A Mourning Tour: Charles II Locket

Memorial jewels that commemorate an event or a specific cultural moment in time have existed since antiquity and continue to exist as long as there is a developed society that can share the event publicly.

These are the jewels which indicate periods of loss or victory, marking events that can be looked towards as the catalysts for change which resonate through the daily lives of the society which wore these jewels. In this Charles II locket, we see a combination of two hearts and a rose symbol to the reverse. The locket itself is important for its time in many respects. This is a society which had survived the English Civil War, a war which not only destabilised the Monarchy, but led to internal religious challenge through the rise and fall of the Puritans within the Church of England.

Charles II

Charles II’s reign is marked as the period of Restoration of the English Monarchy. Following on from the wars of the Three Kingdoms between 1649 and 1651, leading to the defeat of his father Charles I (executed in 1649) during the English Civil War and the establishment of Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate, Charles II affirmed stability back into English society. The fallout from this was a society challenged by variation in religious opinion, confronted by unstable monarchical rule. Along with this, the world had opened up through new technologies and colonisation.

Richard Cromwell, Oliver Cromwell’s third son, succeeded him and led to the fall of the Protectorate (a period where the body of power over the British Isles was controlled by a Lord Protector), as his methods to open the Protectorate beyond the rule of army into acceptance by the populace led to challenging debate of Cromwell’s rule.

Without control of the parliament or army, Richard’s rule was overcome by the Rump Parliament, as established through a “Committee of Safety” that displaced the Protector’s Council of State. This was then replaced by a new Council of State in May 1659. It was a dissolution of power for Richard and led to the Monarchy’s restoration in 1660.

The restoration of the monarchy began in 1658, following the death of Oliver Cromwell and the decline of the English Interregnum. In 1660, Charles II began many reforms (and revisions of history stating that he had succeeded his father from 1649). Most importantly to memorial jewellery and the culture of mourning was the Clarendon Code, which in a series of Acts (Corporation, Uniformity, Conventicle and Five Mile), effectively re-establishing the Church of England.

Several events during the reign of Charles II led to the jewels of mourning and affection that dominated through to the 19th century. These being a combination of the Great Plague of London in 1665, with a mortality rate of an estimated 100,000 people, causing the king to flee London to Salisbury in July 1665. The Great Fire of London in September 2nd, 1666 was another such occurrence that, while not causing the high mortality rate of the plague, decimated London (13,200 houses, 87 churches) and left a lasting impression on a culture that had been challenged through political and religious thought.

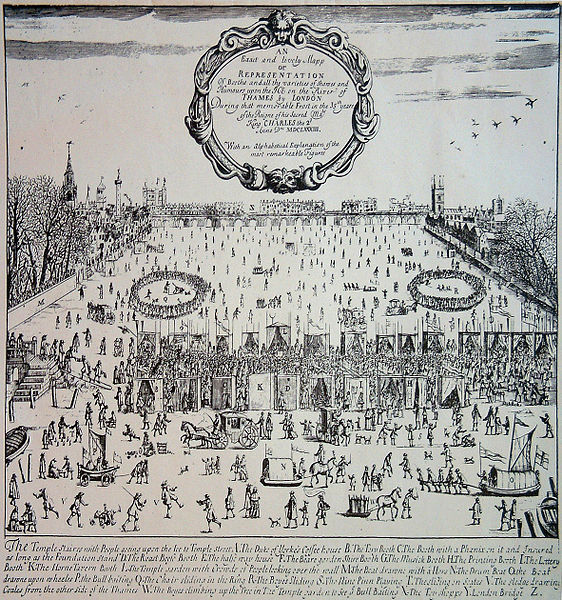

Combine with this a period of cold, during the “Little Ice Age”, where the River Thames frosted over. One such notable event was the Great Frost of 1683-84, with a two month frost that led to 11 inches of ice depth in London.

