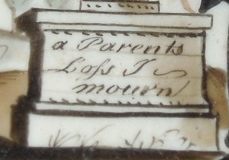

‘A Parents Loss’ Mourning Miniature

It is often when appreciating a mourning jewel that the nature of the subject gets lost. The beauty of a jewel, the artistry and the quality all define the appreciation, but the most grounding element is always in the dedication. With the dedication in this miniature, we see the personal statement of combined loss – ‘a Parents Loss I mourn’. The individuality of this miniature puts the mourning female in the actual depiction, as opposed to being drawn to a Neoclassical ideal. Much of this goes into the simplicity of the design, as the symbolic elements were popular at the time and often pre-defined in the miniature, then customised by the person who purchased it. Here, a basic competency in the design aligns with the post turn of the 19th century style; its design is simplistic and colourful, it has a larger, oval shape (while the navette shape is closer to the 1790 period and the various elements are drawn in a way that represents the standard of the time, but also is remarkably individual.

Turn of the 19th Century

Jewellery design in the 19th century correlates with the change in society through art. Much of the style in this particular piece owes its history to the 1790s and the dominance of the larger, allegorical depictions of Neoclassicism. Art was the representation of personal emotion; the female being the most dominant reflection of the ‘self’ in jewels. This female would often be an ideal classical representation, sitting or standing next to a memorial or sentimental symbol; most commonly a plinth with an urn on top. In the late 18th century, the influence of Greek and Roman art in fashion and design cannot be understated. The above the waist definition in female costume, as well as the lower cut was popular and it was seen in the classical female figures depicted within the jewels; be they rings, pendants, bracelet clasps or miniatures. Often painted on ivory or vellum, these Neoclassical depictions became the resonant representations of love that were displayed and worn in society.

As the 1800-20 period was particularly volatile in international politics. With Napoleon crowning himself Emperor of the French in 1804 and subsequent at defeat at Waterloo in 1815, to the establishment of the Austrian Empire and the growth of the United States through the Louisiana Purchase and annexing of the Western continent, the perspectives of society were only more fuelled by a liberalism that challenged traditional social structure. The thought which came from this would eventually spark stronger national belief, particularly in England, which had suffered through the madness of George III and the excesses of George IV. Military victory had given the nation solidarity, as well as the financial benefits of the Industrial Revolution created a society which was no longer insular.

Much of the 19th century’s change in thought was a reaction to religious non-conformity in an effort to swing back to the ideals of the High Church and Anglo-Catholic self-belief. This was a time when heavy industry was on the rise and modern society (as we consider it today) was established, a time of radical change that challenged pre-existing ideals of society. Though there had been growing small scale social mobility from the late 17th century, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the middle classes having the opportunity to promote through society with the accumulation of wealth. Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, a designer, architect and convert to Catholicism, saw this industrial revolution as a corruption of the ideal medieval society. Through this, he used Gothic architecture as a way to combat classicism and the industrialisation of society, with Gothic architecture reflecting proper Christian values. Ideologically, Neoclassicism was adopted by liberalism; this reflecting the self, the pursuit of knowledge and the freedom of the monotheistic ecclesiastical system that had controlled Western society throughout the medieval period. Consider that Neoclassicism influenced thought during the same period as the American and French revolutions and it isn’t hard to see the parallels. The Gothic Revival would, in effect, push society into the paradigm of monarchy and conservatism, which would dominate heavily throughout the 19th century and establish many of the values that are still imbued within society today.

Detail

Let’s look to the individual elements of this piece. On the reverse, we have the combined initials of the departed, as well as the combined hair weave. This is a typical style for its time, having much influence from the French sentimental jewels of the first quarter of the 19th century.

As you can see in the above, this miniature shares a commonality in the design of the monogram and the hair. The relationship of these elements had their history in the 17th century, with hairwork often being underneath the gold wire cypher, but now it was standardised and embellished. The 1780s saw a return of this style and a prototype for this piece, with a prominence taken during the 1790s:

Having foil and/or blue cobalt glass is a typical element to find in the reverse of these miniatures, with the French influence in colour connotation also playing at part Blue, denoting the loved one to be ‘like, or considered royalty’, was a way of expressing love.

Otherwise, the front of the piece shows the classical symbols of the urn, female, plinth, cypress and the border of the willow. The willow is one of the most important features in Neoclassical jewels, being a feature that would be shown in the foreground and border the scene. With the willow overhanging the north of the piece, we can see the simple dashes of the leaves in darker brown, over the top of the lighter wash. Note the base colour of the blue sky underneath and how that morphs into the white of the scene, as if the colour is being drained from the scene in the sadness of the female’s grief. This is eventuated by the brown earth, a sign of mortality, and its sparse tufts of grass (which lack colour).

