Charms, Chains and Bracelets

Charm bracelets defy the typical aesthetic convention of wrist jewellery, due to their ability to adapt, grow and completely contradict a singular reason for existence. Their invention is intrinsically linked with the Victorian period, due to the popularisation of the charm bracelet through Queen Victoria, however the stringing of various tokens of affection and memory to a central unifying piece of jewellery is an ancient practice. For as long as humanity has cultivated relationships and developed interpersonal ways of forging a memory, the ability to create a moment through a piece of jewellery is locked in. A piece of carved bone may represent a moment of love or victory, therefore it is something which can be kept as the keepsake for that moment.

Understanding that popular fashion in modern culture is created through a method of control from a dominating body for the sake of conformity in society through identification, it is easy to understand why the charm bracelet as a concept became popular in the 19th century. Queen Victoria was the one to popularise mourning, through her love of fashion and the adaption of the industry towards her perpetual mourning following the death of Albert, Prince Consort, on the 14th of December, 1861.

Victoria wore this bracelet until her death in 1901, where it was part of a group of jewels placed in the ‘Albert Room’ at Windsor Castle. Prince Albert had died in this room and the Queen left instructions for a specific list of personal jewellery to be placed there and not passed on in the family. Each locket contains a personal memento of hair or a photograph for family, which can be seen through the dates and inscriptions upon the lockets themselves. There is a consistent theme with these jewels, as Victoria maintained the heart symbol as her preference, but this wasn’t standard for the common charm bracelet.

In the Paris Exposition of 1889, TIffany & Co premiered their chain link bracelet with a heart-shaped pendant, elevating the status of the charm bracelet into modern sentimental fashion. Finance was coming from a new source that was not the aristocracy and influencing the development of new jewels. It was the financiers who made this development possible. At a time when new wealth could define new styles, going beyond the previously established family-based old money, Americans began to spend their money in Paris, leading to the rise in jewellery production houses and their proliferation. Tiffany & Co. developed by this money and presented their quality work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900. Notably, their contribution to jewellery development was the Tiffany Setting in 1886; a diamond setting above a ring which lets in as much light as possible to the stone. René Lalique, whose influence to Art Nouveau is exponential, was awarded a Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition, leading to the popularity of delicate, organic styles in jewellery design and development. Methods, such as the Plique-à-jour enamel work (meaning ‘letting in the light’), were fundamental in how jewellery design was reacting to the previously consistent styles that had represented the late 19th century.

With rapid development of new styles of jewellery through artists which were being paid to create challenging jewels, the charm bracelet took a new life that lasts to today.

Victoria’s influence in establishing the charm bracelet began earlier than Albert’s death in 1861. As with much of the early-modern fashion, the Crown would introduce an element of fashion and the aristocracy would imitate it and it would cascade down through society.

