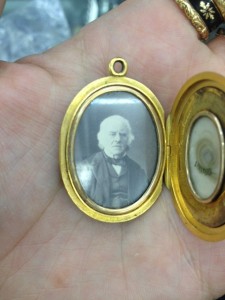

William Henry Smith Mourning Locket

Historical jewels are often marked by a certain quality that comes from having a notorious figure being memorialised. Be it from the amount of wealth that can be imbued within a jewel to create something that goes beyond the typical, to the efforts made by a family member to personalise the dedication of mourning for a loved one, historical jewellery was made for the announcement of mourning for a figure that would be recognised.

The origins of this locket for William Henry Smith (1792-1865) are as auspicious as the man himself. Smith continued on his parent’s news vendor in Little Grosvenor Street, London, growing it into the business which would become the company WHSmith, following the death of his mother in 1816, where the business was divided equally amongst the brothers.

Smith was the most capable of the brothers and grew the business to success, eventually adding his son as a partner (renaming the business W H Smith & Son) in 1846.

In so many ways, this locket reflects the change of the 19th century and the influence of new wealth which allowed for the trappings of mourning leaning more towards affectation above plain necessity. It tells of a tale of a man who had built his life and living standard through hard work, pushing through the barriers of society to become a respected businessman in his own right. The fact that the business runs today around the world is a testament to his hard work and dedication.

When we look back to the locket, we see a confluence of elements. There are certainly the more humble designs of typical Victorian jewellery motifs of the day, particularly in the star design which was a common element from the 1860s (and used widely through the Aesthetic Period to the Edwardian Era) to the Niello cross-hatched inlay of the black enamel to the surrounding pattern – a style popularised since the 1820s when machine-turning led to faster production of the pattern.

Upon the reverse, the initials, while decorative in their Grand Empire design, are not excessively designed outside of the Victorian style. What does make this beyond the typical is that the locket is enamelled on both front and back, whereas many pieces would have one design element and nothing on the reverse, as this would be worn either under or above clothes and not be seen.

Excessively designed hairwork can often lead to the suggestion that the hair used was not that of the loved one, but that of colour-matched hair by a jeweller. 19th century hairworking artists found it cheaper to purchase hair from convents on the Continent rather than use the hair given to them by clients, as stated by Godey’s A Series of Papers on The Hair (1855):

“Among the many curious occupations of the metropolis of London, is that of the human hair merchant. Of these there are several, and they import between them more than fifty tons of hair annually. Both England and the United States draw a large portion of their supply of human hair, and of articles made of hair, from France and Prussia. A singular feature on the continent is this ‘hair harvest’, as it has been termed”.

The 1840s – 1880s saw popularity in rings, bracelets, earrings and many other mass produced hairwork jewellery items. However popularity in English hairwork declined after 1880s, as did the mourning culture. New art styles, changing fashion and jewellery construction had evolved, making hairwork seem outdated in comparison.

In Smith’s locket, the hair is unassumingly twisted and tied with gold wire, linking this to be quite certainly Smith’s hair. The balance of the hair within the glass oval compartment isn’t placed in any way that would show the piece was designed around the hair, but simply placed inside. Showing the material backing seems like a poor utilisation of the locket’s design, which further enforces the theory. An assumption could be made that the locket was pre-designed and customised for Smith, however with the bespoke initials upon the back, this seems less likely.

Originating from 1865, the impact of photography during this time in mourning jewellery was exponential. Since the Daguerreotype in 1839, the development of invention in photography through the ambrotype, tintype to the cabinet card had a resonant affect on sentimental jewellery, with the difference in shape and size for jewels accommodating the development of photographic styles. From a mourning perspective, this led to the instant capturing of the loved one, rather than the expensive and time consuming miniature portrait that had proceeded it. With the development of the technologies, the cost became cheaper. The daguerreotype was an estimated five dollars (US) per image, which roughly translates to a regular week’s pay at the time, while the ambrotype at approximately twenty-five cents, while the tintype was sold for a penny or less. Technological development of these processes led to faster capturing of the image, with lighter cameras allowing for greater mobility. Having an image of a loved one was not so much of a privilege, but an expectation of the family. In the Smith locket the image has been captured and placed within the locket itself, with the size of the locket accommodating a standardised dimension for the image.

