A Hair Work Crucifix and Primary Sources in Mourning

Primary sources are the ideal way of discovering the history of an object. It removes the supposition, emotion and modernity which a viewer can place upon anything. In jewellery, the emotional level is set higher than many other objects, as they were built to resonate a certain feeling or sentiment and generate that within others. This makes it harder for any viewer, be it contemporary or modern, to hold a value upon a jewel which was quite personal for the wearer. Mourning and sentimental jewels only makes this harder. They are designed to provoke reaction beyond any other jewel. Their necessity is to define an individual’s status in society and to present that person at a certain time of their lives. Be it for a marriage, death, betrothal or family/religious establishment, the jewel is the pure version of identity that the wearer needs to convey within a society. Society did judge and was willing to impose its values upon a person who was required to be within a certain paradigm of mourning or social connection. If a widow was in society without the stages of mourning, jewellery or widow’s weeds in the 19th century, then it would be distasteful. In different points during the early-modern time, different ways of displaying oneself in society changed, but as industry and access to cheaper materials grew, the social implementation only became stronger. Driven by a Queen who imposed perpetual mourning on herself after the death of Albert, Prince Consort in 1861, the focal paradigm of fashion became locked into the presentation of mortality in society; something which became fashionable itself.

In terms of primary sources, the rise of the photograph and cheaper print/replication made the cabinet card with a subject wearing the same jewel that has lasted through time is a wonderful statement. While it may not provide further insights into why the jewel was created, it gives us a better idea of how it was worn and what the context was surrounding its wearing. This 14ct gold cross in table-woven hair it set with a single pearl at its centre. The photograph that accompanies it presents the lady wearing it at the neck upon a dress of black lace.

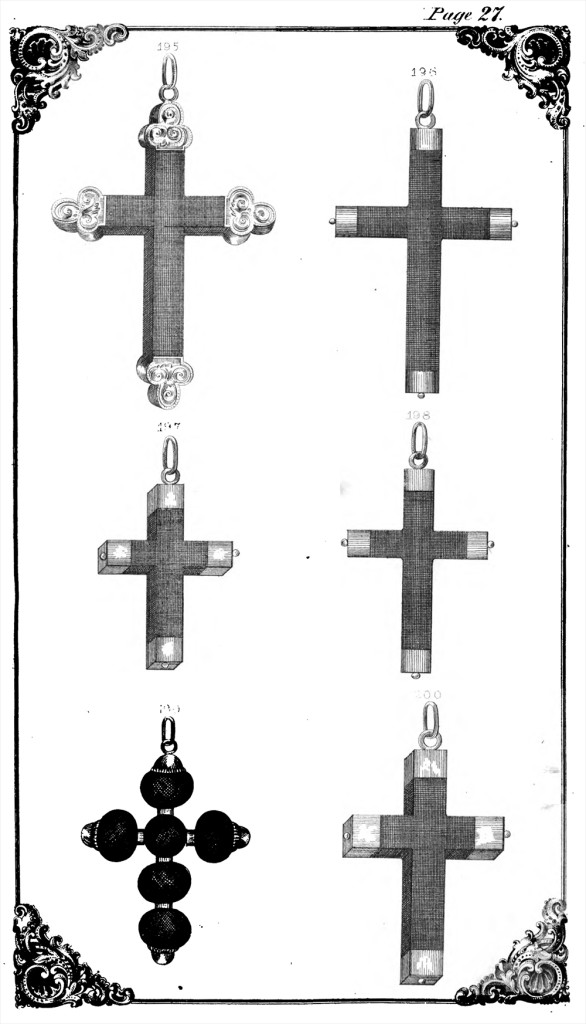

There is a reference to a nearly identical piece in Mark Campbell’s ‘Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work’ (1867) on the following plate of designs. Using catalogues is an ideal way of finding the origins of a jewel, as these show the global reach of a design and how it could be purchased in different markets.

Clearly, this is the more opulent of the crucifixes that could be chosen from a catalogue and the prices reflect this $10.00 for the mount and $15.00 for the completed piece is what the cross on the above left (195) cost and the reference for this article is different in that it houses the single pearl at its centre. Basic designs could be adapted and changed from catalogues, or replicated and personalised by jewellers. The basic template of the design is created and popular within Western markets, these being France, Britain and the United States.

