around 1760 is when the symbol came into regular mourning depictions, painted on ivory or vellum. The cypress is mostly shown in the background to the willow in the foreground of a mourning depiction, as the mourning woman would often interact with an urn, tomb or willow, but rarely with the cypress itself. Due to is constant usage in cemeteries and reflecting the classical usage of planting a cypress upon death, the cypress is still most commonly seen at the graveyard and the mourning depictions of the tomb or urn on plinth are reflective of that. The cypress’ seen flank the cemetery as they would in reality. Other depictions of the cypress may be the lonely cypress on a rocky outcrop or a singular cypress surrounded by other mourning symbols.

By the 19th century, the cypress was depicted in leaves and branches on jewellery, rather than the full sized depiction. In this way, it could be utilised with other symbols as the Neoclassical concept of depicting full mourning scenes had given way to more specialised and smaller depictions of individual symbols to convey a meaning.

Willow

The weeping willow is heavily symbolic of grief, sorrow and mourning, even physically, it stands as an analogy to human grief, with its back bent over the subject, be it a weeping figure, a tomb, plinth or any other mourning subject. Flanking the left side of a mourning jewel in the Neoclassical period was typical for this element of symbolism. From an artistic perspective, it was important in that its leafs could be painted in a border that would frame the image, rather than being a background element in the Neoclassical depiction. This low hanging element, related to sadness, made it the perfect encapsulation of mourning for its time.

The development of the willow in its design went from the element of the tree to the physical viewing of the branches and the trunk. Much of this has to do with the structure of the Neoclassical shapes that encompassed the jewels, themselves. Painted on ivory or vellum, the allegorical situations that were painted needed to be adapted for their design. The high, north to south navette style grew from the oval styles of the 1770s and gave the painter a larger canvass to work with.

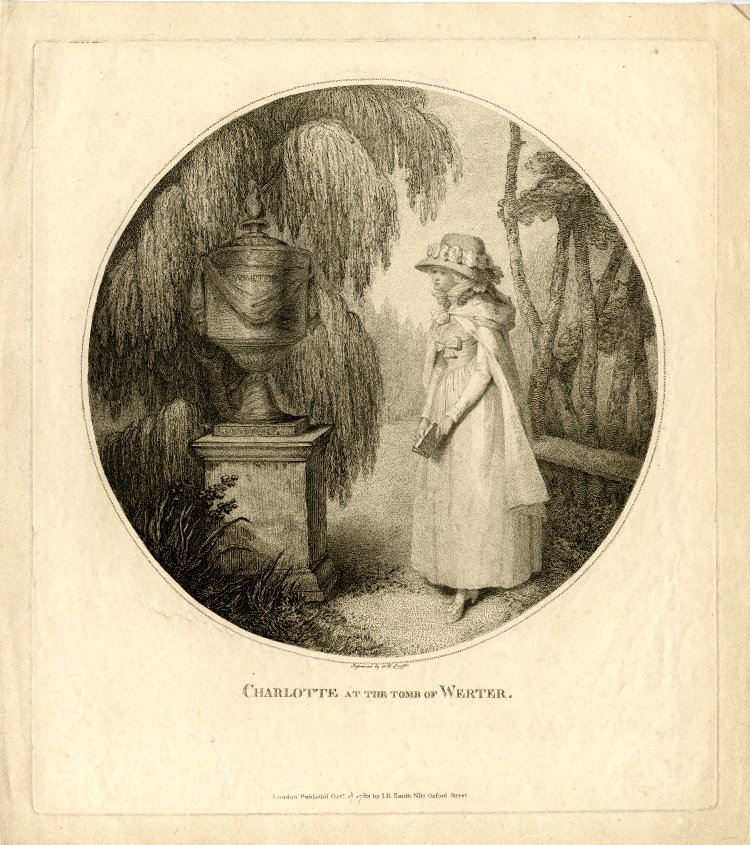

Popular culture grew the elements of mourning symbolism, so much so that Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, published in 1774 and revised in 1787, was important to the Romantic movement, so much so that even Napoleon Bonaparte carried a copy with him during the Egyptian campaign and wrote a soliloquy in the style of Goethe. Its story involves the titular protagonist committing suicide over unrequited love and being buried under a linden tree. The popularity of this book generated much popular fiction and instilled the symbolism of the weeping female character next to the tomb and the willow, as seen by the following ‘Charlotte at the Tomb of Werter’, 1783:

