Watches, Chains and Accessories

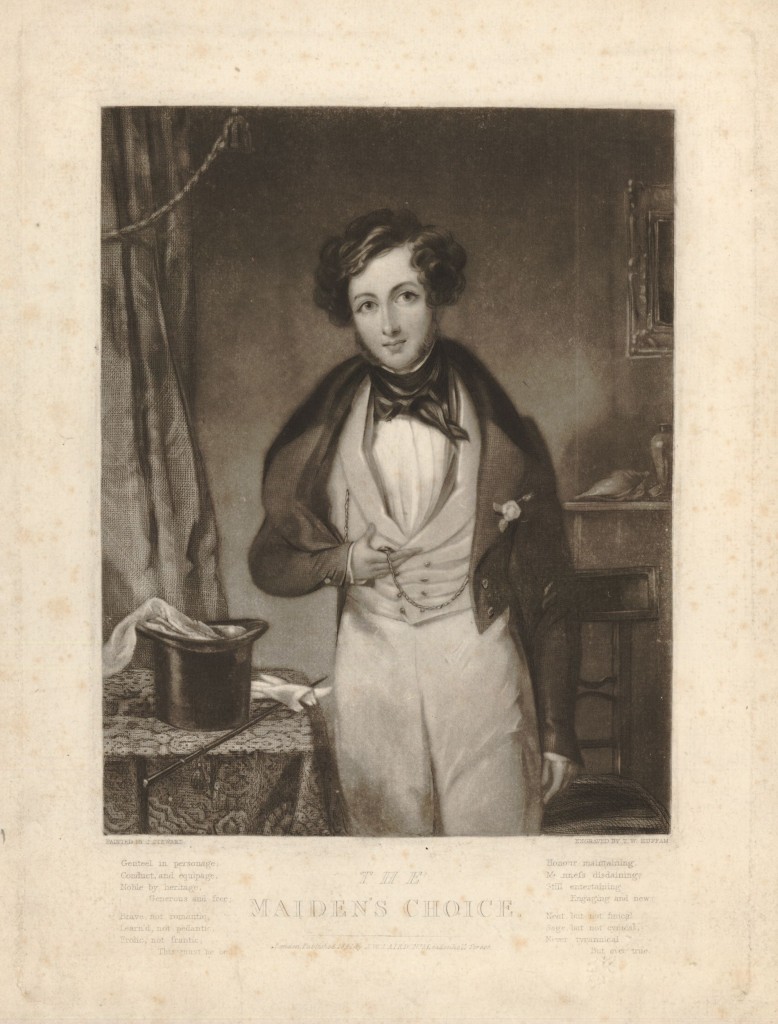

Sentimental accessories show just how important the Romantic movement was within the fashion of 19th century society. Many peripheral accessories for costume and daily use were produced, from Albert chains (chains buttoned into the waistcoat through a T-bar with watches and other accessories attached), to chatelaines and stick pins; the daily tools of usage were attached to the body for access and use. Utilising these accessories as functional objects which were also fashionable, hair and gems were infused within these items to produce a memento of a loved one and a keepsake for memory. Previous to the 19th century when the amount of accessories that adorned the body wasn’t so robust, items such as watches were decorative items for an affluent society. Many were engraved or moulded into sentimental shapes, such as the memento mori watch below:

The watch was a great catalyst for the advent of the popular wearing of the chain. From the time of Henry VIII, wearing a watch as a pendant near the waist became a fashion. On January 1-2, Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), the noted diary writer wrote on January 1-2 1668 “..and took coach and home about 9 or to at night, where not finding my wife come home, I took the same coach again, and leaving my watch behind me for fear of robbing…”, indicating the importance of status to wearing such a timepiece on the body. Affluence in the timepiece demands an equally adorned chain to hang it by. By the 18th century, the waistcoat/bolero was the popular form of wearing the watch, diagonally across the body.

While the chatelaine was also worn with equality between men and women; its development and craft lent by the influx of Huguenots emigrating to Great Britain. This was when the previous allowance by Henry IV of France provided Calvinist Protestants (Huguenots) significant rights. With this retraction, the Huguenots bought with them skills which enabled the London trade to compete with Paris. This led to greater patronage with the influx of greater designs and new elements of fashion appearing as popular in jewels. By the mid 18th century, much of the values that were carried to Britain were instilled within the new industry and led to such elements as the Rococo designs in jewellery from its continental influence.