Previous to the 19th century, society still had access to mass produced jewels, facilitated through better access to materials, and higher production through the Industrial Revolution. Primary sources and connecting people to their jewels becomes a lot more difficult, with paintings being one of the more typical methods of discovering the identity of the wearer and how the jewel was worn. From the 1760s, the Neoclassical movement changed the depiction of grief and love in sentimental jewels. The Neoclassical period was ushered in through the archaeological discoveries in Herculaneum and Pompeii, providing societies with genuine discoveries of societies locked in time. With the enlightenment challenging established socio/political/religious thought, the human element became the central figure of emotion. Classical art was represented with the person as the figure of grieving or a couple in love.

It’s very rare to capture a moment in time with any pre-photographic jewel, but that is what this stickpin does. It transcends the typical idyllic Neoclassical mourning depiction and brings the immediacy of mourning directly to the viewer. One is to assume that the gentleman seen in this piece is actually the person in mourning who wore it, which brings a tremendous amount of gravity to its message. Even in terms of wealth, this piece would be highly individual, but doesn’t show the quality of a perfectly staged miniature. It lends itself to a scenario that had an amount of speed in his creation, as the gentleman is in a common pose for a composition, but the coffin completely changes the composure of the scene.

We can assume that this would have been quite a realistic depiction for its time, as the modern viewer looks at what interment would have resembled in the 1780s, yet there is direction in its art. There is no background and only the simplest of textures given to the floor of the scene, with a hard line for the man to stand upon. This is the artist’s way of utilising the oval shape of the stickpin to their strengths, whereas a piece with an urn often suggest a place of burial if there is a dedication written under the urn on an ivory disc.

The woman, being the idealised romantic and symbolic centre of mourning for the family and the individual who would be wearing the jewels depicting grief, is the most standard mourning character of the time. Often wearing the white Neoclassical mourning attire, she is often standing or sitting next to a tomb or plinth, flanked with symbols of death and surrounded by the weeping willow. Often, these pieces were pre-created and sold with minor customisations to the person who acquired them, others, however, are of a higher quality and are purely commissioned for the person in mourning. These can be seen for their differences within the mourner herself; faces and costumes can often reflect the wearer and the jewel is almost a portrait, capturing the individual in a Neoclassical setting and depicting their grief.

The female mourner was an ideal figure for mourning identification in the Neoclassical period. She, along with her virtue, carried the fashion of the Greco-Roman period, with the typical high waistline and lower cut bodices is trimmed in white, with long, narrow sleeve ending at white cuffs. The figure’s hair is often framed with a white veil that is pulled back to reveal her hair (rather than the normal veil framing the face). When considered that these pieces were shown in public and messages of popular thought that could be propagated by their image, adaptation of popular fashion through people identifying with these jewels was natural. In the same way that a modern audience views an advertisement, these jewels self-replicated by their popularity and translated into rapidly evolving fashion amongst the wealthy. Everyone wants to be contemporary and these jewels carried a message of what was.

Understanding the fashion of the times and the context of how a lady is presented in a jewel can show the immediacy of the jewel to the mourner. Not precisely primary sources, those of higher quality become closely related to portraits, rather than an idyllic representation of a person.

Where we’ve seen the person as the figure of mourning, the following painting of Lady Christine Reede Gingkel (1802) displays her wearing the classical fashion of the day. She is painted to the classical ideal with her jewellery on display. When a portrait has the connection between the subject and it correlates to a jewel of modern times, the jewel’s provenance can be aligned. Much of the time, these kinds of pieces are very rare and match the wealth of those who could afford a portrait and the jewels. As higher production and lower grade materials could mass produce jewellery, access for jewels to the middle class caused a rift in primary sources and the jewel. It was only in 1840 and the advent of photography, along with its rapid development through the 19th century that cheap photography and cheap jewellery could align.

