A Guide to the Stages of Mourning

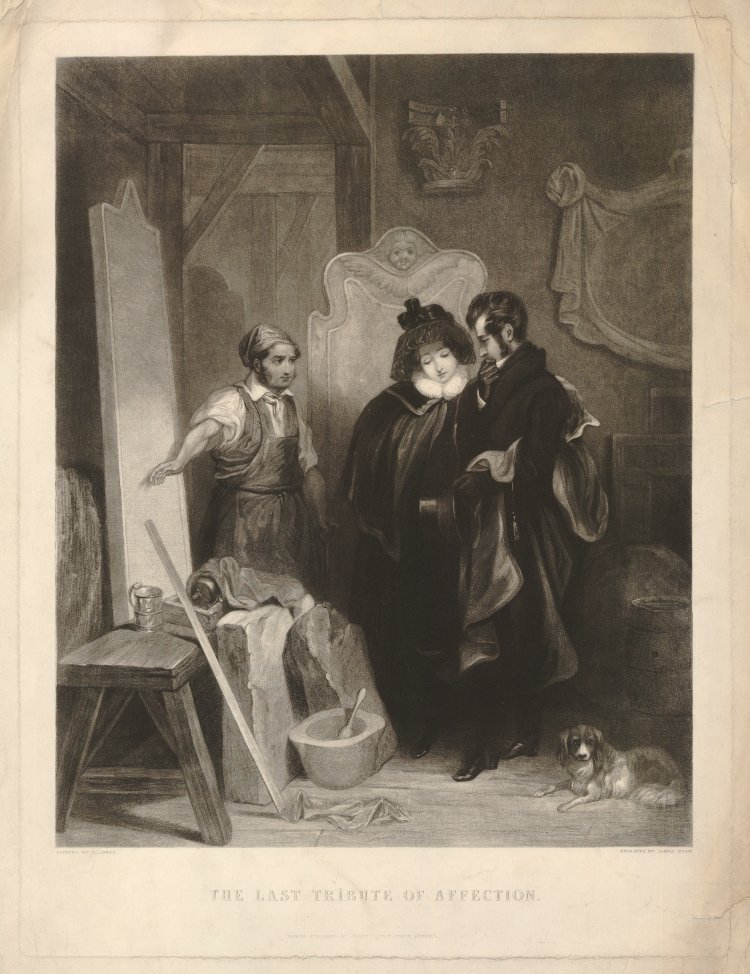

Grief is automatically triggered by loss as part of our psychological construction. Mourning, in its most pure form, is a period of transition for a loved one to understand the loss and accept the memory of a person. Stages of mourning in fashion and identity are generally separated into ‘deepest mourning’, ‘second’ / ‘ordinary’ stages and the ’third’ / ‘half’ stage of mourning, as ordained by Court. Each of these periods required different fashions, colours and materials to be worn for acceptance in society. A mourner would represent the family and be expected to uphold the values of that family, hence adhering to these stages was important throughout the early-modern period. From the 17th century, the massive impact of the Protestant Reformation had taken its toll on European society and forced many cultures to question traditional values of faith. This destabilised monarchies and established internal conflicts which held on to new or traditional value systems. When faith is challenged, so does the concept of the afterlife and what happens to the soul. How people represented themselves within these different factions came down to fashion and personal tokens of affection. Mourning jewellery grew from this; it was a way to represent the values of the mourner and the consideration of mortality itself.

Combined with a high mortality rate, conflicting values blended well with the growth of industry. As societies became more mobile (such as the Protestant influx from Europe into England), skills also became mobile and jewellers and dressmakers established themselves in new territories. With new discoveries and trade routes into Asia and abroad, the 17th and 18th centuries saw the development of the mourning industry, as commerce could grow with an exploitable market. Death is a function of existence that can be used at a high level for control, business growth and market specialisation. From a more immediate level, the items that businesses create to provide for the sake of mourning all give the mourner a token of memory for a loved one. It is a symbiotic relationship that’s mutually beneficial.