Female

If you see a woman weeping at a tomb or plinth, this is considered to be the mourning ‘widow’ / ‘grieving woman’ / representation of the Madonna. The woman was the focal point of the family and considered to uphold the virtue of the house, hence why the focus of mourning has been centred on the matriarch. So, considering the woman to be a ‘widow’ is somewhat incorrect (as often many say she is the ‘weeping widow’), as a mother or female relative or friend may wear a piece depicting an idealised woman for a person other than a husband. So, would a female wearing a mourning woman be wearing an interpretation of her literal self? For the purpose of this little overview, we won’t consider the literal matriarchal paradigm throughout the 16th to 19th centuries that I would generally cover of the woman and considering that we’re only looking at the woman for the brief window of Neoclassical depictions, the woman is the Neoclassical ideal and should be considered as such. But is that ideal simply ‘grief’? Let’s take a look at some variations and what to do when in doubt.

If the woman is pointing upwards, it is a sign of faith and hope of the heavenly passage, also denoting that the soul of the loved one has departed.

If you see her hanging onto a cross, this is faith and fidelity. This can be seen in the “Rock of Ages”, written in 1763 by the Reverend Augustus Montague Toplady;

Nothing in my hand I bring,

Simply to thy Cross I cling;

Naked, come to thee for dress;

Helpless, look to thee for grace;

Foul, I to the fountain fly;

Wash me, Saviour, or I die.

The imagery is quite self explanatory and the depiction described is found more in funeralia, unless the woman is clinging to a pillar or anchor, which is more common in mourning miniatures and blends its symbolism with the direct sentiment of grief, fidelity and eternal love in the woman and inserts the symbol that she is interacting with. For example, consider that the woman is the primary/personal symbol for the mourning or sentimental piece and then look at how she is interacting with the symbols around her (secondary symbols). Is she sitting, looking at cherubs take the soul of a child off to heaven? Is she leaning or draped over an urn or tomb? Is she standing with her head turned, holding an anchor? Note the secondary symbols here and how they can represent a child, parent, husband, friend or simply the essence of an emotional allegory or sentiment. Here, she is the ideal symbol of the person and may not simply be grief itself, but the wearer can relate to her, regardless of gender.

One must also analyse the look upon the woman’s face to pay attention to her demeanour; is she crying, sad, stoic? Is she standing, sitting, looking up? Is there more than one woman on display? Many pieces were pre-designed and simply customised in the 18th century, whereas others were created originally at the prerogative of the person who had it commissioned, so the woman can often be quite naively painted or she can be one of the most detailed figures in a miniature. This is a testament to the importance of the figure in Neoclassical mourning pieces. Perhaps the woman (or women) depicted are part of a religious allegory (be it Greek, Roman or having Christian allusions), beyond the simple interpretation of the Madonna. Of course, depending on region, much of the Neoclassical symbolism was represented in different manners.

Throughout the Continent, you have a greater influx of Roman Catholic, Eastern/Oriental Orthodoxies and Protestant influences that didn’t have the more isolated Anglican control of Britain, hence the is a lot more movement for interpretation of the woman as depicted. She is a motif that has been interpreted in other ways by other cultures dating back to pre-history. From the nature that the woman is the one who bore us, the sign of fertility and as a focal point from where life springs from, her interpretation must always be considered first. Look to the depiction, note its point of origin (French, English, American, perhaps an Italian cameo) and begin interpretation of her based upon cultural relevance. This can push aside basic notions of her simply there for the purpose of mourning and shed an entirely new light upon what the woman is doing in the scene.

An example of this is perfectly captured in this French ring. On first look, the ring’s depiction is unlike the basic grieving figure that we take for granted. Simply considering this as such defies the very nature of the piece. What we can make of it, however, is she has two phrases written on her dress; upon the collar is “Longe et Prope” (far and near), and on her hem, the phrase “Mors et Vita”. Upon her head, she is crowned with myrtle (like friendship, evergreen) and pomegranate flowers (concord and internal union) and she is also barefoot (for friendship knows no inconvenience too great for it). Next to her is an elm tree, depicted dead/lifeless symbolising that one true friend does not abandon another in distress, and true friendship is based on mutual support and interdependence. As to the scene itself,

A woman bares her breast (her heart is open) where the phrase “Longe et Prope” is, because for true friends, there is no difference no matter how far the distance or how much is changed by time and fortune. Also, a friend is always prepared to live and die for the sake of friendship. – Iconography – Historical Development, Cesare Ripa, 1593

This piece reflects upon a literal representation of the woman and in this case, its intent is more of a portrait with the intent of grief, rather than the idealised ‘symbol’ of grief. Whereas, the piece shown here is an idealised symbol that can be represented for both men and women.

