Wellington Mourning Brooch

A state funeral has the highest cultural impact on mourning fashion. From the creation of memorial jewellery to the random souvenir accessories; this event unifies a country or an empire and has a resonance towards the funerals and the surrounding fashion that will happen in the future. Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington died on the 14th of September 1852 and his funeral on the 18th of November was a public outpouring of love and respect which produced pieces, such as the cameo of today’s article.

In the Doctrinal and Practical Reflections on the Funeral of Arthur, Duke of Wellington: A Sermon Preached in the Church of St. James, Curtain Road, Finsbury Square, London. 21st of November, 1852, a perfect encapulation of the funeral was written;

“What though the Duke fairly earned and received more honours and rewards during his life – had a more magnificent funeral when he died – and shall have a more sumptuous memorial to commemorate his fame – than any other hero of this or any country?”

The people who are being mourned have offered their services to the Crown in a way that has often not only defined a certain aspect of it, but may have very well protected it. In the case of the Duke of Wellington, his accolades as the figurehead who protected Great Britain against Napoleon, particularly with the strategic victory of the Battle of Waterloo, deserved a funeral which could dignify his achievements.

In the same way that Princess Charlotte had a public outpouring over her death during a miscarriage on the 5th of November, 1817, Wellington’s funeral was had enough of a cultural impact to create a series of mourning souvenirs that would resonate and continuously be produced throughout the 19th century.

The Iron Duke

Arthur Wellesley was born in the Kingdom of Ireland on the 1st of May, 1769. Known best for his military career – he was first commissioned in the British Army in 1787 – he had a successful political career. Following his victories in the Napoleonic Wars, he was ambassador to France and given a dukedom for his efforts, after the exile of Napoleon. Joining with the Prussians during the Hundred Days, the Duke defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo and then went on to twice become a Tory Prime Minister, first in 1828.

His incredible success in the military and in politics constantly made him a public figure and holding a position of power, which can be seen through his appointments as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army.

In order to identify with this brooch, a look to the Duke’s funeral procession is required. It is within the procession itself that the identification with memorial objects, and the nature of how his death created such a large impact upon British culture can be discovered. Harry Garlick’s The Final Curtain: State Funerals and the Theatre of Power shows a good representation of the funeral procession and its relevant symbolism:

“The Duke of Wellington’s funeral procession on 18 November 1852 , from Horse Guards to St Paul’s Cathedral, was for him a literal journey’s end. But it also marked the coming together of a number of aspects about the mythological life of a people – a journey produced and stage-managed by the ruling class for political motives, using familiar objects symbolically as basic elements of ritual. While, for instance, there were funerary symbols now familiar to us such as the horse with a pair of backward-facing Wellington boots, the dominant symbol of this funeral was the Duke of Wellington’s funeral car which functioned both as a hearse and symbol of that great Victorian icon of democracy, the railway. Much of the focus here is on the iconography of the Duke’s funeral car and on the ritualistic implications of that iconography.

One of the more important aspects here is the symbolism within the Wellington boots and the car itself. The industrial construction of the car shows the nod towards the railroad, with the large wheels and carriage design. On top is the casket and cover, with grand opulence in black and gold trim. With the large procession and crowds flanking the procession, it is within moments like these that imprint within a society and lead a cultural movement which resonates beyond the personality of the deceased. Indeed, within the sermon of the Doctrinal and Practical Reflections on the Funeral of Arthur, Duke of Wellington, a contemporary look at the funeral establishes the feeling of the time:

“And a grateful people have done the Duke of Wellington honour in his death by a public funeral, and a general mourning. To my mind, by the very solemn and edifying manner in which last Thursday was observed in the metropolis , and all over England, the tolling of the church bells, the closed shops, the religious services, the subdued and decorous aspect of the populace, the inhabitants of England and its metropolis, did Wellington more honour in his death than was done him in the splendid pageantry of his public funeral. Last Thursday will be a day to remember and record. Not that I would in any way depreciate the grand national demonstration made at his interment.”