Popular culture is the most effective way of creating identity within symbolism. If there is a cultural movement or predilection of style that is used in a way that can create an icon, such as the willow here, then it will become a symbol that crosses cultures. Considering that Napoleon himself was a fan of the work and Napoleon defined the classical style through jewellery, then popular culture can drive the message of mourning beyond a religious or monarchial figurehead.

In this ring from 1785, the willow is displayed in its full depiction. As a standard of the sepia jewels that were created at the time, this is a pristine example of the symbolism that was popular in mourning jewels during the 1780s.

Deep brown hues and reds to symbolise the earth and the blood are utilised for symbolic effect. Hair was often chopped and mixed into the paint for even greater sentimentality; the person who was being remembered for whatever capacity became the jewel itself.

This is where it’s important to factor in the ideals of what the Neoclassical movement was. This was a time when the classical Greek and Roman sculptures, art and views on philosophy had a rebirth in a time that was primarily dominated by ecclesiastical means. There needed to be a way to show this art and present it upon the person, rather than simply a work of art in a house, the person became the figure to display the art. This relates back to the nature of the person and their role in sentimentality and mourning. The person was not something to be judged at death with a firm control of living inside the paradigms of piety to have this final reward, but the person, and the family, were the targets for grief, mourning and essentially love. Being able to display this affection through the use of Neoclassical philosophy was a major turning point for Western cultures.

Sepia was ideal for this, it involved all the principals for love and it upheld the affectation of the late 18th century perfectly.

Age wasn’t a factor in the usage of the symbolism, either. To be so firmly entrench in the mainstream mindset, this ring shows that no matter what the age of the person who was being mourned was, they still upheld modern fashion. “Prepare to Follow”, a sentiment of notice for those to be aware of their mortality, is used for William Wilton, who died at age 51 in 1785 (which, for a mortality rate of around 40, is quite a decent year). More importantly, William would have been reaching his maturity during the height of the Rococo period and none of those motifs are reflected in the ring.

Tomb

Male and family mourning jewels are often more immediate to the subject of the mourner in the 18th century. This isn’t to say that the depictions of the male/family in-situ are a literal display of the gentleman and children in the scenario, but that they are more defined because of their time. In the use of the tomb, the tomb is still allegorical, as are plinths, when shown in a jewel like this.

Using the tomb in a Neoclassical setting was popularised, just as the urn/willow combination were, as seen in the Tomb of Werter.