Governments, particularly in times of political instability, can utilise a public mourning period to mass produce materials for a departed monarch, aristocrat or war hero. Jewels and peripheral items made for Princess Charlotte in 1817 led to a mass production of accessories and mourning items due to the massive public outpouring of emotion for her. Lord Horatio Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar denoted an important milestone in British history with the victory over Napoleon’s forces being symbolic. When a public event is referenced by a government, its significance is remembered, to the point where a memorial item might be replicated in future times to reignite the memory of the occasion and what it means for cultural unity and identity. Nelson’s mourning rings have been replicated on the anniversary of the battle and once more, the memory retains.

In the case of these events, it is necessary to wear and behave in a certain way to express unity and solidarity. In times like these, Court mandates over what to wear during mourning become required and that mandate bleeds through to the rest of the public. The three levels of mourning aren’t enforced from a legal perspective, but they are socially correct.

Deepest Mourning

Matt finishes and non-reflective surfaces are an incredibly important factor in mourning, which is a psychological manifestation in jewels and fashion. This transcended fabric through to household items in order to indicate that a house was in mourning and respect the afterlife.

In the Greek mythology, Narcissus was the son of a river god (Cephisesus) and a nymph (Liriope), who was known for his beauty. With his pride, he ignored those who loved him, which was exploited by Nemesis (the spirit of retribution against hubris). Nemesis invited Narcissus to a pool, where he saw his reflection and fell in love with it, eventually not leaving this beautiful image and drowning.

Sir James Frazer (1854-1941), a social anthropologist, was fascinated by this fable, and in Narcissus: Myth and Magic (1906) wrote about the importance of the reflection and its connection to the soul. The article’s abstract;

“Proposes that the Narcissus myth is connected to a form of divination known as scrying. Stance of literary scholar James Frazer on the relationship between myths and rituals; Discussion on the scrying ritual; Sources of the myth.”

Linking the soul to reflection is important in understanding why the first stage of mourning was necessary for both the mourner and the deceased to remain as plain as possible. Mirrors, photographs and portraits were turned to the wall or covered after death and reflections avoided. Jewellery would thus have a matt finish to shed to reflection.

During the deepest period of mourning, women wore no jewellery, as mandated by Court rules. Though the rules of Court were applied to it, the fashion of its rules became popular. Men were to remove all shoe buckles, watch chains, swords and buttons. In the mid 18th century France, these could be replaced with bronze accessories, but the rule was to replace all with accessories that had a matt black finish.