Photography is a major catalyst in the mourning industry. Memory was one of the only ways that every echelon of society could hold on to the image of a person, with miniature portraits having a high degree of cost and exclusivity. As cost lowered and technology led to faster production and smaller images, jewellery accommodated. As a primary source, the very subject of this article would not be possible without photography, making it fundamentally linked to the development of the mourning industry.

Early photographs were crude and the subjects were often not prepared correctly, but in a short period of time, the process was refined to studios and travelling photographers. As the style developed, the subjects became positioned and personal items of the deceased (or symbols of love) were placed around the body. Children are often the primary focus of post-mortem photographs and a great effort was made to make the subject look alive. For the photographer, making the subject look ‘asleep’ was one of the easier methods to do this, though studios specialised in ways to prepare the body for photography. These may be retainers to hold the bodies in position, massage to the limbs, rouging of the cheeks, ‘affixing the mouth closed with a forked stick placed under the chin and against the breastbone, closing the eyes with coins, and preserving the features by placing ice under the body.’ Different concepts were used in this method, but the primary focus was the same; to hold on to the memory.

“…parents evidently desired to represent their dead children in all kinds of attitudes in order to express their intense grief and their passionate desire to make their children survive in memory and in art, to exalt the children’s innocence, charm, and beauty.” Phillipe Ariès