Many developments in the 1860s created the basis for the development of industry that exists today, indeed, many of the major events defined the existing mourning industry. Between 1840 and 1860, the Victorian Era had established the ideal Christian Family, which reflected back upon the values of the pre-Enlightenment Era. This Gothic Revival period produced simpler, yet dominant designs in jewellery which removed the Neoclassical pomp that took the focus of mourning away from the religious judgement upon death and put it upon the individual, displayed in literal depictions of the person in mourning or allegorical classical scenarios.

But by the 1860s, the Victorian Era hit upon a new catalyst for mourning style. The death of Prince Albert in 1861 led to Queen Victoria’s perpetual mourning, which allowed for people who were hungry for new stylistic influences to approach other cultures and put money towards artists for new aesthetic creations. Previously, the aristocracy had been the driving force for style and change, yet with a Queen in mourning, this wasn’t what it had been during the Georgian reign, where money was heavily invested into the arts and culture.

In the 1820s, many influences upon society offered greater cultural flexibility within the social structure. The excesses of George IV and his investment in the arts bought new influences into the United Kingdom. From the death of Princess Charlotte who died in 1817, mortality was absorbed as a cross-cultural, kingdom-wide event, imposing values of the affectations of mourning on people which would resonate for the remaining 19th century. The values that were appropriated to show this in fashion led to the Gothic Revival being the identifier for grief and virtue, due to its return to religious values and simplicity that takes that pomp away from the fact of death.

Following into Queen Victoria’s early reign, it was innovation led by Albert, Prince Consort who helped impose many of the Victorian standard values upon society. The Great Exhibition of 1851 came about during a time of European and Latin American economic turmoil in 1848, leading to revolutions following the rise of nationalism. Albert’s dedication towards acknowledging the underprivileged and offering financial and educational assistance was an incredibly bold stance for the time, particularly when his family in Europe was being threatened. Since 1843, Albert was President of the Society of Arts, which, from its annual exhibition, became the basis for the Great Exhibition. Based in Hyde Park within The Crystal Palace, the value of science, art and industry became a matter of pride for British society, which is a progressive step and one that shows the great innovation of Albert, himself. As a counter to revolution, The Great Exhibition stood fast and as a catalyst for art and innovation, the impact upon jewellery design that was revealed through new techniques of metallurgy and style resonated back through society.

Smith was an entrepreneur, adapting to new technologies. With his mail-coach system, Smith had country-wide distribution, using the ‘first with the news’ tagline as a selling point. His son, William Henry II, took advantage of ‘Railway Mania’ speculation in the 1840s, seeing the interconnectivity of railways in Britain and exploiting this for newspaper circulation. Transit is one of the most important catalysts for change and development, particularly during the 19th century when many of the old world was opening up to new paths of communication. Suddenly, the impact of events in America, Europe or Asia/Pacific could be felt a lot more suddenly than ever before. The American Civil War, Suez Canal in 1869, the establishment of the London Fire Brigade and the foundation of the Salvation Army are all happenings of the 1860s and none of these would resonate so much without the infrastructure of the railroad transatlantic cables. Messages and people could be speed across vast distances at great pace.

Within the locket, the styles used by the Smith family in its creation are styles which would carry on through to the 1901. Through the ability to mass produce lockets of this style and have them customised, anywhere within the Western colonised world could access this style of jewellery, and thus the consistency in style over a prolonged period in the latter 19th century was complete. Mourning had its pre-determined styles and each of these was a necessity of mourning that needed to follow the rules of Court, or at least take the affectation of mourning for the proprietary of the family.

William Henry Smith’s legacy lives on through his business and the nature of having a place where people can buy books and share knowledge is a legacy of communications which has effectively changed the world around it. This locket is a beautiful piece that resonates the style of its times and also the times which would follow. The use of the photograph and the diamond show that the person who wore it loved the man intensely, and regardless of quality or era, that speaks loudly even today.

Further Reading:

> Photography in Jewellery Part 1

> Not Lost But Gone Before Locket

Courtesy: Pip Terry