Willow

As a device for mourning use, the willow is the perfect representation of grief in a symbol. The way it perpetually hangs downwards is ideal for the artist to use it as a way of setting the mourning scene and also excellent for hanging above the urn/plinth/female to express sadness.

In this miniature, we can see the willow in that usage; it heavily hangs over the the scene, but it is much more highly detailed than earlier pieces would be. The shading in the colour show the light source as being from the top right corner of the miniature and the trunk reflects this, with a lighter shade of brown being used to the right. It was built in several layers of paint, as the base undercoat interacts with the sky and show the leaves of the tree. This is nothing more than a simple addition of light brown, but with the use of the dashes as the leaves, this piece comes to life in heavy detail. It resonates with the eye, as the simplest of shapes makes the most complex detail that the tree can convey.

From its history, the willow took to prominence from the post 1765 Neoclassical movement, but dwindled after 1820. It was found in all kinds of jewellery and re-appropriated in jewels through the 19th century, but never reaching the prominence that it had.

Cypress

Known as the ‘mournful tree’ by the Greeks and the Romans, the tree was sacred to the Fates and Furies as well as the rulers of the underworld. The tree would be planted by a grave, in front of the house or vestibule as a warning against outsiders entering a place corrupted by a dead body. Romans would carry branches of cypress as a sign of respect and bodies of the respected were placed upon cypress branches previous to interment. It is such for reasons as this that the tree still survives in the Muslim world and in Western culture, the cypress designates hope, as the tree points to the heavens. Here, there is a great continuity of usage for the tree, as despite its cultural interchange, it still remains understood for the same purposes in death.

It is the usage for its heavenly motif that we focus on for jewellery in the Neoclassical era, as the period of around 1760 is when the symbol came into regular mourning depictions, painted on ivory or vellum. The cypress is mostly shown in the background to the willow in the foreground of a mourning depiction, as the mourning woman would often interact with an urn, tomb or willow, but rarely with the cypress itself. Due to is constant usage in cemeteries and reflecting the classical usage of planting a cypress upon death, the cypress is still most commonly seen at the graveyard and the mourning depictions of the tomb or urn on plinth are reflective of that. The cypress’ seen flank the cemetery as they would in reality. Other depictions of the cypress may be the lonely cypress on a rocky outcrop or a singular cypress surrounded by other mourning symbols.

By the 19th century, the cypress was depicted in leaves and branches on jewellery, rather than the full sized depiction. In this way, it could be utilised with other symbols as the Neoclassical concept of depicting full mourning scenes had given way to more specialised and smaller depictions of individual symbols to convey a meaning.

Urn

Note the detail to the urn on this piece; the embellishment to the drapery and the base are quite elaborate for a depiction made up of simple brush strokes. The history of the urn and its usage in jewellery is essential to understand why it was such a prominent focal point in Neoclassical jewels.

The urn itself is a vessel, or more specifically a vase, which naturally have their beginnings in pre-history when humanity began gathering items in order to carry them. We won’t be dwelling on this form of history, but rather the ancient Greek use of the urn in artistic depictions. The urn itself had evolved as a decorative item, often with art displayed upon the vessel itself prior to Greece in neighbouring Mediterranean societies, but its interpretation in jewellery design stems mostly from the Greek and Roman scenes in art and their reinvention during the Neoclassical period.

Usage of the urn had never wavered, however. Cremation of the body and the collection of ashes in the urn is a method that survived ancient civilisations well into the Dark Ages. The name itself is derived from the Latin ‘uro’, meaning ‘to burn’, so no matter what the shape of the vessel the title was always ‘urn’. This is a concept that never left the mainstream mind and its uptake as a Neoclassical symbol and its consistency as a funerary motif is simply a natural evolution for the urn’s depictions.

While burial became the more popular method of interment, the urn still retained its status as a symbol of death, testifying the death/decay of the body and into dust and the departed spirit resting with god.

This brings us to the draped urn. I’ve written about drapery in a previous Symbolism Sunday, but here we’ll focus on its most important use in relation to the urn. The draped urn itself often denotes the death of an older person, however, the drapery is often a constant when in relation to death. Interpretations of this can be when the shroud drapery denotes the departure of the soul towards heaven in relation to the shroud over the body, the drape is the partition between life and death or that it is guarding the sacred contents of the urn itself. In jewellery, finding the urn draped or undraped is quite common, but why is it so?

