Mourning Sampler for the Medcalf Family, 1857

Needlework is one of the most personal expressions of mourning art, and this is due to the lack of a mainstream industry surrounding it. Pieces were constructed in the home, making their sentiments genuine and heartfelt, unlike the established memorial cards whose biblical verses and poems were already chosen. Being an primary part of the education of young women, weaving and needlework are essential in the personal creation of mourning items, specifically samplers and their evolution. Indeed, it was in the final exams at Dame School where samplers were tested, often taking a year to create.

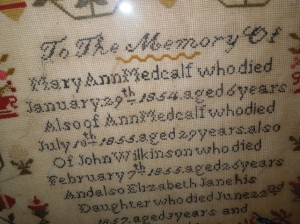

The sampler seen today holds a remarkable sentiment for four members of a family, cascading through 1853-1857. Mary Ann Medcalf (6), Ann Medcalf (29), John Wilkinson (26) and his daughter (3 years, 8 months) are captured within the fabric of this sampler by what could be assumed to be a family member as a reminder of their memory.

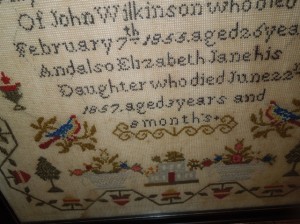

To The Memory Of

Mary Ann Medcalf who died

January 29th 1854 aged 6 years

Also of Ann Medcalf who died

July 10th 1855 aged 29 years also

Of John Wilkinson who died

February 7th 1853 aged 26 years

And also Elizabeth Jane his

Daughter who died June 22nd

1857 aged 3 years and

8 months

Many of the techniques had their origins in Europe (England and France) with quite advanced stitches. Metallic, silk and chenille’s are all common materials found within a piece of quality. As written by Olberding, US mourning samplers involve more crewel work than cross-stitch, with some of the stitches being tiny long-and-short and chain stitches that give the appearance of engraving. Some of the backgrounds were painted instead of stitched and many silks came from China and fibres from England or France.

As the base fabric, velvet, silk or linen were incorporated. Designs were then put onto the base fabric (often by an instructor) while the students would fill in the lines and choose colours and threads with guidance.

When looking for styles in construction of samplers, DeLorme describes these techniques; “the simple cross stitch, most commonly employed in a young girl’s first sampler, was later to include satin stitch, French knot, running and outline stitches, seed and bullion, couching and crewel.” Mourning samplers with water colour painting in the piece, as well as coloured silk, wool, or chenille thread on silk or satin background are also prolific, according to DeLorme.

America, from around the 1780s inherited much of the needlework technique being done in Europe, and as a largely puritan society, their samplers reflected much of the neoclassical symbolism of their time. American and European samplers still quite easy to source due to the practising of folk art. Much like the hairworking industries, needlework is area specific and different areas reflect different work. Something in regional Germany may display quite different techniques than an English piece of the same time. At its core, however, the prerogative of the stitching and content are at the creator’s whims. Often religious symbolism is displayed in samplers, and with death as the constant in mourning samplers, religious motifs are not unusual. They hold a powerful connection to the upbringing of a person within their household and the beliefs of a household and community, hence anything from the alphabet to heavy symbolism are employed.

Due to samplers being so personal, they don’t suffer from the standardisation of mainstream symbolism. They are they family concept of what a mourning symbol should be. If that is influenced by a secular belief, a family concept or an immediate social understanding, it appears in the design. There’s no choosing from catalogues or influence by an over aching style that is ushered in by a monarchy or popular figure. They are simply the family’s depiction of grief.

In the Medcalf sampler, the depiction of the final reward after death appears first, without the morbid affectations of symbolism that would commonly be seen in the 19th century. Gone are the symbols of desecration of the body and introduced are symbols of nature; from the birds to the floral elements, all culminating at the temple below; this sampler was made as a holistic memorial, not an immediate reaction to death. As a concept, this is quite like an album for its time, but rather than a collection of images, it is the creation of a household through every stitch.

