Symbolism, Mizpah

Let’s get all along the watchtower for today’s Symbolism Sunday! It does indeed look like such a lovely day outside, perhaps it would be best to grab a blintz or a bagel (why not both?) and find a comfortable seat. It’s days like this that we never should be absent, but if we were, I’m sure the LORD would be looking down on both of us.

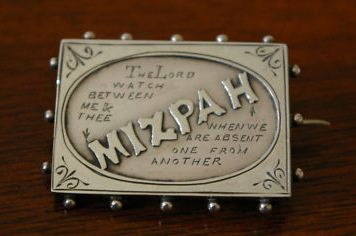

That was certainly long winded and I am in no way apologising for it. Why? Because it’s Symbolism Sunday and we’re going to delve into one of the most widely used dedications/sentiments/motifs in 19th century jewellery – Mizpah!

Mizpah is a concept that was grasped upon during the second half of the 19th century, and with most 19th century concepts and allusions, we carry them with us today, though perhaps not as strongly as it had been then. The jewellery produced around this Mizpah concept varies widely and fits so well into the 19th century paradigm of gift giving. It also fits perfectly into the romantic allusions of the time, as opposed to the far pre flagrant values of the Neoclassical era. By the time of the late Victorians, Western Society had changed dramatically, the concepts of physical borders and cultural territory had bent towards empire building and the world had become a global entity, run by heavy machinery and mass production. This is so important to establish before we look into why jewels and tokens like Mizpah became so popular, without the context, the symbol itself is relegated to its bare minimal symbolism and that’s too narrow a concept when such a popular motif underpinned so much. The motif is still produced today, more as a curiosity than it had been as a raw sentiment, having a resurgence in World War I (a time when mourning and sentimental jewels fell from favour) and still produced regionally as a token of affection.

From this, we have to consider that the modern mindset and culture is vastly different than what it had been in the 19th century. The values and social implications of what we see around us in advertising and even how we interact with our co-workers and family would be devastating to Western cultural social standards. To overtly display lurid affection would do yourself a discredit and if you had a family association, they too would suffer for those indiscretions. Hence, a concept such as Mizpah (which we will get to in a minute) held a level of gravity between lovers. While it is seemingly safe by today’s standards, the depth with which it would be given held a very loving sentiment.

Let’s look at the dedication itself. To do this, we need to go an analyse Genesis 31:49:

And Mizpah; for he said, The LORD watch between me and thee, when we are absent one from another.

Mizpah itself is literally a ‘watch tower’ or ‘lookout’. There are several Mizpahs in ancient Israel and this brings the dedication into more context. As we develop this understanding, we’ll look at how the dedication developed other meanings as it went along. From a basic standpoint, the ‘LORD watch between me and thee, when we are absent from one another’ is the most fundamental point of this bible verse. Simply that the fungible nature of love is transformed by the Lord as it is conducted through Him, making the love pure, holy, honest and completely with virtue. Between us, the Lord will watch when we are absent, as opposed to looking up at the stars and knowing your loved one is looking at the exact same stars, or that your heart is so full of love, your loved one will feel it no matter where they are. It’s also a dedication of safety. It denotes that the loved one, if on holiday, war, off to work, will be under watch and protection of the Lord. That the dangers of the world will be prevented from affecting the loved one, the token itself becomes a token of protection, as much as one of love.

Let’s look at the passages themselves in context:

44 Now therefore come thou, let us make a covenant, I and thou; and let it be for a witness between me and thee.

45 And Jacob took a stone, and set it up [for] a pillar.

46 And Jacob said unto his brethren, Gather stones; and they took stones, and made an heap: and they did eat there upon the heap.

47 And Laban called it Jegarsahadutha: but Jacob called it Galeed.

48 And Laban said, This heap [is] a witness between me and thee this day. Therefore was the name of it called Galeed;

49And Mizpah; for he said, The LORD watch between me and thee, when we are absent one from another.

50 If thou shalt afflict my daughters, or if thou shalt take [other] wives beside my daughters, no man [is] with us; see, God [is] witness betwixt me and thee.