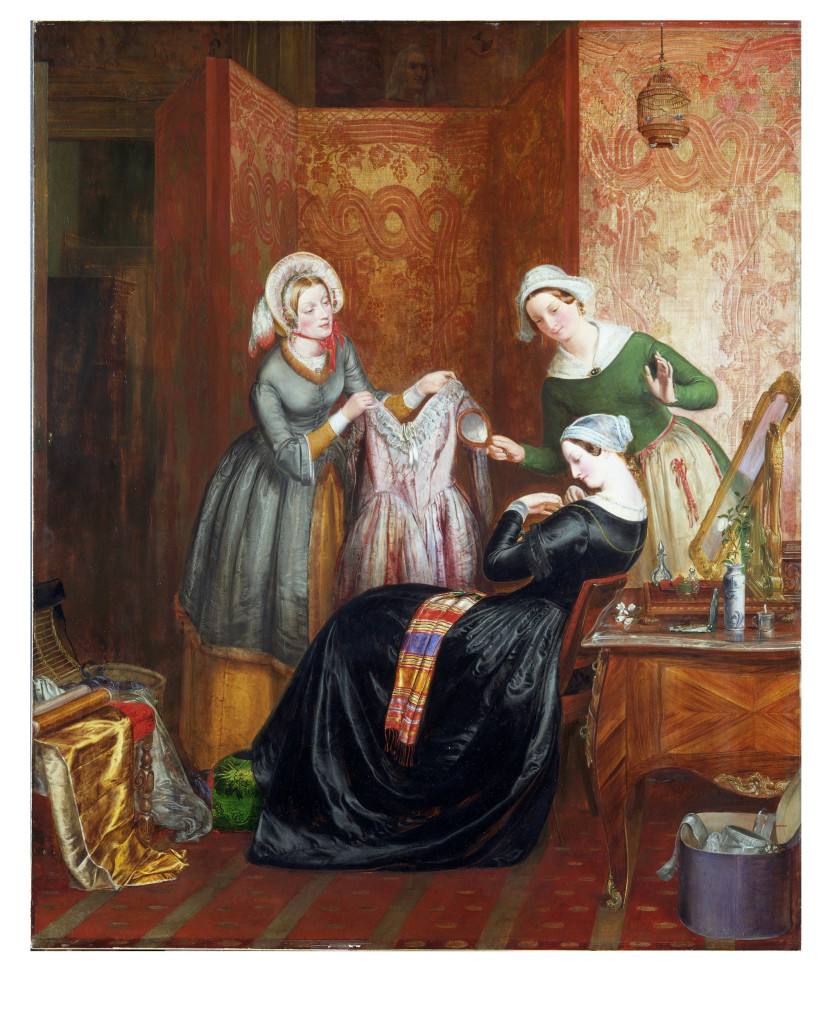

As seen in this portrait of the Duchess of Bourbon from 1702, she appears in deepest mourning and is not wearing any jewellery. While not exclusive as a formal ritual, Court mandates were fashionable, so the rules could be broken and not undermine the convention of not wearing jewels. A mourning ring in deepest mourning would not be uncommon, though the first stage was considered the most important previous to the 19th century.

Fashion and presentation of identity in mourning is closely related to the creation of a community. Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), whose diaries show a great insight into culture at the time, have a great insight into several funerals throughout his lifetime and the impact fashion and cost had in his life. Pepy’s Aunt Fenner died on August 1661 and Pepy’s father carried out funeral arrangements. As his father was a tailor, the family could not afford to purchase mourning for relatives, but instead tailored it themselves. The sentiment he wrote was ‘all in mourning, doing him the greatest honour, the world believing that he did give us it.’ Another aunt died one month later, with Pepys and his wife wearing the same garments, making him write: ’To church, my wife with me, whose mooring is now grown so old that I am ashamed to go to church with her.’

For his own mourning jewels, in 1703 Pepys ordered 46 mourning rings at 20 shillings, 62 rings at 15 shillings and 20 rings at 10 shillings. These rings were given to friends, family and acquaintances at the funeral, as was the standard of the time. by doing this, it relates back to how family and friends could present themselves in society during the stages of mourning. The custom of giving out the ring at the funeral was not typical in the 19th century, but was relegated to close family.

During the 19th century, rules became more convoluted. A mix of reasons led to this high level of detail, ranging from the value of the mourning industry and economics, through to social control in an unstable environment. Economically, there was a mourning industry that became a legitimate strength in its own right. Machine power was the proponent of having mourning fashion be affordable and attainable. George Courtauld, in conjunction with Joseph Wilson, converted a flour mill in Braintree, Essex, to manufacture silk yarns and crape gauzes. This was established in 1809-1815, with silk-throwing, steam-driven machines being tested in 1827 leading to 2,000 local workers being employed and notorious for a fine coloured silk known as ‘aerophane’. Between 1835 to 1885, profit grew from £40,000 to £450,000. Courtaulds employed a great number of women in the Finishing Department of the process and was notorious for its labour force, which also employed children against the 1833 Factory Act.

£40,000 to £450,000 is a major leap in a short period of time and shows just how powerful the mourning industry had become. Economics also led to new materials and concurrent industries to link into the mourning industry through fashion and mandate. Jet is a good example of this, as in Sylvia’s Home Journal it was stated for a widow in the first year of mourning (1881) that ‘no ornaments except jet’ could be worn.