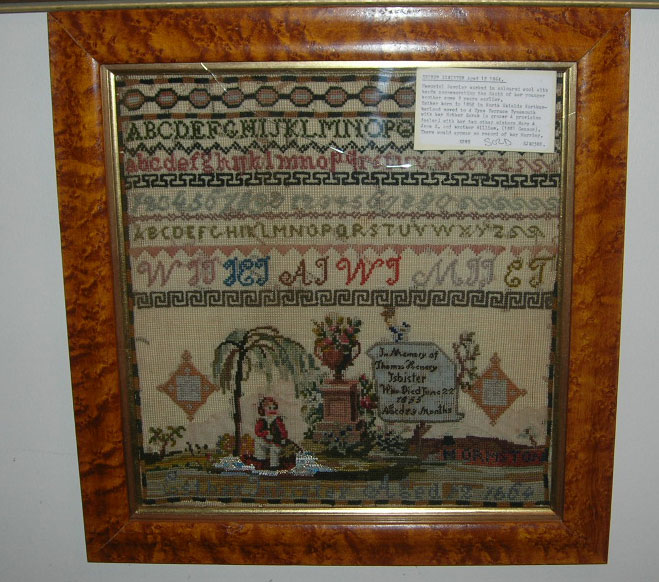

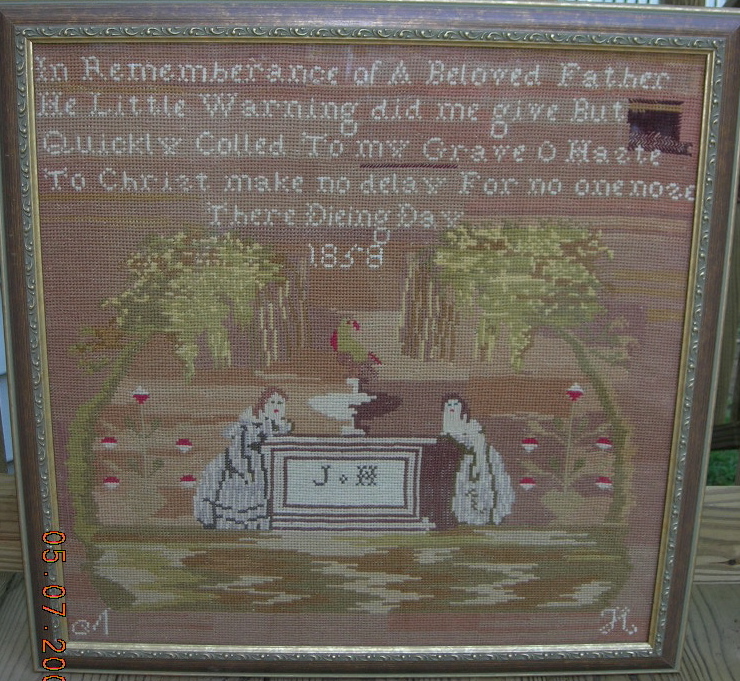

Compared to the sampler above, the Medcalf piece is far more individual. The piece above, while of excellent detail and quality in the stitches (notice the shading and the depth of the mourning depiction), it conforms to the Neoclassical paradigm of what mourning was. This is a leftover from the early 19th century, which would have these Neoclassical depictions of mourning utilised as the standard. This would likely have been a learned stitch through the family to acquire the skills, as this scenario became less and less common throughout the 19th century.

The Medcalf piece shares more common themes with the below sampler:

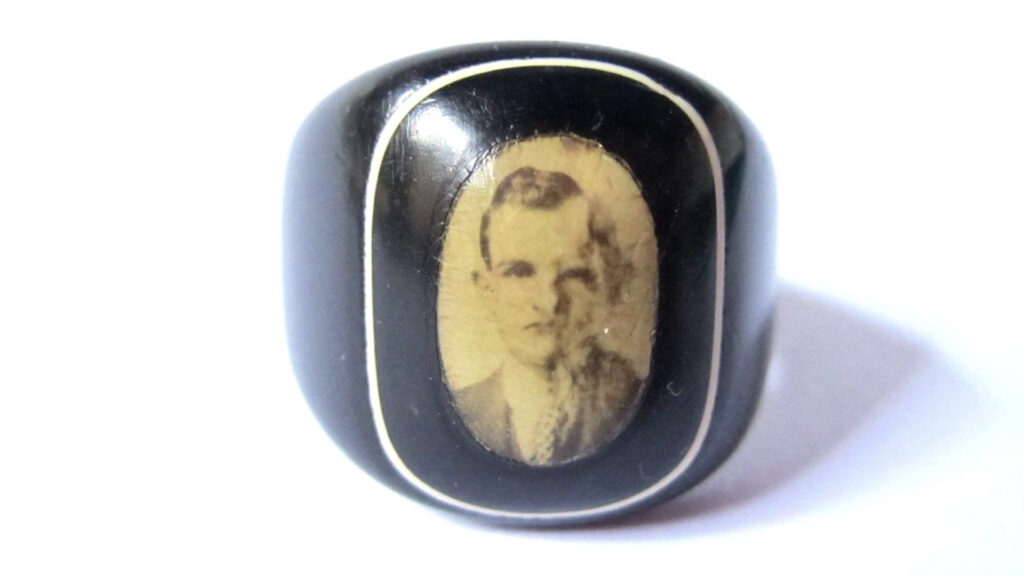

Showing square shapes in the stitches and even sharing the colour palette relates the two, however the mourning depiction here is directly related to one family member and shows the two women in grief. Samplers could act as an immediate way to capture a moment and a mood, much the same as a silhouette would be before the advent of photography. Be it in a literal depiction, such as the capturing of the person, as in the above image, or in the sentimental dedication of the writing, these are the moments that are held on to by the family and passed along. They were relatively cheap and required a homemaking skill which was passed down through generations, hence the ability to create a message of the family is a powerful thing at a time when high quality miniatures, photography and art required either technology or money to create a piece.

What is most sentimental about this sampler is how grand it is so capture so many elements of the family. From this, we can deduce the construction of the family, the level of skill that was in the family to produce something so elegant (notice the change in fonts, calligraphy and serif/sans serif) and even a suggestion as to the religious nature of the family without the overt Christian symbols that can be found in many pieces.

Capturing the memory of a person or family is the heart of mourning jewels and art. Without the threat of losing a memory or the concept of love, these things would not exist. The ability to remember and learn from a person, while carrying that memory on, is the most powerful signifier of human development. Appreciating every stitch in this sampler lets us remember these individuals and find out more about their time and moment.