American Mourning & Sentimental Jewelry From the 19th Century

Perspectives and perceptions of sentimentality and mourning in popular thought and culture are cemented within the second half of the 19th century. What we consider today to be the ‘morbid’ trappings of death in the Victorian era were part of popular fashion and social custom. It is due to two major reasons that this period was so profound in its reach. One reason is the death of Albert, Prince Consort to Queen Victoria in 1861, which effectively locked mourning into popular fashion, as the monarch threw herself into perpetual mourning. As the crown had previously been the catalyst of style and changing fashion, Queen Victoria’s self-imposed mourning remained static, resonating throughout British society.

The other catalyst for popular mourning was the American Civil War. This event came at a time when all the methods of capturing memory had reached an apex. Photography rapidly developed as an affordable and faster process from capture to delivery since 1840, and as the Civil War lasted from 1861 to 1865; a time where the technology could capture the image of a loved one and the very horrors of the war itself. An estimated 3% of the American population were casualties during this time, one million and thirty thousand people of both soldiers and civilians. This is an incredible scale of mortality for a still young country to witness, a culture that burned with a fierce nationalism and identity. This nationalism even bleeds through to the jewels of the time, with the American Eagle appearing in black enamel on mourning jewels of the period.

Such a high rate of attrition led to the popularity and high production of mourning jewels. Sentimentality through the act of capturing the memory of a loved one inside a keepsake was attainable at a cost that had not been seen in early-modern history. Lower production costs, base metals and machinery had been perfected since the late 18th century in order to make a style of jewel that could adapt rapidly to fashion or technology. Styles of jewels became larger in the 1850s, due to the voluminous styles of dresses that were popular at the time. The crinoline required larger jewels to balance the wider skirts that were popular. Having photography in a jewel was a perfect way to balance the sentimental message with fashion. Worn at the neck or wrist, the photograph of a loved one was not uncommon and quite fashionable, set within a larger locket or brooch.

Methods of capturing a loved one weren’t relegated to the living. The Civil War allowed for a keepsake of a soldier going off to war to be taken quickly and given to the loved one. However, capturing the scenario of a post-battle area leads into the inevitable photograph of the deceased. This wasn’t the first use of the camera to capture death, with the practice being as important to sentimentality as had previous miniatures. The precedent for post-mortem photography verges on the ancient, with funeral and post-mortem imagery linked to early cultural developed. For the modern era, there was a renewed interest in deathbed paintings in the 1620s and 30s, with mourning as a social signifier entering the modern psyche. Post-mortem photography, however, began as quickly as the technology was adapted. In the United States, families were also changing from the community aspect to the smaller, family unit. During the 18th century, these Puritan communities would feel the loss of a single person as a loss to the community, whereas this had been restricted to the immediate family in the 19th century. Due to this and the greater freedom of the daguerreotype process in the United States (due to lack of patent control), post-mortem photography was widely prolific, more so than in Europe.

Early photographs were crude and the subjects were often not prepared correctly, but in a short period of time, the process was refined to studios and travelling photographers. As the style developed, the subjects became positioned and personal items of the deceased (or symbols of love) were placed around the body. Children are often the primary focus of post-mortem photographs and a great effort was made to make the subject look alive. For the photographer, making the subject look ‘asleep’ was one of the easier methods to do this, though studios specialised in ways to prepare the body for photography. These may be retainers to hold the bodies in position, massage to the limbs, rouging of the cheeks, ‘affixing the mouth closed with a forked stick placed under the chin and against the breastbone, closing the eyes with coins, and preserving the features by placing ice under the body.’ Different concepts were used in this method, but the primary focus was the same; to hold on to the memory.

“…parents evidently desired to represent their dead children in all kinds of attitudes in order to express their intense grief and their passionate desire to make their children survive in memory and in art, to exalt the children’s innocence, charm, and beauty.” Phillipe Ariès

As print became affordable and accessible, items such as the Carte de visite and cabinet card were available with variations upon the post-mortem photograph. ‘Madonna’ images of the mother holding the deceased child, couples holding photographs of the deceased and more public cards showing the body of a famous person are all variations on the post-mortem photograph. One of the more interesting is the pre-mortem photograph, with the subject shown before death. This was an admittance of the mortality of the terminally ill by the family and these images are not prolific in the same way as their post-mortem counterparts. As soon as photography could be adopted as a viable means for mass print and accommodate customisation, memorial ephemera adopted the technology quickly. These often were images of the person in life, rather than in death, but the industry was large enough to adapt the photograph technology for different memorial purposes. Beginning in the 1860s, mourning (or funeral) cards are still used with personalised imagery today.

By the 1890s, post-mortem photography (as well as the mourning industry in general) was on the decline. Symbolism, such as the coffin, had replaced the body as the symbol of death and societies were distancing themselves from the image of death. Mortality rates were changing and the fact of death was evolving. Now, photographs were more inclined to show funeral arrangements or even the funeral itself. Perhaps the more melancholy imagery was that of the child’s empty shoes next to a memorial (though this was used during the height of post-mortem imagery as well). Post-mortem photography was kept until the early 20th century, yet more common were photographs of the deceased (while alive) used in memorials. The practice itself is a direct reflection of the family and incredibly personal to the family unit. Unlike jewellery or adhering to any form of mourning fashion to publicise the effect of mourning, the photograph held the memory of the person and should be seen as a powerful symbol of affection.