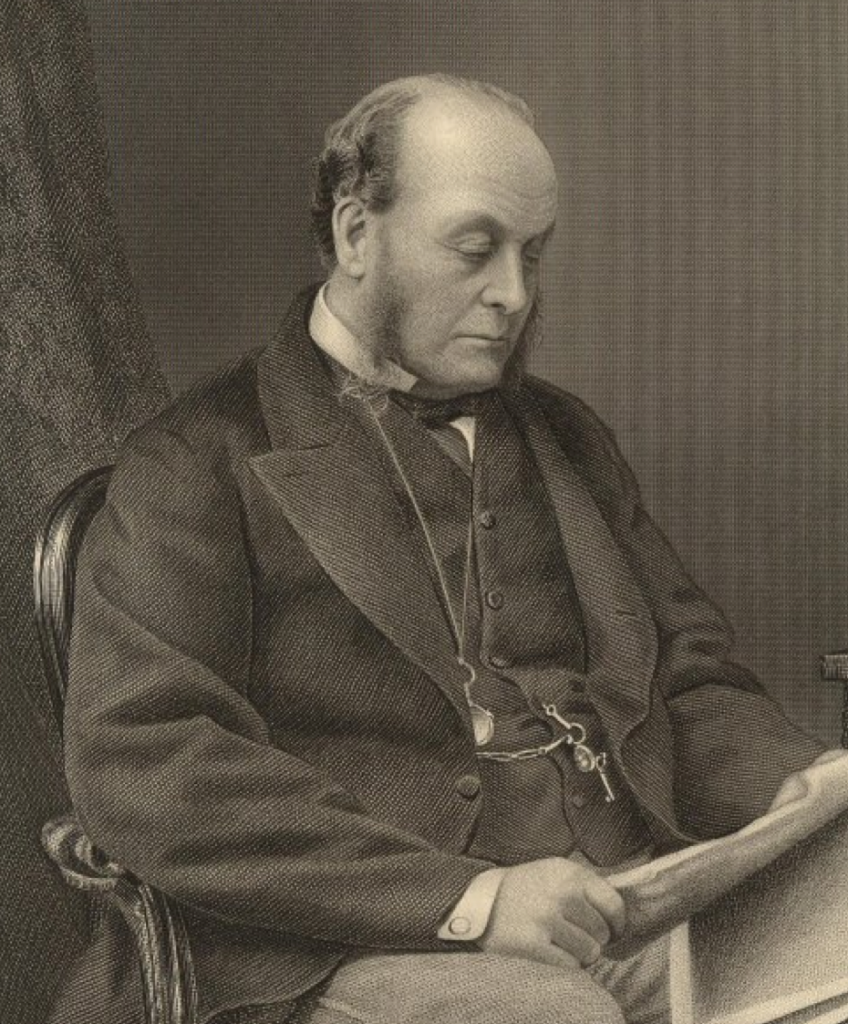

The name of the Albert chain comes from Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert (1819-1661), who wore his chain horizontally, attaching it from right pocket to left. Albert’s influence on Victorian society, culture and art cannot be overlooked, as it was through innovation led by Albert, that industry developed and produced many of the items that would be used in day to day life and also attached to the chains. The Great Exhibition of 1851 came about during a time of European and Latin American economic turmoil in 1848, leading to revolutions following the rise of nationalism. Albert’s dedication towards acknowledging the underprivileged and offering financial and educational assistance was an incredibly bold stance for the time, particularly when his family in Europe was being threatened.

Since 1843, Albert was President of the Society of Arts, which, from its annual exhibition, became the basis for the Great Exhibition. Based in Hyde Park within The Crystal Palace, the value of science, art and industry became a matter of pride for British society, which is a progressive step and one that shows the great innovation of Albert, himself. As a counter to revolution, The Great Exhibition stood fast and as a catalyst for art and innovation, the impact upon jewellery design that was revealed through new techniques of metallurgy and style resonated back through society.

The 1850s led much of this standardisation, with the family elements that were instilled by Victoria and Albert becoming popular in terms of literature and fashion. New challenges, such as Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, threatened the Christian family that had been established by Victoria and Albert, but fashion was still permeable. Romanticism flourished in literature and art, notably by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in the late 1840s. Looking towards medieval culture for inspiration and harshly turning against realism, many of the mourning and sentimental symbols that are common today in jewellery and funerary art were carried through by their use in art.