Humanly speaking, Wellington fairly earned all that his country showered upon him while living, and all that has been manifested upon his death and burial. No; I would not grudge even the lavish expenditure at his funeral. There was a moral in the performance; solemn lessons such as these were taught by it; – “It is appointed unto men once to die.” “Man that is born of a woman hath by a short time to live.” “In the midst of life we are in death.” “We brought nothing into this world, and it is certain we can carry nothing out.”

“What though the Duke fairly earned and received more honours and rewards during his life – had a more magnificent funeral when he died – and shall have a more sumptuous memorial to commemorate his fame – than any other hero of this or any country?”

There is almost a justification for the funeral being so opulent. Under the eyes of the Christian God, these kinds of trapping would be reserved for royalty or the clergy, yet these were given to someone who had given great service towards the country. In that the funeral was so overly decorative, the account justifies the opulence through devotion and service, while stating that Wellington was a humble man and one who did not appreciate vanity.

Jet and Glass

The contemporary ride of the jet industry, which aligns to Wellington’s funeral, was one that resonated through the mourning industry, but was also a material used for the purposes of fashion. It was popular enough to spawn several imitations which could be produced through cheaper materials and higher yield, while still retaining the similar style of jet itself. In this brooch, we have a pressed black glass cameo in a gilt frame. A humble collection of materials which could be produced in the high numbers required for a public period of mourning.

Despite the lack of a large jet industry in Whitby post-Roman times, jet was known and referenced during the 18th century, but products tended to be mostly crude.

Muller argues that the transition from lighter Regency-era dresses to the heavier crinolines and larger styles of the 1850s and 1860s required larger jewellery to work with them, hence jet’s lightweight appeal and larger size provided to perfect accompaniment. Jet was presented to the public at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and its popularity grew exponentially, facing almost immediate Royal patronage from France, Bavaria and of course, England. Thomas Andrews was the ‘jet ornament manufacturer to HM the Queen’ from 1850, and this would be a most prodigious position to hold, as upon Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria only allowed jet jewellery to be worn at court. Society followed on from court etiquette and mourning fashion and culture swiftly became part of mainstream culture.

By the 1870s, the annual turnover of the Whitby jet industry was said to be over one hundred thousand pounds, with a jet craftsperson earning between three and four pounds a week. From 1832, there were only two shops employing twenty-five people to 1872, where two hundred shops employing fifteen hundred women, men and children, taking over the landscape of Whitby. Development of machinery, such as the lathe, also helped to facilitate the growth of jet production meeting the high public demand for jet pieces. However, demand was so high that soft jet was imported from Spain and France, mainly for beading (as previously mentioned, soft jet tended to crack and many surviving pieces reflect this today), giving the jet trade what was considered to be a ‘bad name’, hence the attempt in 1890 to trademark ‘Whitby’ as a quality of jet. Jet was also seeing great competition in lesser-quality imitations which were far cheaper and by 1936, only five craftsmen were left. By 1958, the last Victorian trained jet carver had passed on.

But was it just the competition of imitation jet that started its decline? The entire mourning industry was in a decline from the mid 1880s – an entire generation of a culture with once fluid fashion changes had been living under the shadow of mainstream mourning culture from 1861, due mostly to a queen perpetually in mourning. By 1887, for Victoria’s golden jubilee, she had started to lessen the mourning restrictions and re-emerge in public, but there was even a cultural shift that had begun with women who lived as the centre of household mourning starting to rebel against the older ways. Style had remained largely consistent with little movement since the 1860s, though women’s clothing had lost the heavier crinolines, bold mourning jewels remained bold and prominent. This female paradigm shift had started to become an outward rebellion, with some women even wearing their veils backwards as an act of defiance. The Art Nouveau movement emerged as a breath of fresh air, with its opulent, organic, styles, using nature as its dominant motif, rather than retroactively mining the past for revival styles. Jet was not conducive to this new art movement and did not adapt. Black stones used as a material following this period in Art Deco were often onyx or glass, which became, and remains, popular to this day.