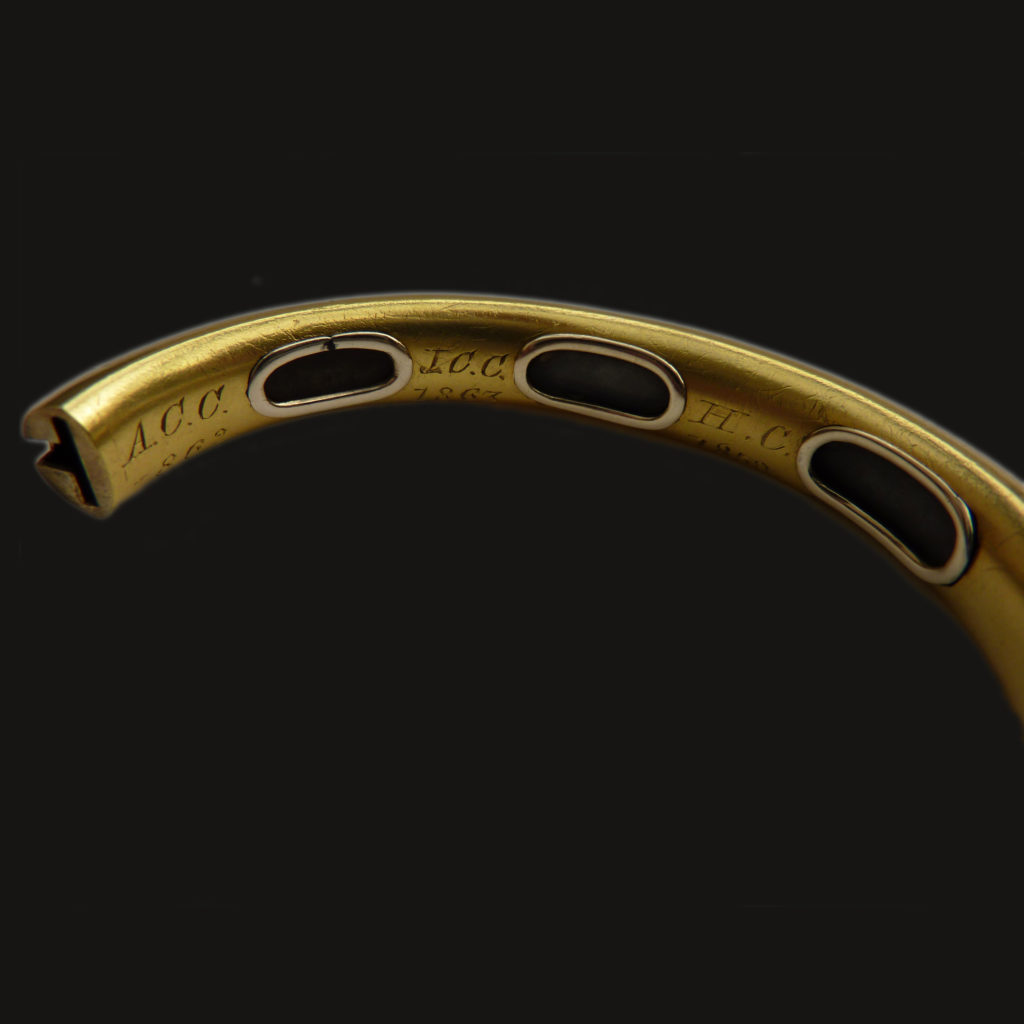

Also placed in the ‘Albert Room’ is this exceptional bracelet. Utilising the common heart motifs, it contains the hair of Queen Victoria’s children. An inscription inside the bracelet states that it was given to Victoria three days after the birth of their first child and a locket was given for every birth after, containing a lock of the child’s hair and the date of birth inscription. The following inscriptions state:

“Pink for Princess Victoria, turquoise blue for Albert, red for Princess Alice, dark blue for Alfred, translucent white for Helena, dark green for Louise, mid blue for Arthur, opaque white for Leopold and light green for Beatrice.”

The occurrence of such a gift is only going to resonate through a society which is susceptible towards craving fashion from a monarch. Victoria was highly sentimental in her fashion, popularising hair and the tokens of love enough to create an industry. In the Paris Exhibition of 1855, a life-size portrait of Queen Victoria was created in hair, a worthwhile homage to a queen who appreciated the sentiment of hairwork so much. Indeed, with such a cultural importance on the value of hair as a material, the French were the epitome of style and to use such a material in a gesture shows just how widespread hair was used in mainstream fashion.

The uniformity of Victoria’s family bracelet is impressive, in that it retains the heart motif throughout, while changing the colour of enamel. In most circumstances, the colour of the enamel would indicate a different symbol of sentimentality (black for death, blue for royalty), but these work as an aesthetically pleasing piece of jewellery to be worn at the wrist. Jewels for birth don’t follow the same conventions as those of mourning, as the tokens of affection given for a childbirth aren’t defined by more than their size (many jewels were created in small scale for children) or their family sentimentality. Victoria’s bracelet shows the simple nature of love and affection, while also being a planned jewel, as the future hearts were created upon the births of her future children.