Technologies and fashion have always been linked. Humanity adapts to its technologies, while sustaining common behaviour. In the same way that timepieces evolved to the watch and telephones evolved to the smartphone and even integrating technologies with the body, the ability to adorn oneself with anything leads it to have a hierarchy of fashion. If it is displayed in public, it has a level of personal worth. Mourning and sentimental jewels are no different. From photography, to the very materials used in their construction.

Mary Todd Lincoln is one such cultural identifier who represents a certain age. Her husband, Abraham, died on the 15th of April, 1865, after being shot by John Wilkes Booth. Combined with the outcome of the Civil War, public displays of mourning were now commonplace and fashionable. It is how fashion adapts to this ubiquitous mourning that is interesting. In this watch, there is the use of onyx, a fashionable mourning material, predominantly in French mourning jewels, that she wore at her lapel.

This watch has all the elements of being popular for its mourning style. The grand ‘empire’ design is carried through from the dominating lapel pin and its high arches, through to the thick border and clean circular shape of the watch itself promote a grandeur in its simplicity. It is devoid of the Gothic Revival flourishes (which borrowed heavily from the Baroque) and shows modesty in its simplicity. American mourning jewels are quite interesting. They are a mix of European styles, utilising what popular fashion was producing from France or Britain, relegated to either the most basic catalogues that had imported styles from England, right through to the culturally Catholic-influenced styles of the European continent.

In the above brooch, dating from c.1869, the style reflects the classical sensibilities from the 1820s. Being a popular housing for interwoven hair, the style needn’t change and its lifespan greatly exceeded its fashion. Simple jewels that don’t have clear markings of their style could adapt, much in the same way that mourning lockets from the 19th century are still in use today. Their meaning is contemporary at all times, as culture identifies with it. Particularly for American jewels which shared so many different influences, this isn’t difficult to establish in such a multicultural society.

On the 19th of April, 1865, Lincoln’s memorial service welcomed an estimated twenty five million mourners in Washington and around the United States. His body lay in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, travelling to Springfield on a largely publicised funeral train (his was the same route he took to Washington in 1861). His body was displayed in memorial services for public viewings, with the train holding three hundred guests and also the body of Willie Lincoln. In the New York funeral procession, an estimated one hundred and twenty thousand people were in attendance.

Based on this scale of public mourning and grief, the mourning scarf pin worn by Mary Todd Lincoln is an interesting look into public perception. Surrounded by the laurel wreath, the iconic Abraham Lincoln is idealised in a classical manner, showing a clear connection to the Greco-Roman period and popular Neoclassical period style. The Neoclassical period was in decline since the 1820s, which is a long stretch of time for any fashion to be at its height. From c.1760, the Neoclassical period influenced culture with a new perspective on identity and the ‘self’, utilising science and learning from the Enlightenment to connect to the classical world. Archaeological discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii influenced this, bleeding through to fashion and text. American identity connects itself back to this ancient period through iconography and design, seen in even the structure of government building architecture. It is a sign of respect and aspiration that the style is used within the context of the deceased.

Of course, mourning has been identified with the wearing of the hair of a loved one, however, it was predominantly a sentimental message that wearing hair jewellery conveyed. In these earrings, the three-tiered drop of the woven acorns and the above central weave were one of the most popular motifs in latter Victorian jewellery, for the very reason of their symbolism as being a statement of longevity, victory, new growth/life and power. It is a lovingly prominent statement of identity, but not one which is in any way negative. A nice symbolic way of being a positive statement.