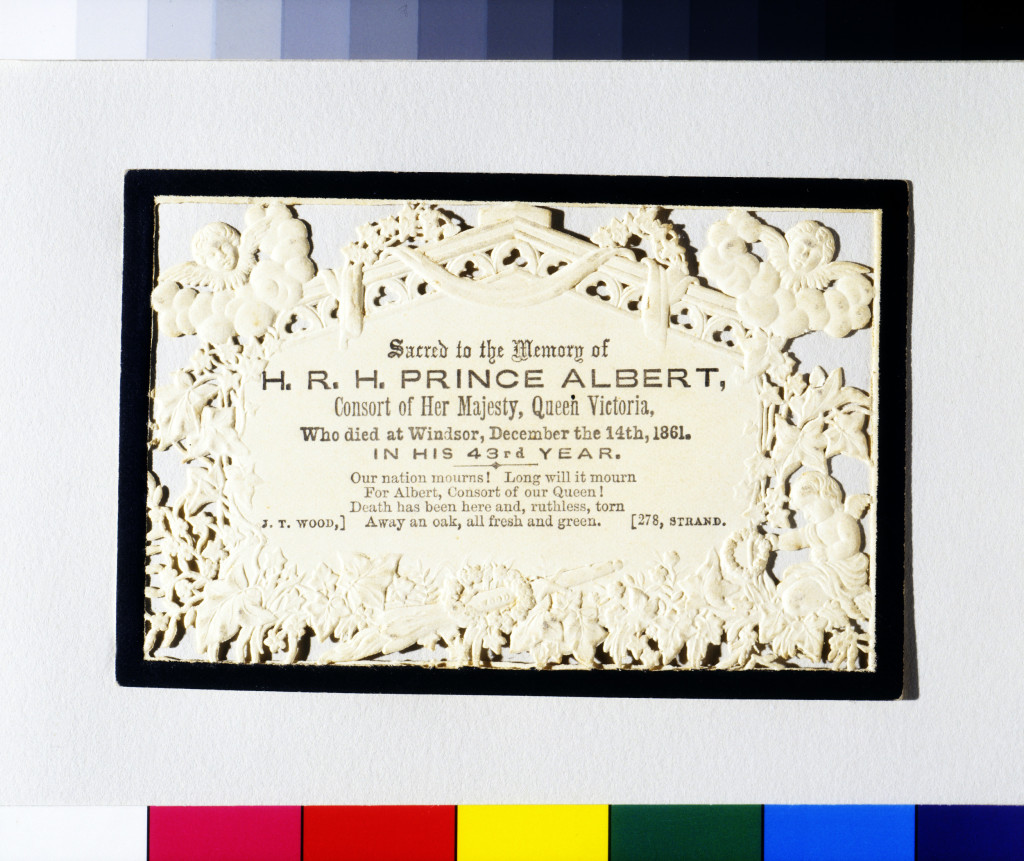

As print became affordable and accessible, items such as the Carte de visite and cabinet card were available with variations upon the post-mortem photograph. ‘Madonna’ images of the mother holding the deceased child, couples holding photographs of the deceased and more public cards showing the body of a famous person are all variations on the post-mortem photograph. One of the more interesting is the pre-mortem photograph, with the subject shown before death. This was an admittance of the mortality of the terminally ill by the family and these images are not prolific in the same way as their post-mortem counterparts. As soon as photography could be adopted as a viable means for mass print and accommodate customisation, memorial ephemera adopted the technology quickly. These often were images of the person in life, rather than in death, but the industry was large enough to adapt the photograph technology for different memorial purposes. Beginning in the 1860s, mourning (or funeral) cards are still used with personalised imagery today.

By the 1890s, post-mortem photography (as well as the mourning industry in general) was on the decline. Symbolism, such as the coffin, had replaced the body as the symbol of death and societies were distancing themselves from the image of death. Mortality rates were changing and the fact of death was evolving. Now, photographs were more inclined to show funeral arrangements or even the funeral itself. Perhaps the more melancholy imagery was that of the child’s empty shoes next to a memorial (though this was used during the height of post-mortem imagery as well). Post-mortem photography was kept until the early 20th century, yet more common were photographs of the deceased (while alive) used in memorials. The practice itself is a direct reflection of the family and incredibly personal to the family unit. Unlike jewellery or adhering to any form of mourning fashion to publicise the effect of mourning, the photograph held the memory of the person and should be seen as a powerful symbol of affection.

It is the relation of photography to the development of funeral and mourning/memorial cards that also brings together the subject of mourning and the person who holds a token of that. While jewellery was produced at high levels as stated in wills, memorial cards were produced at high levels and low cost, not relegated to the immediate family and friends.

As a primary source, cards in relation to the individual, be they for mourning or funerary practice, are very closely related to mourning jewellery. From their style to their message, they convey the sentiment of a specific period. Earlier, we saw the Neoclassical period and its influence of bringing the human element into the jewel itself. In this following funeral card from 1776, the anachronistic memento mori influence combines with the classical elements:

The card is lettered with the invitation at the centre of the design, reading:

‘Sir You are desired to Accompany the Funeral of Mrs. Rebecca Hale from Her late dwelling House at Lowlaten to the Parish Church of Totteridge on Saturday the 20th of April 1776 at Nine a Clock in the morning’

‘The Coach to Attend at Half past Seven a Clock in the morning’

‘Mr. Parle No.100 Upper Thames Street’

On either side stand the figures of a skeleton (Death) drawing a bow and three arrows and an elderly winged man (Time) holding an hour glass. Behind them is a black drape supported by two cherubs. At the bottom of the design is a funeral scene depicting mourners gathered round a tomb. At the head of the design is a coat of arms.

If anything, this provides an excellent insight into the physical requirements of establishing and attending a funeral. The language is formal and is very close to a modern invitation. It’s in the design where one can see a depiction of the people standing by the tomb in mourning and, while not a literal depiction, is a close approximation of how the procession would be.

It is the relation of photography to the development of funeral and mourning/memorial cards that also brings together the subject of mourning and the person who holds a token of that. While jewellery was produced at high levels as stated in wills, memorial cards were produced at high levels and low cost, not relegated to the immediate family and friends.