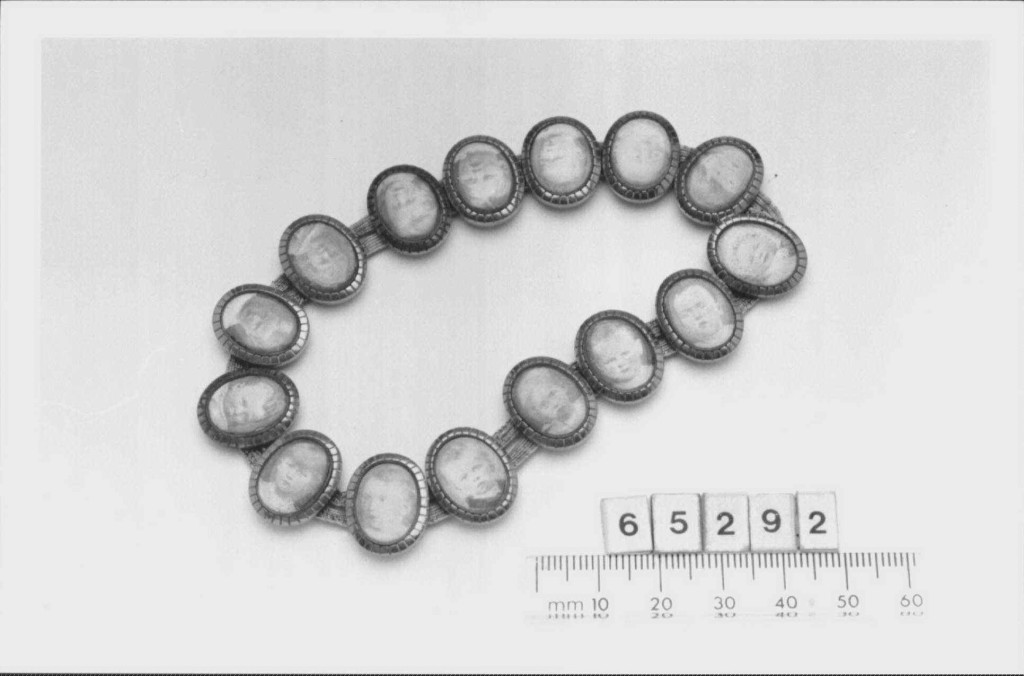

For her grandchildren, Victoria wore this bracelet of fifteen oval painted photographs, set in gold, with the names of the children on the reverse. Being later in the 19th century when photography had overtaken other methods of memorials due to their low cost and ability to capture the sitter nearly instantly, this bracelet shows Victoria’s adaptation for change in sentimentality. It is fashionable, but still retains the quality of a love token that she had in her youth.

While remaining singular in her concept of sentimentality and how that should be represented, Victoria did change and adapt through fashion. The imposition of this within society after her imposed mourning period was more difficult to a wide population in order to adapt towards that fashion and became emblematic of the Victorian period itself.

Seen here is Victoria’s first locket, which was a ‘Present from her Mother to her beloved Victoria on the First Anniversary of her Birthday 24 May 1820’. It is not difficult to see the continuity in the preference of Victoria’s charms being related to the heart from this locket. The Duchess of of Kent, Victoria’s mother, essentially set the standard of sentimentality which would permeate society through popular jewellery in the preference of what resonated with Victoria.

At it’s most basic, the locket is a charm. How it was worn, be it a pendant or at the wrist, is the opinion of the wearer, as charms can be worn in multiples or in the singular. Why charms are so popular is that they can be a collection of memories granted over a period of a lifetime and worn and keepsakes of a moment. There’s no ceremony that requires them to be worn for a period of time, nor is there a bequeathment of love that is a necessarily a pact between people in society. There is only the thought that counts.

Seen in this bracelet is the combination of multiple charms that have overtaken the bracelet itself. There are memories kept in ever charm, from the locket to the car; this is a collection of memories that are so personal to the wearer that they can only be interpreted with supposition from the modern viewer. Once the life of the wearer is finished, unless these memories are recorded and past down through the family, there is little to hinge the nature of the charms upon, unless they can be traced to their manufacture.

High production levels in the 19th century meant that from a catalogue, a piece could be chosen and ordered from around the world. Identifying jewels between a culture such as the United States or United Kingdom can be difficult, as trade passed freely between countries. Not only did the charms pass between countries, but so did people. High movement of society through travel meant that acquiring a charm during a vacation would be a typical way to capture the memory.

