Vulcanite

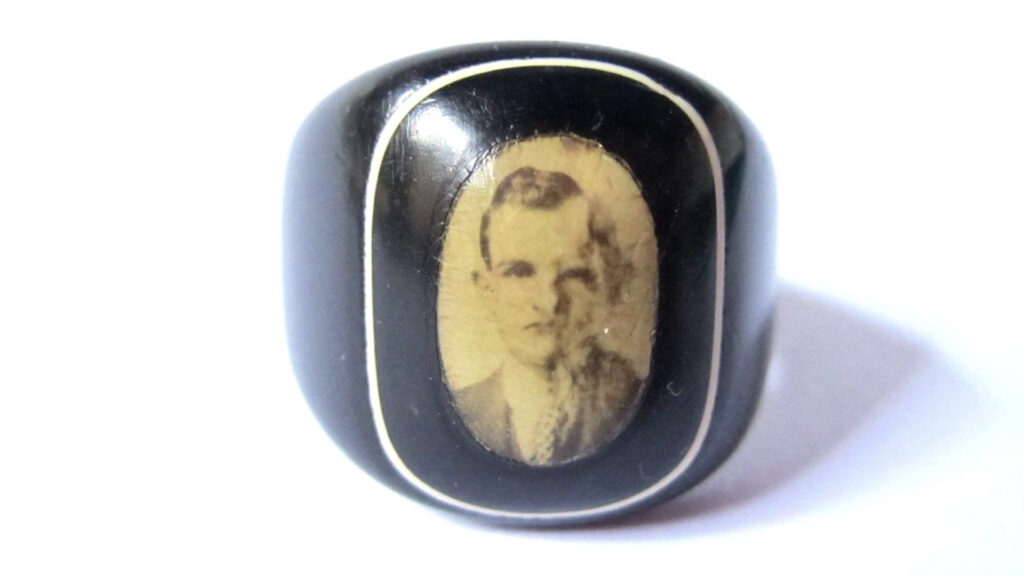

Vulcanite was patented in 1846 by Goodyear (the same tyre manufacturer of today), as the patent specified a manner of mixing rubber and sulphur, then heating the mixture to one hundred and fifteen degrees Celsius. It produces a brown powder when scratched and has a faint odour of sulphur. Often, a vulcanite piece in good condition can be hard to discern from actual jet, but one of the signs to look for (next to burning it with a needle and checking for the smell – Jet smells of coal) is to look at the design and note if the piece is obviously moulded (such as the smooth, curved expanding band on this piece) or if there are the obvious carving marks.

Often called ‘ebonite’, vulcanite was the most mass-produced rival to actual jet. Its ability to be moulded and not carved, along with a relatively low cost vs. labour to manufacture made vulcanite a material that was accessible to middle and lower classes of the 19th century, especially at a time when actual jet was the height of fashion. However, vulcanite, like other plastics has been seen to devalue the real thing.

Vulcanite could withstand high polishing and show a high gloss lustre in the same way as jet, but over time, the fading to khaki from black is a tell-tale sign. Vulcanite has a relatively low tolerance to sunlight so, finding pieces in their original condition isn’t hard (as there were many thousands of pieces produced), but it is becoming more difficult.

When buying jet or vulcanite, be vary wary and scrutinise your piece closely. One of the easiest ways is to spot the carving behind the memento (photo or hair) in a locket, as this wasn’t smooth and moulded like vulcanite, jet will often show the marks of the carver’s tools.