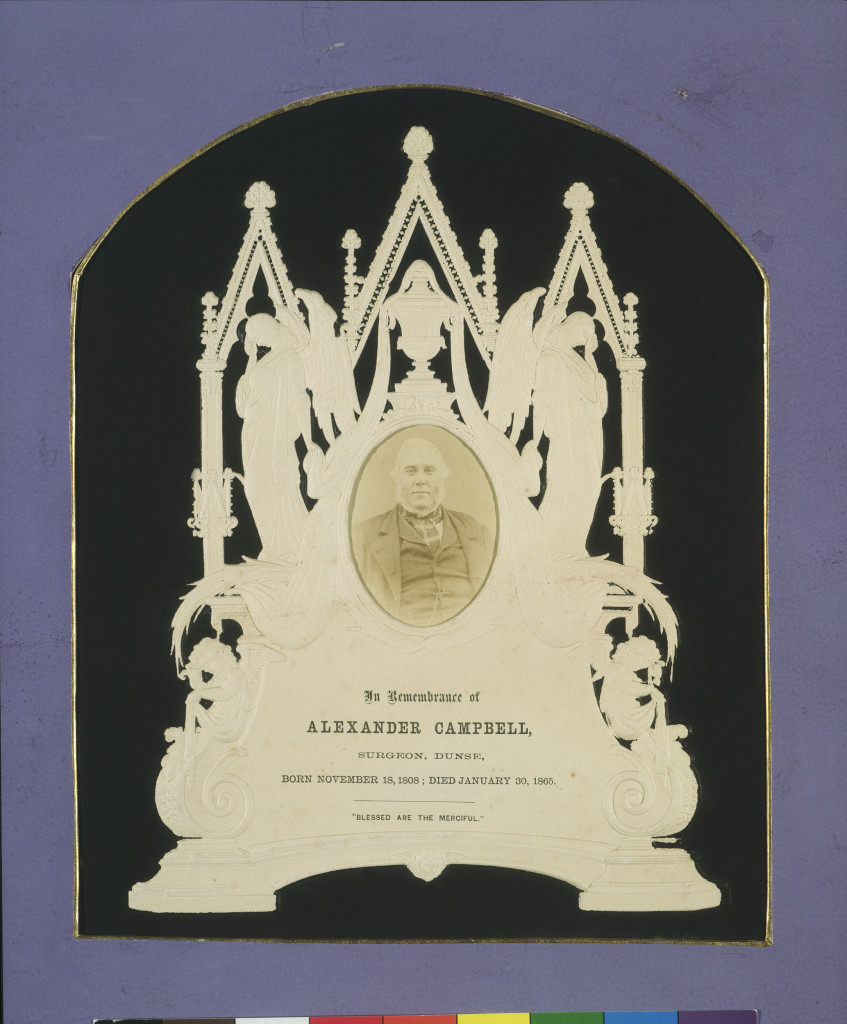

In the combination of photography in memorial cards, this superb example for Alexander Campbell (1808-1865). Ephemera from the mid-to-late 19th century was highly detailed and, even as production was high, it still required a high level of skill. In this instance, the card is embossed and pierced, involving hand-cutting a metal die and pressing dampened paper inside of the mould to create the required image. Larger cards were designed to framed and hung on a wall by friends and relatives of the deceased. This card measures 42.7 cm unframed at the height and 33 cm unframed.

Typically, printers embossed and produced the majority of the cards, with the dedications added later, much the same as mourning jewels. This is the same for other forms of ephemera, such as tickets, cards and other stationary. With the various styles that were popular during the Victorian period, elements of Rococo, Gothic and Neoclassical were common, as can be seen in this card.

As photography is a direct influence in this card, the understanding of a card becoming common practice in mourning needed to be perpetuated. The industry of the 19th century capitalised greatly on popular fashions and there was a hungry audience to purchase them.

It was the death of Albert that led to much of this industry being institutionalised and much of this can be seen in the lady’s costume, which is the subject of this article. Albert died in 1861, effectively locking Victoria in a period of perpetual mourning. The effect of this was felt within jewellery design, leading to a very static period for jewellery design in the remaining century.

But it was many of the social fashions that Albert introduced in the 1840s/50s that led much of modern Western standardisation. The family elements that were instilled by Victoria and Albert becoming popular in terms of literature and fashion. New challenges, such as Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, threatened the Christian family that had been established by Victoria and Albert, but fashion was still permeable. Romanticism flourished in literature and art, notably by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late 1840s. Looking towards medieval culture for inspiration and harshly turning against realism, many of the mourning and sentimental symbols that are common today in jewellery and funerary art were carried through by their use in art. Within literature, one must not look past Charles Dickens for the usage of Victorian sensibilities and values within his writing.