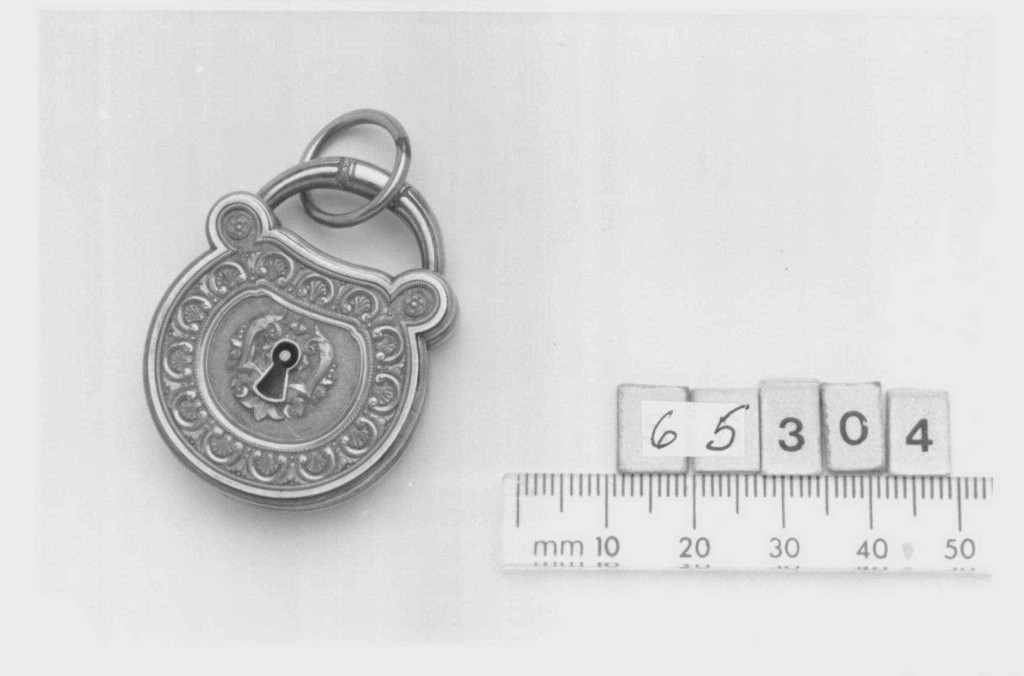

Seen in this simple locket given to Queen Victoria by the Duchess of York in 1900, the sentiment of giving a charm was not lost by the end of the century. Victoria was near the end of her life, yet the giving of gifts remained the same as it did since she was born. Consider the continuity in the preference of the lock as a symbol and a token. Combined with other charms, it is the connecting element in charm jewellery, being the lock that ties the other symbols together. Combined with the multiple charms seen in the earlier silver example, it remains the most basic charm design that is still in production today. Charm bracelets are essentially the large interlocking links and the locket itself. Given as a charm on its own, it is a sentiment of a way to create new memories. Tiffany & Co produced a locket in 1889 created its iconic charm bracelet with a single heart for the Paris Exposition Universelle. Charms, such as the padlock with the Tiffany & Co branding, are still in production today.

Size and scale of the charms is an important factor in their creation. The Hallmarking Act of 1854 that allowed the use of lower grade alloys. Reflecting this upon the larger styles of female dress, jewels could be larger and lighter to wear. Finding rolled gold bracelets that seem heavy, but are very light, is typical for the post 1850 period. Charms themselves need not be high in gold or silver quality, but some were adorned with gems or paste to add an extra element.

Charms as accessories on chains from Alberts to chatelaines were typical of tokens of affection in daily wear. To see how charms worked within the context of daily fashion, looking to a hair fob chain with its charms is a good example of this.

There are several elements here that are intrinsic to Victorian style and fashion that represent the person, that involves not only hairwork, but symbolism itself.

With this fob chain, a fashion accessory that was as essential to men’s fashion as would be the presentation of mourning (though this is a sentimental piece), there are pieces which combine to create a whole. There is the pearl, the garnet, the acorn and the hairwork, forming a union between symbolism and material that could be used as a part of daily fashion. But why was it constructed, how was it constructed and why was it worn?

Let’s first look to the fittings, the first thing that a collector should be analysing. Here, we have signs of wealth, due to the use of the pearl and garnets, as well as the bespoke charms. It should be noted that this is requested by the person who bought the piece, as each element could be chosen from the catalogue to assemble the desired combination of sentimentality for the chain. A gentleman’s accessory was built around the fob chain, as this housed many of the essential elements for daily use, such as the pocket watch, hence the use of hairwork is the primary element that draws this back to sentimentality and its purpose in late Victorian culture.

WIth higher catalysts for change in fashion during the 18th and early 19th centuries, the latter 19th century had a very fixed view of mainstream fashion, with many underlying and peripheral art movements growing in their own right. Yet, just because movements happen over a period of time (such as the Arts and Crafts movement), this does not mean there is a clear change in fashion over a short period due to a single event. Generations grew up with the paradigm of fashion (royalty) dictating the nature of fashion and with Queen Victoria remaining in mourning from 1861, we have expansion of an Empire at an exponential rate, but only elements of this showing through within the culture. This is within the areas annexed and bought into the British Empire that could influence the culture (such as India); everything from food and fashion was affected by this. Though there was bleed-though from to the tastes of the aristocracy, it did not affect the proper nature of what could be worn at court or presented as the fungible way in which a person presented themselves in a passionate way, be it mourning or sentimentality.

Hence, this is why such a simple fob chain can be seen as a culturally important element of daily life for its time. This is how a gentleman would be presented and the smaller pieces to this fob chain reflect that persona.

The fob chain is an important as it was functional and defined fashion. Indeed, men’s fashion could be discerned by the number of button holes that shown the provided the anchorage for the chain. This would denote the number of accessories attached to the chain, and hence, the wealth of its wearer by the number of accessories and how the tailoring of the costume could be defined around it.