Within literature, one must not look past Charles Dickens for the usage of Victorian sensibilities and values within his writing. Albert died in 1861, effectively locking Victoria in a period of perpetual mourning. The effect of this was felt within jewellery design, leading to a very static period for jewellery design in the remaining century. Bolder style was in its element during the 1860s. This can be attributed to the mourning of Queen Victoria from 1861, but also tells of the evolution in costume and everyday dress. The larger styles of the mid-Victorian era had taken hold, with female fashion becoming larger and the jewels needed to adapt.

Through accessories, the use of monogram medallions, sovereign cases, charms, compasses, pencils, lockets and vestas and emblems became the focus of the gentleman’s fashionable identity, all attached to the chain itself. For all the elements that the Victorian period bought into fashion, the accessories adapted to it, be that for mourning, romantic or decorative purposes, the chain was the tool for wearing and exposing the identity of the gentleman, at a time when fashion remained static.

The fire agate used in this watch charm lends to the high usage of chalcedony as a sentimental material that was set in all forms of jewellery. Chalcedony is a term that refers to many varieties of cryptocrystalline quartz gemstones, ranging from sard, plasma, parse, bloodstone, onyx, sardonyx, carnelian, agate and many more. Early human use has been found for knives, tools, vessels and other such primitive tools. Later examples carried through history, from the creation of cylindrical seals in Mesopotamia in from the 7th century B.C.E, through to Mediterranean-based civilisations in buttons, cameos and intaglios. For these brooches, one must consider the necessity of the style in fashion and how this material could benefit its use in jewellery.

As is the case with many influential materials in jewellery construction, the access to cheaper materials often define the style which comes from it. The town of Idar-Oberstein became popular in the 19th century for its processing and carving of Chalcedony, with cheap importation of mining from Latin America. Due to its history dating back to Roman times, Idar-Oberstein provided raw agate and jasper, with a lapidary industry appearing in the 15th century to finish the materials.

Agate as a material for sentimental use is often for health and longevity, which relate well to the sentimental nature of the woven hair on the reverse. It’s the connection between two people for a happy and long life together; a token of love that is used on a daily basis to wind the watch and remind the wearer of the one who is far away.

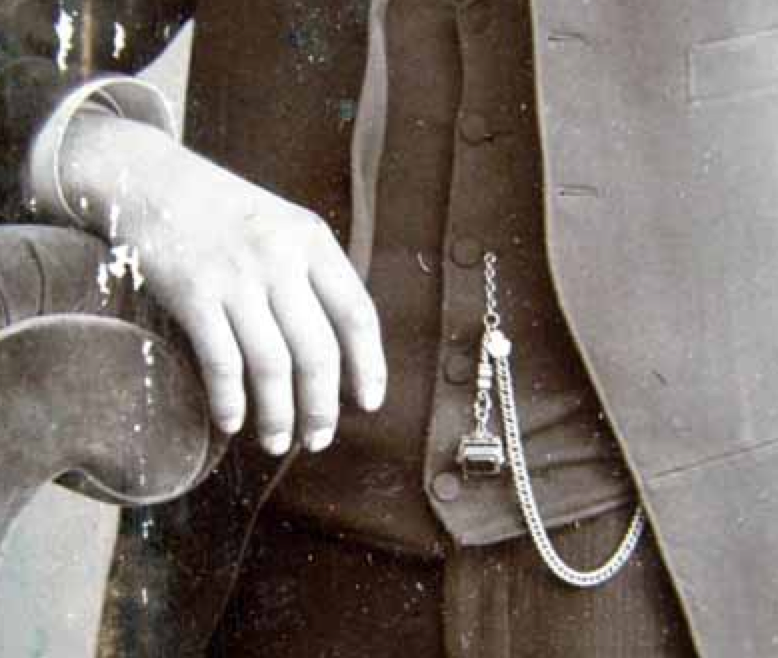

Misnomered as the fob chain, the fob was actually the small pocket in the waistband of a gentleman’s breeches that held the watch. Seals are referred to as the ‘fob’, which many 19th century examples show as being highly decorative in gold, silver and Pinchbeck or brass with similar inlay of stones.