51 And Laban said to Jacob, Behold this heap, and behold [this] pillar, which I have cast betwixt me and thee;

52 This heap [be] witness, and [this] pillar [be] witness, that I will not pass over this heap to thee, and that thou shalt not pass over this heap and this pillar unto me, for harm.

53 The God of Abraham, and the God of Nahor, the God of their father, judge betwixt us. And Jacob sware by the fear of his father Isaac.

54 Then Jacob offered sacrifice upon the mount, and called his brethren to eat bread: and they did eat bread, and tarried all night in the mount.

55 And early in the morning Laban rose up, and kissed his sons and his daughters, and blessed them: and Laban departed, and returned unto his place.

Here, Mizpah is a covenant and a warning. It’s underlying concept is that of love and protection, however; protection for Laban’s daughters and protection against harm. Jacob and Laban sealed this with sacrifice and the sentiment begins. There is a much larger concept to take into account here, especially when we think of how the Mizpah tokens were given and received. Mizpah, while often thought of as being simply their basic love/protection context show a far greater resonance in terms of the pact made between giver and bearer of the token. There is almost a threat involved if the pact is ever broken by the two, bolstering the sentiment of love. That two people could enter into such an agreement is fundamentally profound for two lovers to enter into.

We’ve seen why this pact is so profound and fundamental, but why so necessary? As previously mentioned, there was the great impact of high mortality, large scale war, empire and mass transit/communications/production. From a simply production standpoint, Mizpah were wonderful tokens of gift giving, but the necessity of having to give them, particularly in the second half of the 19th century is so important. During this time, we have to consider that in 1876, Queen Victoria was crowned Empress of India and that the sun never set upon the British Empire. To get to this level of distinction, many lives were lost and much conflict was to be had. Traditional kingdoms were branching out across the world to claim their own empire (French Colonial, German), causing a massive shift in the established cultures where they were encroaching upon. Even the Americans were fighting with Mexico/Civil War/Spanish – it seemed as if there was no part of the planet free of conflict.

Chances were that if a loved one was going to war, the methods of fighting were still based in infantry and there was a good chance they would not return. Therefore, this tiny little charm becomes so incredibly necessary for the memory and love. It may be the most profound token of affection that one could give. Its loaded symbolism of protection and love spoke volumes when given during this time. This is also a reason why so many pieces spread out through the world.

Reversely, a solider may buy a colonial piece abroad, as there was no level or quality with the Mizpah pieces. Base metals or precious metals, with stones or without; it didn’t matter, they could be purchased from the source and taken back, the sentiment was always the same. This continued into World War I for exactly the same reasons.

That really shows why Mizpah was so essential in the 19th century and how it got so popular. The sentiment, the protection, the culture and the society were all perfectly suited towards each other.

How could/can these pieces be seen? Brooches, rings and inscribed in lockets are the most ubiquitous. Yet, they are on virtually every form of jewellery peripheral and as stated, vary wildly in quality. You can find the earlier pieces around the mid-19th century, right at the end of the height of the Gothic Revival and directly in the centre of the Romantic movement. Look for pieces to be hallmarked, though there are production lines today which put fake stamps inside to emulate the 19th century pieces and garner high value. It’s often hard to tell, as the production values are almost identical, however, look for signs of wear and age.

Use with other symbols is also important to note. The message itself is such a strong one that it often is the primary symbol, however, you will often find it balanced with one or two hearts (denoting the lovers, if the hearts are separated, then there is the distance shown). It is not uncommon to find the full Genesis verse balanced with the Mizpah (either on the reverse or on the right of a brooch), shown with an arrow intersecting the Mizpah text, joined with a laurel, forget-me-not, horseshoe, scroll, oak, acorn, dove, branch, painted in enamel or just about any of the hundreds of Victorian symbols for love, affection and memory. The more curious of the Mizpah pieces, at least for me, are the ones that do adapt to the changing art styles. Those that break free from the rigid Victorian revival art styles and Romantic symbolism and take on Art Nouveau, Art Deco and more modern styles. It is the ability of a motif to adapt that keeps it alive.

And so I say to you Mizpah! Keep safe, keep well and don’t forget to feel some affection on this lovely day.