As hinted at before, the urn is a motif that reached incredible heights of popularity in Neoclassicism due to its interpretation from the original classical depictions. It was a motif that was easily lifted from its source and fulfilled all the classical resonance that a revival period needed to convey the style of its respective era. With the focus back upon the personal nature of mourning and the departure of the direct link towards god, death itself became something worn prominently in mainstream fashion. The urn was a perfect way to show this, draped or undraped. Sitting on top of a plinth, column or tomb, the urn is often the central focus of the mourning depiction. The mourning character in the depiction (male or female) is often interacting with the urn in some way, either leaning against it weeping, sitting near it, standing beside it or looking at it directly. This links the personal nature of mourning from the person into the jewel itself. The mourner is the wearer or the person who created the dedication and the urn represents the loved one. Consider that; there’s a direct link in methodology of the urn to the self, this is why the urn is the central motif and not the mourner.

Consider that when looking at a brooch, ring, bracelet clasp, pendant or any other peripheral from the late 18th to early 19th centuries. The urn is the concept that should draw the eye and take precedence over everything else.

Yet, it is a symbol that disappeared soon after the first quarter 19th century. If you’ve read anything else on this blog, you’ll know that the Gothic Revival period played a key role in reverting society back to more ‘traditional’ values and using a direct relation to the body in the urn conflicts with the burial/god connection which was part of the social understanding of life and death, that Christian values returned to a life under god. You can find the urn in use to around the 1820s, but many of the latter uses in jewels are anachronistic in the same way that memento mori would have been during the late 18th century. However, in funerary, the urn was still retained and is to this very day. In fact, its use in architecture in the latter 19th century / early 20th century was quite typical, but it had largely disappeared as a motif to represent the self in mourning.

Plinth

The column and plinth are two of the most important secondary mourning symbols of the Neoclassical period. These symbols are the basis of the mourning vessel (urn), which often show the customised sentiment which was often chosen by the person who commissioned or purchased the jewel.

The column represents the strength of life, as it points towards the heavens and is usually (next to the image of a weeping woman) one of the most prominent symbols in a memorial / sentimental scene. So, you have this strong, proud object, seemingly timeless (eternity) and often there is a broken variation. That leads one to think that the life has been cut short early. And there you have it. Involved with this is also grief, decay and the concept of this strong central figure being broken can represent the loss of the patriarch / matriarch of the family.

Hair

Evolution of hairwork over the 18th century was rapid and on a large scale. Jewellery changed with fashion, as the two are intrinsically linked. Smaller styles of jewellery that had grown with the 17th century began to disappear and by around 1760, and new, larger forms became the standard. Hairwork over this time was becoming more affordable and a craft which ladies could do at home (though not to the extent of the 19th century). A letter from the Duchess of Portland to Miss Catherine Collingwood, written on December 1st 1735, suggests that ladies were in the habit of working the hair, leading the goldsmiths to provide the gold settings 4. Pieces made to order became more and more popular in the first half of the 18th century, with lockets (especially in the popular heart motif) containing hair becoming increasingly common. As larger jewellery with glass replaced faceted crystal, simple weaves of hair could be placed underneath, without it being a speciality craft or as expensive.

By the 1760s, hair was reintroduced in mass produced memorial medallions and lockets (in England and on the Continent), as it was mixed in with sepia and painted on to ivory. Sepia / hair painting is a typical and very popular method from the 1760s to around 1810, with many pieces being a standard style (sometimes chosen from a hairworker’s catalogue) and tailored to the individual with the appropriate name and inscription. Chopped hair also was a common feature of memorial art on ivory (sometimes vellum), with scenes / symbolism assembled with hair and glue. Hair weaving was also in high demand, with everything from brooches to miniatures holding a compartment in which to place the woven hair. Hair weaving was becoming far more intricate, with hair being entwined with pearls and gold.

Combined

As a jewel of presentation, this would be a miniature that could be displayed in the home and travelled with inside a dedicated case. While the earlier styles were worn at the neck, the heavier these miniatures became, the more they were displayed in a way a photograph would be today. Photography was the death-knell for the miniature, allowing people to attain affordable keepsakes of their loved ones (even post-mortem), but the artistry that was developed in the British miniaturist schools was lost; leaving behind a resonant emotion in allegory that the simple fact of a photograph couldn’t replicate.

In this jewel, we see the last elements of the style, depicted in a way of the individual weeping at the urn. Instantly memorable for its mourning attributes, the style of this miniature resonates as it underlines many of the mourning symbols that are still in use today.

In its final moments, this miniature was made for a family and to be acknowledged as such. Mourning jewels are part of time itself; once adapted, their meaning is morphed and lost, but with such a deep and profound vision, this jewel will carry its message of sadness well into the future.