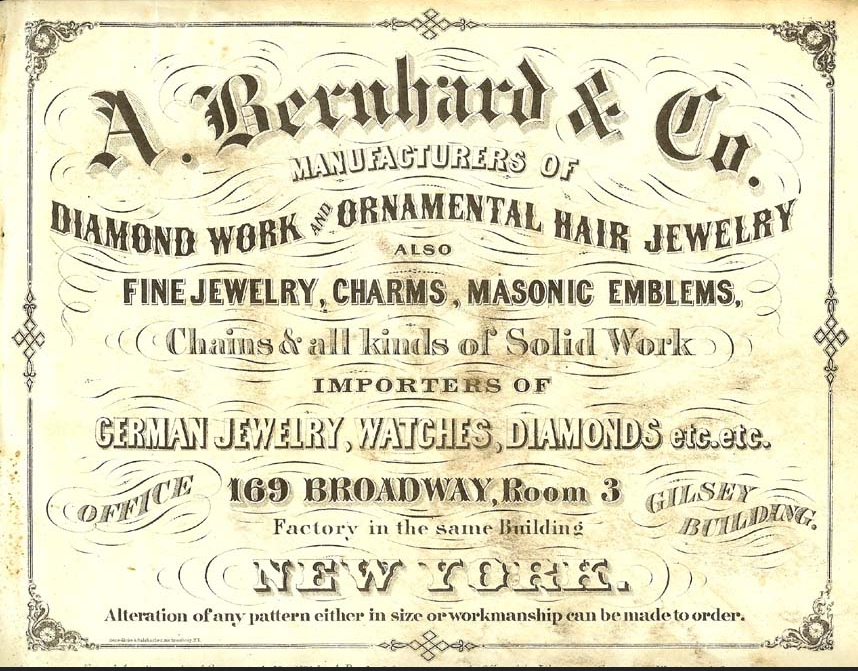

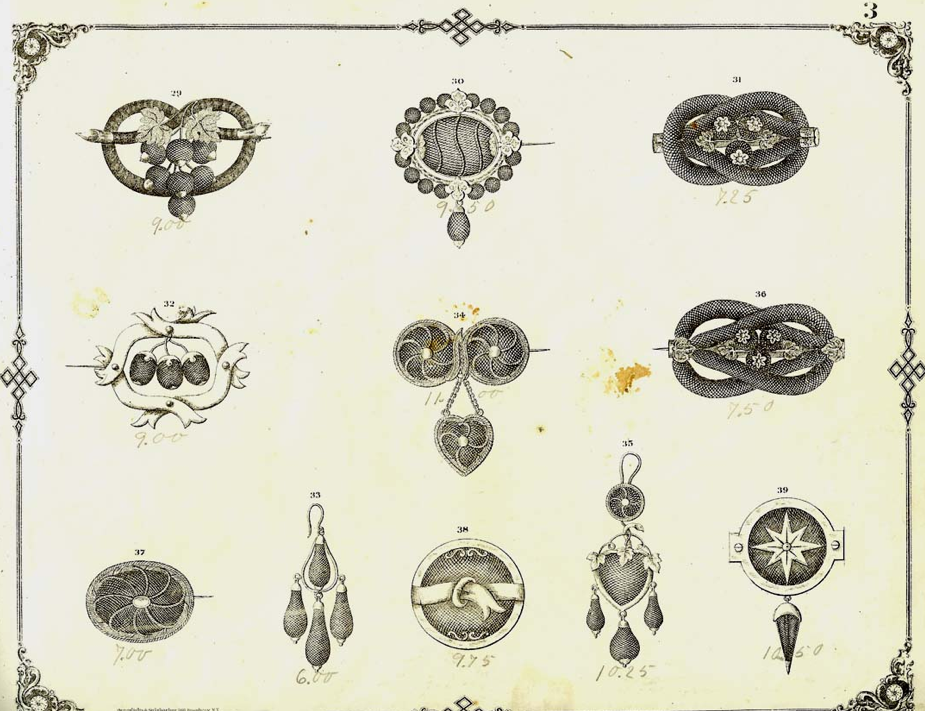

As these earrings are currently held in America, their origin may quite likely be with A. Bernhard & Co. As stated, they were ‘manufacturers of diamond work and ornamental hair jewellery / also fine jewelry, charms, masonic emblems’, clearly purveyors of all kinds of jewels, from expensive to otherwise. Hair was a material of low cost, simple construction and high production. Most jewels were colour-matched and not the original hair that was given to the jeweller to weave, but this still held the same sentimentality for the wearer. Quite often in sets of brooch, earring and bracelet, hair was woven from Eastern Europe through to America. With such a material in high production, its yield created a vast breadth of similar styled jewels, working their way into daily accessories.

Going back to the nature of why American jewels are far more fluid in their scope than a country with a dominating church or value system, the ability to have pockets of culture that had their own mourning beliefs added variety. A mix of religions and integrated cultures doesn’t apply to a set period of indoctrinated mourning in the culture, whereas English and French systems are far more strict in fashion. Here, there is the very notion of grief and love being the reasons for wearing tokens of affection.

The very notion that a catalogue could produce such a variety of hairwork jewels speaks back to the culture that required them. Hair was a popular statement of love and identity. It did not need to be a statement of grief or excess of affection, but simply a loving statement within fashion. This related to the professional catalogue and the home itself. Hairwork could be done within the household, as Mark Campbell’s Art of Hair Working (1875 / above links) shows. Having something of a keepsake of a loved one to weave into fashion, even if it’s just a basic twist of hair in a locket is a basic way of keeping love close. Given that mobility was high in the latter 19th century through mass transit, hair and photography were at the height of popularity.

Jewellery speaks to the aspect of culture that needs to be identified. Having the trappings of fine taste is a matter of aesthetics, but sentimental and mourning jewels need to reflect something more. It’s through the notion of love that fashion can adapt and show the very identity of love in an image, which was worn. Technology only helps this, improving ways to capture moments between people and advance construction methods to produce higher numbers of sentimental tokens. The American Civil War saw a great number of deaths which required families to enter mourning, hence the jewels and tokens of the loved one perpetuate. Society needs to reflect upon its past in order to go forward, learning from its sacrifice. When a mourning jewel, or token of love, is displayed, it is a statement of not only personal identity, but cultural identity.