By the 1870s, the annual turnover of the Whitby jet industry was said to be over one hundred thousand pounds, with a jet craftsperson earning between three and four pounds a week. From 1832, there were only two shops employing twenty-five people to 1872, where two hundred shops employing fifteen hundred women, men and children, taking over the landscape of Whitby. Development of machinery, such as the lathe, also helped to facilitate the growth of jet production meeting the high public demand for jet pieces. However, demand was so high that soft jet was imported from Spain and France, mainly for beading (as previously mentioned, soft jet tended to crack and many surviving pieces reflect this today), giving the jet trade what was considered to be a ‘bad name’, hence the attempt in 1890 to trademark ‘Whitby’ as a quality of jet. Jet was also seeing great competition in lesser-quality imitations which were far cheaper and by 1936, only five craftsmen were left. By 1958, the last Victorian trained jet carver had passed on. Clearly, economics has a role to play in the introduction of materials to the first stage of mourning.

Mrs John Sherwood wrote in Manners and Social Usages (1887) that ‘diamond ornaments set in black enamel are allowed in deepest mourning and also pearls set in black’. Diamonds have been used for the second stage and beyond in jewellery much more typically. By the late 19th century, fashion and mourning had become closely linked, with a mortality rate which meant that some mothers would spend their lives in mourning, the trappings of fashion needed to adapt to some of the finery that not being in mourning could afford. It was much of this regulation that led to the decline of the industry, which a lack of adaptability and change over a long period. Women were the heart of the family and the central ideal for mourning representation. This was challenged through the static nature of mainstream fashion and led to the rise of other arts movements influencing contemporary fashion.

From 1900, there was a significant split in jewellery styles. Court-worn jewels were still based around the Rococo Revival style and using highly privileged, material-based gems, such as diamonds. This was normal around European Courts and remained consistent from the 19th century. In Europe, the organic influence of Art Nouveau and its use of coloured gems and enamel became popular. The Arts and Crafts movement flourished in Britain as a response to mechanisation; bringing back a return to traditional crafts. This remained consistent up to the beginning of the First World War.

Deepest mourning is a practice that is still held in regard today. It is the instant reaction to the death of a loved one and the elements, such as wearing black, are natural reactions to death.

Second / Ordinary Stages

During the 17th century, the Second and Ordinary stages of mourning allowed for only black and white gems. Much of the symbolism of gems and custom of wearing them came from early-modern standards of wearing fashion and custom. Pearls were particularly fashionable, so their colour and integration into mourning fashion had its origins early. Much like jet, the introduction of a material or allowance for fashion in mourning works well with industry.

Discovery and trade led to the desirability of pearls, particularly from medieval and Elizabethan times. ‘Oriental’ pearls, originating from the oyster family, were the most desirable due to their lustre, which pearls from freshwater mussels and conch shells do not have. The Oriental pearls were bought to Europe form the Persian Gulf by caravan traders.

As with deepest mourning, the industry led to influence in fashion. Popularity of pearls reached their height in the late Georgian Era, where clusters of seed pearls were sewn to mother-of-pearl backs with cat gut, some examples can be seen below from the British Museum:

The various sentimental tokens seen here are typical of the late 18th century and would be quite fashionable in their context. How could a the mourning industry adapt these styles to be fashionable for the second stage of mourning? Below is a perfect example with the urn encapsulated by the pearl border:

Yet the pearl may have been more accessible in the 18th century. but its history grew from the 17th century.

The below portrait of Anne of Denmark from 1612 shows her in morning for her father, Frederick II of Denmark. She is in deepest mourning, with only the smallest amount of white trim added to her collar and the rest of her costume being non reflective.

At her bodice (on the bottom right), notice the mourning brooch. This is the traditional way of wearing the brooch, which became at the neck during the 19th century. She is wearing black stone tear-drop earrings as well as the fashionable pearl. There’s a delicate intricacy in the combination of fashion seen here; it’s simplicity is elegant as is the balance of black and white. The portrait painter takes this into account, as the brooch is even disappeared from sight in the muted colours; referencing how jewllery was worn, but is respectful of being in mourning.

By 1760, Court instructions allowed for ‘white necklaces and earrings’ and the catalyst for this was Second mourning for George II. Court rules were defined by the death of a monarch or a leader, as these are the moments that capture the attention of an entire population. The allowance for ‘black fans, feathers and ornaments’ came from the death of Prince Albert in 1861. Second mourning consisted of black dresses, trimmed with fringed or plain linen, white gloves, black or white shoes, fans and tippets and white necklaces and earrings as necessary. Grey lusterings, tabbies and damasks were acceptable for less formal occasions.