As far as jet imitations go, French jet is one of the most common. For a collector, it’s hard to discern directly a piece of French jet, not because it’s to be confused with real jet in any way, but simply because many of the designs were so innocuous that finding a 19th century piece of French jet and identifying it from a piece of black glass used all the way through to the 1940s can be difficult. When French jet designs are used in more period styles, such as hat pins or showing more typical bold 19th century designs, then it’s much simpler, but there is an absolute abundance of French jet on the market that have been torn from buttons, trimming and various ancillary accessories.

English variations of French jet are called Vauxhall glass and you can often spot a piece of either French jet or Vauxhall glass from its cold touch, high reflective surface (strangely enough, like glass) and it will have a touch of red when held on some angles towards the light.

Quite often found in the trim to mourning dresses (particularly in the second and third stages due to its reflective surface and light weight), French jet was heavily produced and very cheap.

Souvenirs and Memorial Jewels

A brooch like this signifies more about its relevance in Great British culture, more than just to identify with the man himself. This is a symbol worn with pride upon a person to unify them with their culture and their surrounding citizens, a piece which transcends the status of personal mourning and makes it into a uniformed mourning of an entire culture.

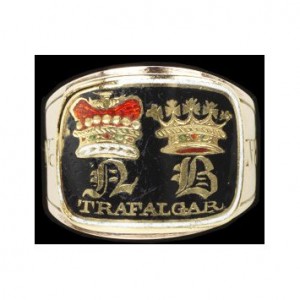

Pieces like this were reproduced, much in the same way that Lord Nelson’s mourning ring still had commemorative editions. The victories that these cultural personalities faced represent a culture, more than the actual event itself. For as long as there will be a Great Britain, these symbols are its identity, solidarity and strength.

While this is just one brooch in an entire plethora of objects made to memorialise the Duke, Harry Garlick’s The Final Curtain: State Funerals and the Theatre of Power looks towards the representation of the Duke as a visual symbol that could be identified with in memorial objects:

“The use of woodcuts, lithographs and sketches capable of mass reproduction was widespread and growing at the time of the Duke’s death. He was even represented visually in three dimensions; there are, for example, on show at Walmer Castle, his residence as Lord Wardon of the Cinque Ports from 1829, a number of shelves of statuettes of the Duke. One of the ways in which the Duke was represented was as a Toby jug, which virtually sealed his status as a folk hero. There is an interested aesthetic comparison to be made of the folk status of the Duke as a Toby jug with more heroic representations after he had just won Waterloo. The Toby jug, while still recognisably the Duke, displays his features softened and rounded, yet moving towards caricature, domesticating the hero of Waterloo into a totem completely at home in many households of all classes. Also, just three days before the Duke died, there is mention in the Illustrated London News of a new statuette by Alfred crow quill.”

Which brings back the representation of the Duke’s profile. While he had been captured in image during his older years, this piece shows him in the classical ideal, from the style of the hair to the pronounced nose and jaw. His strength is timeless and makes wearing this brooch reflect the person who had worn it as a symbol of strength and one that shows strength for the empire. The profile isn’t jovial or attainable, rather it is the ideal of the man whose strength is captured in a way that reflects Roman/Greek timelessness.

Further to this is the following reflection from Garlick upon the proliferation of memorial objects post death:

“Asa Briggs, in Victorian Things in a chapter significantly titled “Image of Fame”, reminds us that this was an age in which there was a proliferation of produced objects that commemorated people or events, which he sees as a sign of Britain’s growing industrial might. Briggs points out that “Stone or paper or wax were not the only materials used to register people and events. There were also objects in wood, metal, silks and glass.””

This glass brooch, along with its similar pieces, is a signifier of Britain’s industrial might. Indeed, when seen in context with the growing Jet industry and how glass replicated its style in fashion, the industry was built around the need for a specific fashion. Even the fact that within the country an industry of fifteen hundred people could develop rapidly was a testament to the rise of industry and that an affectation could drive such numbers.

Impact

Such a prominent statement of grief in public ties the wearer to their country; identifying with a person who had become a symbol for it. Many within Britain had much to be thankful for through the Duke of Wellington, as they had lived through the Napoleonic Wars as the protection that his military planning had afforded them, which makes the sentiment of the brooch even more person.

Still identifiable today, memorial jewels are timeless representations of their culture, with these symbols still in production.