“The way in which watches have been worn has changed ver the years and they are as much an indication of wealth today as they were in the sixteenth century. From the time of Henry VIII it was fashionable for a monarch to wear a watch as a pendant at waist level. A skilled watchmaker could even make the watch in the form of wring. In the seventeenth century Samuel Pepys reflected in his diary that how a watch was worn gave an indication of the wearer’s character. Since its invention the watch, with its chain and attachments, has been the most decorative item worn by a gentleman. From Georgian times the chain was worn diagonally with a bolero style of vest (later called a waistcoat). The chatelaine (an ornamental chain hanging from the waist to which ,keys, seals and similar objects were attached) was worn by both men and women at this time and the skills of jewellers and goldsmiths were lavished on it.” (Gentleman’s Dress Accessories, Eckerstein, Firkins, 1987)

Wearing chains is important for status as much as it was for function. Combining a charm with the chain relates it to being more personal for the wearer. The acorn was a popular charm design, so after seeing Victoria’s heart and locket charms, this is a good way to balance how people presented themselves within society through a symbol in a charm.

Found as a charm on fob chains and bracelets, the acorn is often seen an ancillary motif in jewellery, balancing other symbols or complimenting a mourning sentiment, but more rarely being the prominent, singular motif used for a piece. The strength of the acorn and its potential to grow is a personal statement of fortitude, which can be seen in both male and female charms.

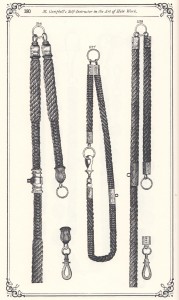

Often seen on military tombs, the acorn can stand for power, authority or victory, however it is also a statement of longevity, strong new growth and new life. Charms were found in many jewellery catalogues of the time, as can be seen in the following pages from Mark Campbell’s ‘The Art of Hair Working’ (1875):

The fitting and the charm could be chosen from the same production house, along with the choice of hair weave. From its fitting, we can approximate it to figure 256, which shows the undulating pattern to the the charm clasp and the Rococo Revival pattern. Note that the style of the fitting is fundamentally important to identification in these fob chains. An incorrect assumption could throw out the date of a chain by over thirty years, and in an era of very heavy standardisation, this could change the purpose and perception of the jewel.

The eight-square chain braid is another factor in the quality and how its construction is important in hairwork and as a token of affection:

“TAKE sixteen stands, eighty hairs in a strand, and place them on a table like pattern. Commence at A: take Nos. 1 strands, lift across the table and lay down inside of Nos. 1 at B, and bring back Nos. 2 from B to A; then lift Nos. 3 from A to B, and bring back Nos. 3 from B to A; then lift Nos. 4 from A to B, and bring back Nos. 4 from B to A; then commence at Nos. 1 again, and repeat until the chain is completed.

Braid this over a small wire, with a hole in one end like the eye of a needle, so as to draw a small cord in the place of the wire. When you have it braided, take off your weights, tie the ends fast on the wire, and push the braid together; then boil in water about ten minutes; then take it out and put it in an oven as hot as it will bear without burning, until it is quite dry; then take it out and slip it off the wire on to the cord, sew the ends of the braid so it will not slip on the cord, and put a little shellac on the end to keep it fast. If you want it elastic, use elastic cord. To vary the size of the braid, vary the number of hairs in a strand.”

There is a rhythmic complexity in the braiding of the chain and quite a lot of hair used shows how the effort of the love token not only aids its strength in construction, but the thought of the sentiment that the wearer would represent for their loved one.

Be it silver, hair, gold or a base metal, the simplicity of the chain is the fundamental property that holds a charm. Different symbols can combine around the body to establish a narrative of character. These personal elements are defining who their wearer is and still remaining transparent and fashionable for people to view and admire.

It’s within their personal sentiment that the preference of the wearer is established, be that for an element of luck (seen above in the horseshoe), through to religious sentients of crucifixes. Charms can be designed and produced at high volume and low cost, so it would not be uncommon for a traveller to purchase a memento of an occasion and fix it to their chain. As with the earlier silver bracelet, there is a thick narrative of travel and experience, be that in the dolphin or the car charm. Their random nature can be as prescribed as Queen Victoria’s appropriation of the heart, or they can be a confluence of messages that might trigger a memory in the wearer.

Affordable and instant tokens of love are the true nature of the charm. They have the ability to delight and create a beautiful item of reflection that can be held close at all times. Fine jewellery can be worn, and indeed jewels were only appropriate for specific times a day, a a charm doesn’t need to be delicate or orchestrated. Much like love itself, the charm is timeless and will always have a place in fashion.