19th century jewels are more difficult to identify, when considering them as mourning or sentimental jewels. The fashion was quite similar and so were materials. Pearls, hair, jet and many of the symbols that were used for mourning were fashionable as well, so it’s best to only decide if a jewel was for mourning. In the below ring, the elements of the gypsy-set pearl and the woven hair in the band are typical of a loving sentimental token.

Black enamel dominated the styles of the 19th century, leading to greater standardisation of jewels post 1840. This was a combination of industry growing large enough to build itself around mourning and skilled production houses capitalising on it.

Particularly when hair is used as the primary material in the 19th century, the catalogues which they are identified through focus on the weave of the hair or its fittings. Jewellery which has been made as a marriage between two pieces or has lost some of its elements can make something as beautiful as a hair necklace or fob chain difficult to identify.

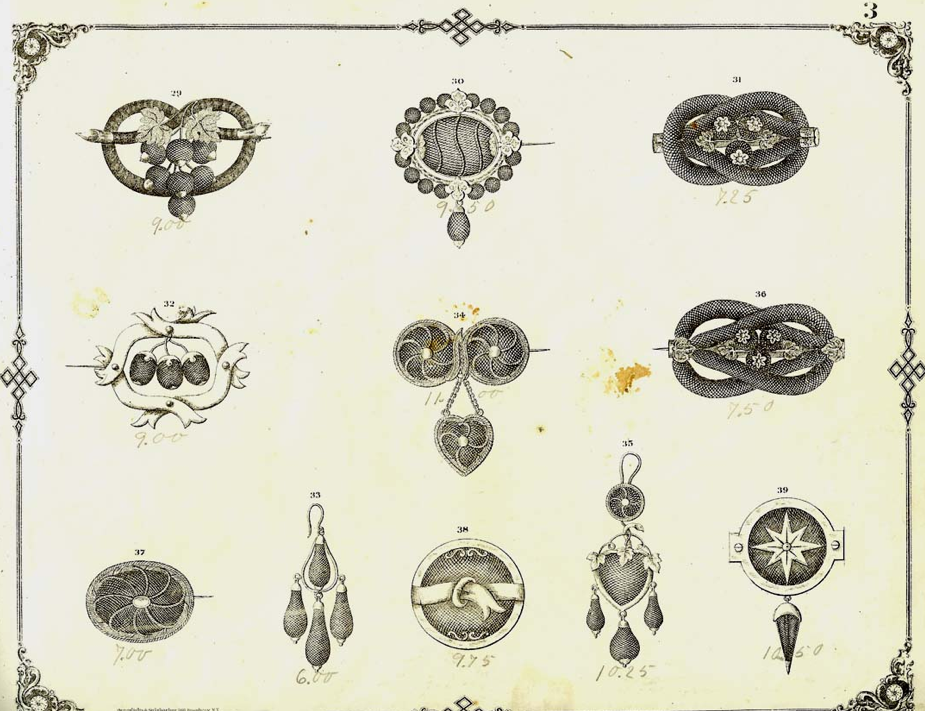

In the case of these earrings, the below catalogue page clearly identifies their style at the bottom:

The very notion that a catalogue could produce such a variety of hairwork jewels speaks back to the culture that required them. Hair was a popular statement of love and identity. It did not need to be a statement of grief or excess of affection, but simply a loving statement within fashion. This related to the professional catalogue and the home itself. Hairwork could be done within the household, as Mark Campbell’s Art of Hair Working (1875) shows. Having something of a keepsake of a loved one to weave into fashion, even if it’s just a basic twist of hair in a locket is a basic way of keeping love close. Given that mobility was high in the latter 19th century through mass transit, hair and photography were at the height of popularity.