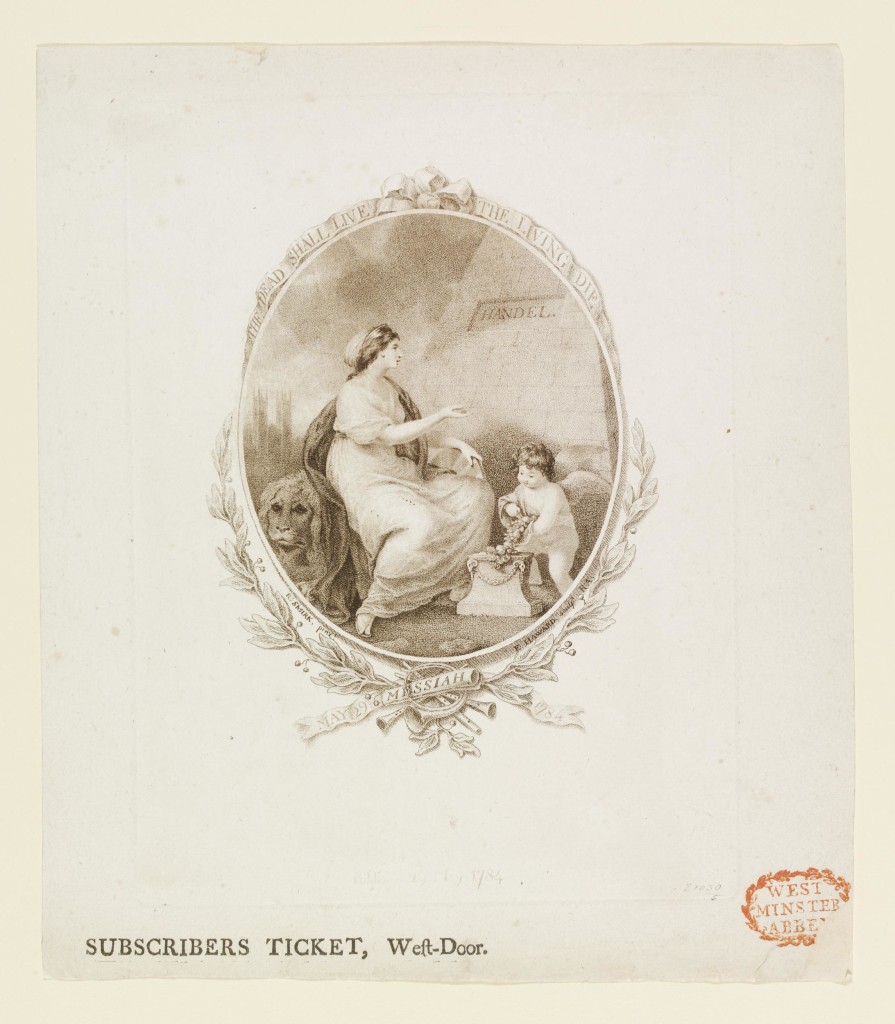

This ticket relates to the design E.1228-1948 in respect of the principal figure at the tomb but there are many differences. Image courtesy of British Museum.

An example of this can be seen in George Frideric Handel’s ‘Commemoration’ in 1784, which was an event to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the composer’s death. Symbolism in the design of the ticket utilised the popular motifs of the time, complete with religious symbolism in its mourning values. With art by Robert Smirke and engraving by Francis Haward, the inscription of ‘THE DEAD SHALL LIVE / THE LIVING DIE’ reflects chorus of Handel’s Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day (the following line being ‘And music shall untune the sky’). The female figure is once again flanked by the cherub, who is placing flowers on the plinth and has a sad expression. The female has a lion behind her, reflecting resurrection (as there was a belief of lion’s sleeping with open eyes having a comparison with Christ in the tomb) and the tomb to the right. Compare this symbolism and design with the following:

Dominant, square and pyramid shapes of the tomb refined down to the elements of the grave As can be seen in this 1849 memorial, the style is similar, but the stepped tomb is designed more like that of a cenotaph. Regardless of the elements, having the tomb displayed in a mourning jewel or depiction is an important connection to the loved one and their remains.

Alas! She’s gone

What jewellery does is display a personal sentiment to the world. Intentions of emotion, be they for love or status, are worn under the constructs of society’s values. These design elements are the values of a specific time, culture and religion; all the elements that are essential to a mourning jewel. Having a family depicted in a jewel, surrounded by these physical elements grounds the jewel’s design at the height of society and presents the family at the height of grief. Its large design and elements could be viewed by anyone to identify that the family was in mourning for a loved one.

This article has covered the static elements of the jewel, from the cypress, willow and tomb, as well as give context to how society had led to these values at the time. In the following article, we will be looking at the individuals, their fashion and their belief system, as well as comparing that to contemporary jewels and their designs.