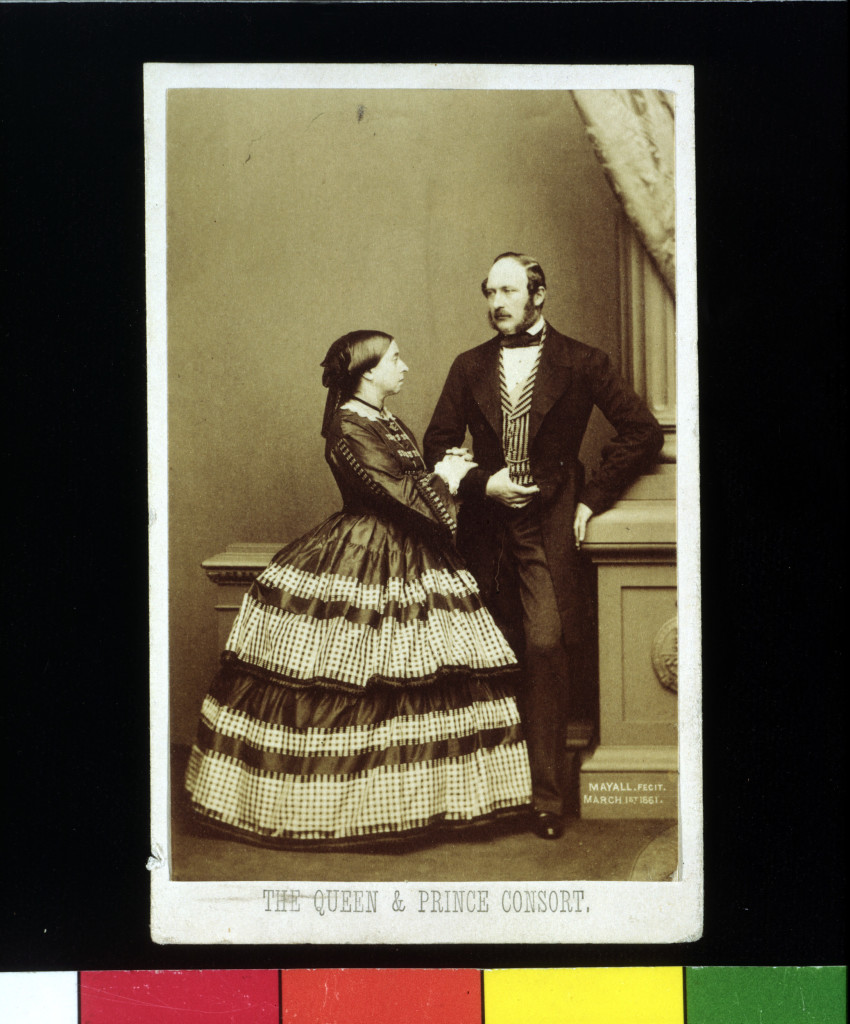

J.E Mayall gained a royal commission in photographing Queen Victoria and Albert, who passed on nine months after this carte de visit (French for ‘visiting card’) was taken. This photographic style is closely related to the visiting card, introduced in France c.1854, some being mass produced to the hundreds of thousands. Albert’s death generated massive interest in royal pictures, with those who purchased these images showing their public mourning and sympathies. This is an ideal way of presenting how a primary source can go between sentimental and mourning over the passage of time.

And so the industry of mourning grew and developed. Businesses could survive with the more tokens of affection that mourning required, as could new industries grow. Printing, crape manufacture, hair weavers, jewellers and goldsmiths all benefitted from newfound interest in the fashion of mourning.

Capitalising on death is not a new concept, but one that began in pre-history and continues today. It’s within the messaging of what happens in the afterlife that creates a fear and a need for others to capture a memory. In today’s example of a hair crucifix pendant and the lady who wore it, we see the need for a token of affection to house a memory.

This memory has continued and lasted to now, where it becomes part of the present owner’s collection and this memory is retained. We have seen the likely place where the pendant was purchased and originally designed, through to the primary sources that have led to mourning growing through technologies. The catalysts that drove the mourning industry are all related to fashion in popular culture and the need for identity in a world that was growing smaller through better mobility.

Essentially, however, the memory is captured in the pendant and the photograph. All of these elements led to the creation of these things, but they had no conceit other than wanting a token of love and affection for the purpose of memory.