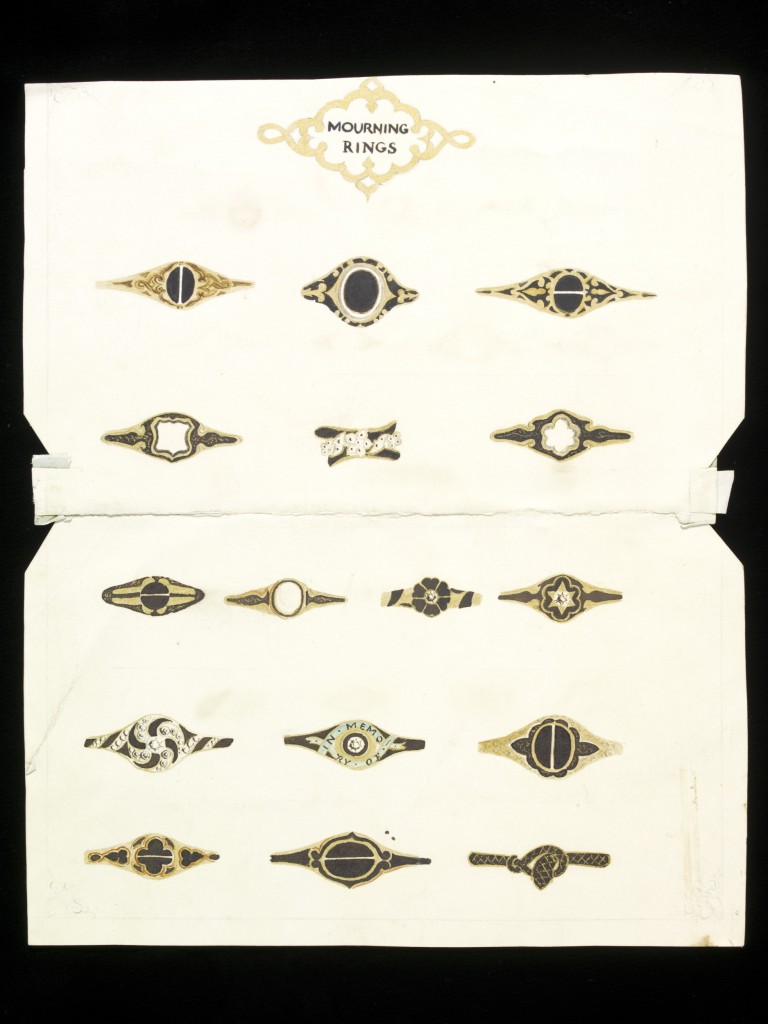

Black enamel bands are the most recognised of mourning jewels, being placed in very visible positions for others to see, easy and cheap to manufacture and all for the purpose of creating the wearer to be a walking tombstone for the person who is deceased. Their ability to be re-appropriated or kept by a family lineage is important, as these rings are far more important as tokens of remembrance and genealogy, as opposed to their commercial value.

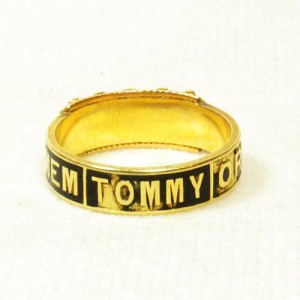

By looking at two different eras of mourning rings, we will see their importance as cultural markers. The following ring is from 1827:

And this ring is from 1881:

What can be gathered from the two different eras, times when the meaning of mourning and the imposition by Court values created the necessity of mourning?

Firstly, the design of the ring speaks in volumes to the society within which is was created. The first example from 1827 has the excessive flourishes around the edge of the band which were incredibly popular in jewellery design of the 1820-40 period. This was ushered in through the Gothic Revival period and its use of the Rococo styling that was can be seen in architecture (such as cornices) and furniture design. Its use, combining floral and acanthus motifs, are decorative and dominating, imposing a style which was opulent upon a society that was moving away from the excess of the Regency Era and towards the simpler pre-Enlightenment Christian values. Dominance in style is a reflection of the majesty of God and final judgement, where a life lived in piety would be rewarded with entrance into heaven. This is a motif worn on the finger to show the values of this for the deceased, who is in this case William Wrightson.