Connection between communities was advanced through the use of written language, particularly that within chapbooks. Chapbooks, pamphlets containing popular literature, were a popular source for many of the sentiments written in jewels, particularly inside posie rings. These cheap pamphlets grew in popularity, as they were sold cheaply (commonly a penny or halfpenny) and contained many popular ballads from the time. This pre-dates mass produced media of the early 19th century, when steam presses led to the rise of cheap newspapers. From the mid 16th century, these cheap and crudely produced booklets contained relevant popular content that varied from entertainment to political and religious content.

Society was at a point where events had overtaken the immediacy of global rule and communications that didn’t end at the limit of a village. Now, the world had opened up in ways which forced society to accept the relationships developed on a personal nature to be the truth, beyond religious or crown judgement.

Jewels for the Crown

Having a monarch that was representing God and the people was still an element of pride in a society amongst an ever-growing world. At a time when new lands were being discovered and colonised, the victories of a society were to be worn and shown as a cultural indicator of status. When a member of the crown was born, married or died, a jewel in their memory would be created.

In this jewel, we see the profile of the king, used quite like that of a coin. Immediately, this sets the locket apart from the typical pieces showing the frontal image of Charles II, such as below:

Many pieces with the king’s image don’t necessarily correlate with the exact time of the rule, with the image being painted a generation later for study or for commemoration, which is why this locket is so interesting. The detail isn’t as outlined for it to be a character study, but immaturely stamped and etched into the metal.

Upon the reverse is the Rose of England, the national flower, introduced as the Tudor rose by Henry VII (representing the House of Lancaster, a red rose, the House of York, a white rose), also stamped into the metal.

Charles II’s coronation as King of Scotland was 1651, as he was seen as the best hope of restoration, but wasn’t crowned King of Ireland and England until the 23rd of April 1661. This locket may have been formed as a souvenir/token for the coronation, given that the locket was in heavy usage by Royalists during the Civil War as a way of wearing a hidden dedication to the crown, it was a popular piece of jewellery for sentimentality.

Two Hearts

The dual heart motif is an unusual one, leading towards the assumption that the locket was made to commemorate Charles II’s marriage to Catherine of Braganza in 1662. Negotiations for this marriage began after the Restoration and the papers were signed on the 23rd of June 1661. Two ceremonies were held, a secret Catholic one and a public Anglican one at the chapel of Dormus Dei in Portsmouth, Hampshire.

Otherwise, the two hearts may lean towards the Royalist nature of the locket, being a union of the person and the crown, which establishes a loyalty to the crown.

Incidentally, it was the heart as a symbol which had become the personal means of representing love in jewellery symbolism, a symbol that still resonates today.

Locket and Construction

Using a material other than gold indicates that the jewel is one of a token or personal nature. The quality of the piece suggests that this was intrinsic to the wearer, or replicated for a small community to commemorate the crown in whatever fashion it may have been created for.

Higher-end jewels of the time utilised gold, crystal, enamel and gems to convey their status, making their wearing something which was part of social fashion. Lockets differ in that they were often worn under the clothes, rather than presented outside. A ribbon slide, common in the latter 18th century and worn at the neck or wrist, were more popular for denoting morning, sentimental affection and relationships, having everything from hairwork to gold wire cyphers and symbols being placed under faceted crystal.

This locket is unassuming. Its hand-etched “CR” is obviously done without the skill of the pressed profile of the king. Even the sides don’t match together at the base of the heart motifs. As can be seen from the interior stamp of the reverse, there is not equal symmetry to the design. This may be an affliction of age. Having the locket last so long and be damaged over time and wear would account for the metal inconsistencies, but not the design. The stamping and etching of the design was made for a purpose, but what we can understand through this is that it was singularly for the purpose of piety towards the crown.

Capturing the Sentiment

This locket may have held a token of love, an item of remembrance or a memory indicator for its specific time. There is no precedent for what it may have held, apart from the sentimental dedication to the crown, which it displays in a proud and profound way. Tokens for the crown exist today in jewellery, with all forms of miscellany made to denote a wedding, birth or death, however, this locket comes at the earliest time for continuity into the jewels we still produce today.