Seen in the above example from the, this fob would have been worn exposed. DeLorme describes it as:

‘This fob is actually in the form of a “watch,” and is full of memorial symbolism. In the scene we see a severed weeping willow tree trunk with two branches growing from it, symbolizing that although the marital union has been broken in death, it still grows and lives eternally. This is literally true of the willow itself, which will grow from severed branches. Two birds overhead form a lover’s knot with a ribbon, also signifying marital union and love. The inscription reads “The further away the closer together,” typifying the romantic belief in love existing after death in the “life to come”. The fob swivels by pressing the nob at the top, and reverses to show the plaited hair of the man’s wife. 2.5”’

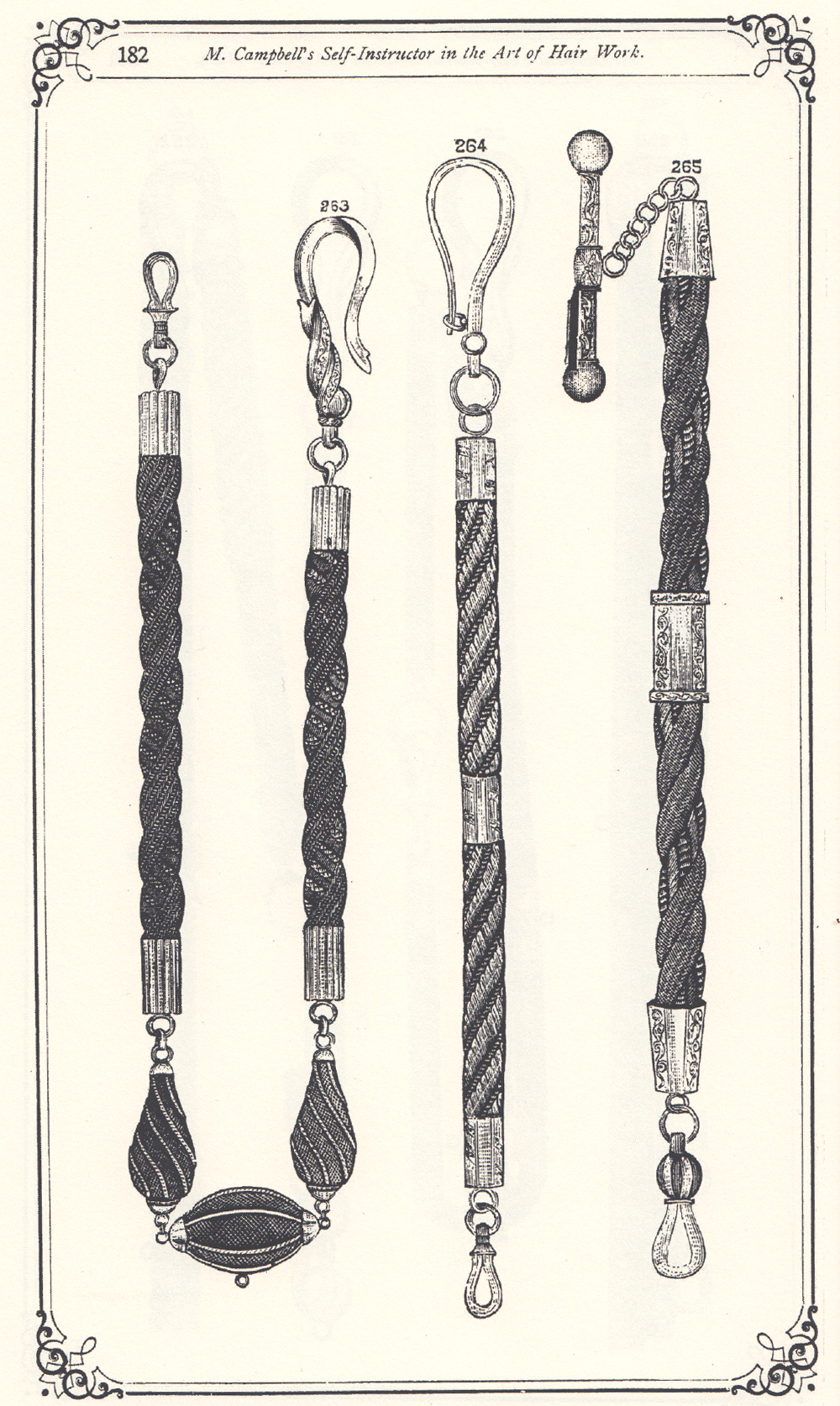

While the following 19th century locket in the centre of the hair chain is more typical for a sentimental signifier in the watch chain for display:

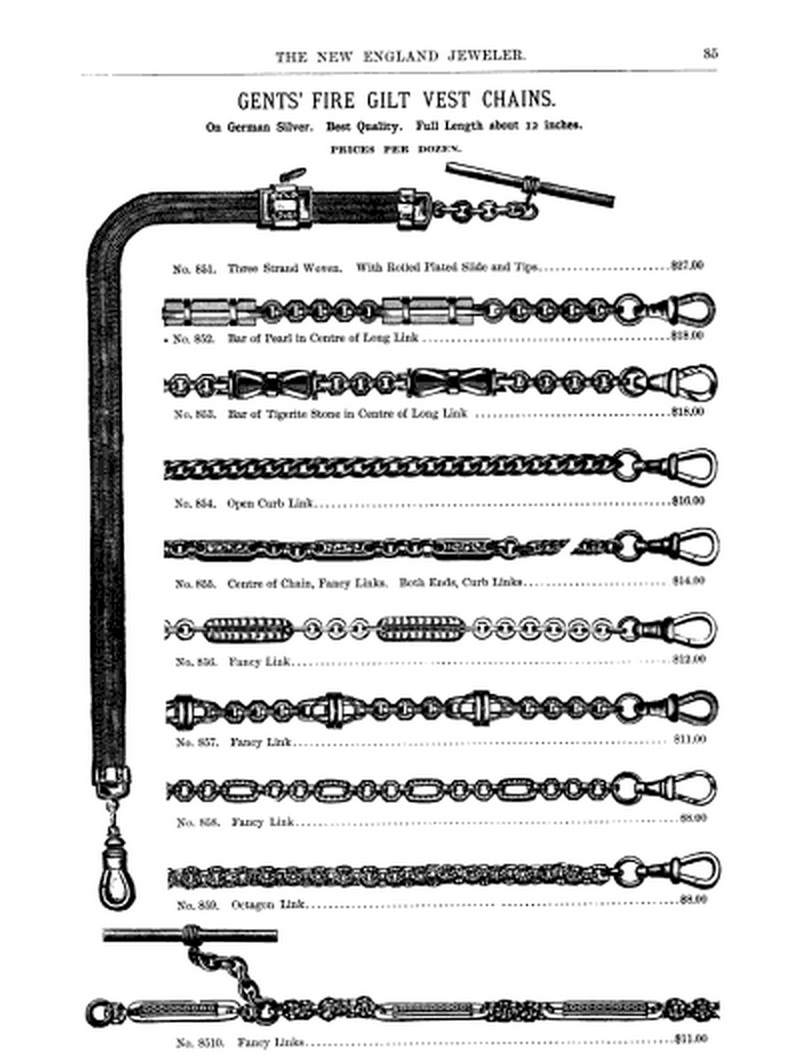

Items like these from the 19th century can easily be traced back to their catalogue. Charms and accessories on hair watch chains and necklaces are as bespoke to the piece as the hair itself. It is important for the collector to understand that these are the elements of daily fashion that a gentleman or lady (depending on the accessory) could adorn themselves with to remind them of their loved one. One element here to demystify is that they were used predominantly for mourning purposes and this couldn’t be further from the truth. As we have seen with hair as a material, this was fashionable and a way to show ones love and still keep that functional.

Catalogues are a great way of identifying chains and their accessories, as there are region-specific element that are reflected in designs, but for British and American chains, there was a great sharing of production. The Illustrated Jewelry Catalogue (1892) shows a range of chains and accessories in jet, silk, rolled plated, filled and silver chains, in the style of Victoria, Dickens, lady and gentlemen. The cost range here is $33.00 to $1.00, depending on style, length or material.

Just from the example from the 1790s to the depth and variety of the 1890s, the chain, watch and accessories had become necessary to fashion. Having the option to tailor visual presentation to the very nature of sentimentality in having a hair chain and a watch key with a hairwork insert devotes the gentleman to his family. As a Victorian ideal, this is perfect for the creation of what Victoria and Albert had established. Family stability was important to the growth of empires and governments, with people working together for the benefit of a Crown or office that could lead with the ideals of uniformity for promotion of the established family ideals. Mourning and sentimental fashion tied in well to this, as constant reminders of loved ones only made one work and define themselves harder in the public view for the benefit of a family.

Worn at the end of the chain, the key would likely have been requested by the wearer for its sentimentality and purpose. For such a small thing, the key relates directly to the public necessity for sentimentality in forms of design, as this is a key which could have been an oversight. It is a shame this this key is separated from its watch, as keys often were included within the same box as their counterparts, however, having something so important as a sentimental keepsake tells a tale of a time when every factor of the Romantic period was integrated within the elements of daily life.