Compared to the 1827 ring, the 1881 piece is reflective of Victorian standards, where design was simplified and direct; the sentiment is drawn to the top of the ring, where the gypsy set pearls are inlaid to the stylised buckle. Post 1870s mourning jewels are far more streamlined to the Empire style, which was influenced greatly by classical elements of Roman, Greek and Etruscan in the late Victorian era, yet retained the simpler elements of each. Note the pieces below:

Enamel is one of the most important factors in mourning jewels, denoting at what stage the jewel would be worn in the three stages of mourning custom, clearly denoting that the jewel was created for the purpose of death and also the status of the person wearing it within society.

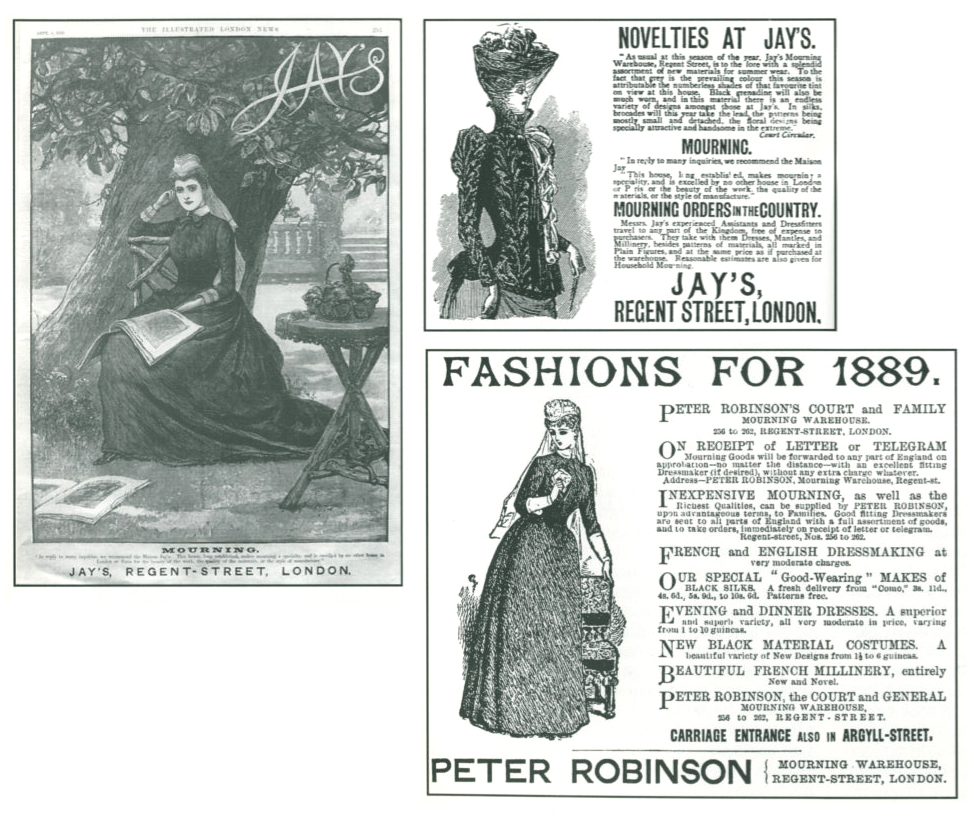

Black enamelled rings were easy to create with low gold content and make in great numbers. The producers in Chester, Birmingham, Exeter, Newcastle, Sheffield, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dublin and London could supply Britain and its colonies with a large supply of rings that were transported for the purposes of mourning. A jeweller colour simply tailor the ring for the individual, or a mourning warehouse (such Jay’s; see below), could supply all the products necessary for mourning to a family, including the rings.

However, we see in this ring for Tommy, that the ring was quite bespoke:

In 1881, we have the standardised mourning Victorian style, yet we have a personal statement etched into the ring. For construction, this was the concept the ring was built around. Unlike many other rings with the ‘mother’ and ‘father‘ titles pre-made into the band and created within a series of different sizes, this ring was made to order by the person in mourning for Tommy. ‘IN MEMORIAM TOMMY’ would be a set pattern that ‘Tommy’ was adapted to, rather than being a completely new design. Granted that ‘Tommy’ is a five letter name, the design could accommodate other names if the jeweller had to make another bespoke jewel for another, hence other rings may exist with similar designs.

Introduction of more identity, material and colour into the second stage of mourning was important for personal growth through a grieving phase. It was also a way to reconnect with a non-grieving society and wear elements that reemerged the individual back into this society. Consider that Queen Victoria never left mourning and many of her trappings post-1861 were more inclined towards this phase of mourning in the household.

Third / Half Stages

Third and half-mourning allowed for ladies to introduce diamonds into their costume, but incrementally. Gentlemen could change their buttons from black to silver, as well as buckles and swords. The third stage, introduced after twenty-one months, involves the omission of crape, inclusion of black silk trimmed with jet, black ribbon and embroidery or lace were permitted. Post 1860, soft mauves, violet, pansy, lilac, scabious and heliotrope were acceptable in half mourning. This period lasted three months.Women could wear black silk and velvet, coloured buttons, fans and tippets and plain white, silver or gold combination coloured stuff with black ribbons. Men could wear white, gold or silver brocaded waistcoats with black suits. The rules set by Lord Chamberlain crossed Europe, the United States (from the 1860s / 70s) and colonial territories, but Court mourning was longer than General mourning. General mourning was growing in popularity due to the accessibility of mourning costume and the cost.

Third stage mourning for Albert lasted from the 17th of February to the 10th of March, 1862. During this time, women could introduce ‘pearls, diamonds or plain gold and silver ornaments’ to their costume. Accessories were also popular, as with all public mourning, there was an industry to capitalise on the death.

Contemporary opinions of what constitutes for a mourning or sentimental jewel are often based upon modern understanding. The wearing of hair for a loved one is ancient, but many today find the practice morbid. For jewels that were made through the early-modern period, the introduction of hair in jewellery ranges from being a nice love token or a trigger of memory. When combined with colours in gems or enamel, it must be considered if the jewel is a third or latter-stage mourning jewel or if it was just a love token at its inception.

Seen within this brooch from 1860, the dedication reads “To D.H.R from her affectionate mother.” The brooch is not worn for mourning purposes, but a loving gift from a mother to a daughter.

Official mourning guidelines issued by the Lord Chamberlain decreed that black velvets and silks were permissible in the third and final stage after the death of Princess Charlotte and the above dress from c.1823-25 shows the early integration of the third stage of mourning.

Colour theory for the third stage of mourning is important to factor into jewellery wearing and social reintegration. This period has much flexibility based around how long it was standard to be in the ordinary stage, due to many remaining in mourning if for a husband, wife or child. To combine the sentimentality of mourning into daily lifestyle, the use of gems and other colours to integrate with hair was a way of wearing the loved one in a way that wasn’t completely disassociated with society.

Amethysts are a good way of integrating mauve into jewellery fashion. Through the 17th to 19th centuries, jewels created post-mortem to be used as a memorial token and used as a keepsake were typical. Jewels made for the earlier stages of mourning, or dedicated to a person in the will, could be added to with other materials in order to show the movement from deeper mourning into the third stage.

Other materials, such as turquoise were incorporated, but as with fashion, it must have a dedication or peripheral symbol or statement of mourning to be considered a third stage mourning jewel. It is hard to define how these jewels were worn or created within a specific period, as many who lose a loved one never do let them go, so for the rest of their life, they continue to commission jewels or tokens of love and remembrance.

Final Stage

There really is no final stage to mourning. The culmination of all these stages show that people love and want to be loved. A relationship is a series of mutually shared experiences and when the one who has shared those experiences passes on, then those experiences become memory. Memory is triggered through the things we have around us, from the smell to the sight. Jewellery helps this memory along, with the keepsake worn on the hands, wrist and chest triggering a thought.

Of course, commercial aspects understood the benefits of creating these tokens of love and governments knew that they required a holistic identity that could connect people together. As these industries and societies grew, so did the culture of mourning and the memory.

The 19th century has given modern times many of its standards that we take for granted today, but the tokens of love in fashion has been largely forgotten. Perhaps the daily items we have and the technologies we use have replaced them, but their elements are still part of modern identity.